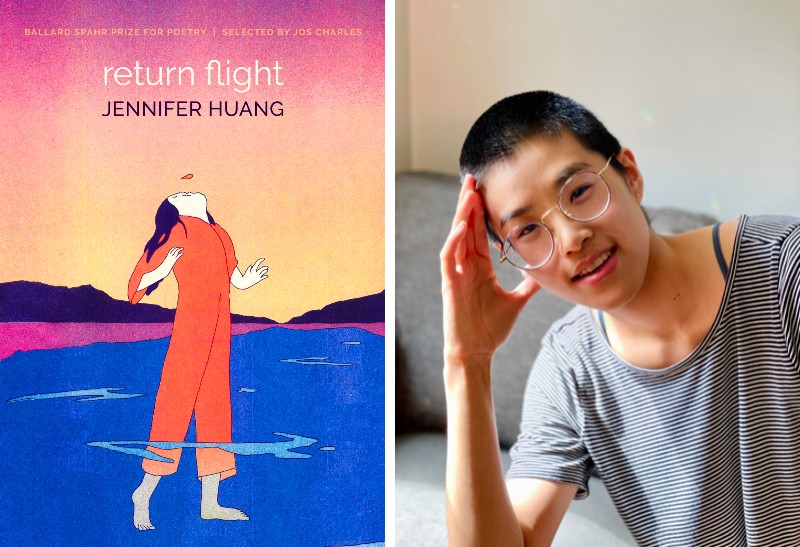

Jennifer Huang reconceptualizes home in their new poetry collection, "Return Flight"

Poems in Jennifer Huang’s Return Flight map the ways that a person can depart and return to themself, though sometimes that self is no longer the same. Huang holds an MFA in poetry from the University of Michigan Helen Zell Writers’ Program, and their collection won the Ballard Spahr Prize for Poetry in 2021 judged by Jos Charles.

Some of Huang’s lines suggest disillusionment, given that “This is not what I imagined.” Other lines show a separation from oneself and the effect of external influence when, “The distance between me and I grew / So you could love me as you’ve / always imagined.”

Return Flight plays with desire and how to get what is wanted and what is the cost.

Another poem, “Departure,” describes a meal at which “We would / choke down our food to get seconds though there was always plenty,” and when faced with delicacies, the father would "tell me, Chew slowly and feel what you are eating.” That advice to process slowly and notice could be extrapolated to a number of situations in these poems.

The search for self continues even as that evolves in Return Flight. The poem “How to Love a Rock” teaches us, “How you / worry now, let it go.” As the self is reclaimed, uncertainty remains when, “Unborrowed from rocks and salt and dirt and root, where I go from / here, I don’t know.” It could be anywhere, which fits with what Huang writes in the acknowledgments: “This collection is, in part, a search for home—and the realization that home is not a destination but a journey.”

Huang was a resident of Michigan and now spends their time in Michigan, Maryland, and other places. I interviewed them about Return Flight.

Q: What led you to write poetry and pursue an MFA?

A: What we read in high school went over my head. But, in college, I was taking a bunch of different classes in creative writing to see if I wanted to major in it—at the time, I was interested in nonfiction—and decided to follow a curiosity I had for poetry. I fell in love with the genre because it seemed to put together my love of words and visual arts.

I decided to apply to MFA programs after about a year and some change working in NYC. I had stopped writing, but the community at Brooklyn Poets got me back to it again. At the time, I was starting to feel burned out, so I knew I needed the time and space, as well as the resources of a university, to do the writing that I wanted to do. It just felt like the next best step to take.

Q: The passage you quoted from your journal about home being “everywhere, yet nowhere” forms the basis of your book. Tell us about writing Return Flight.

A: At first, I was interested in writing about water, the strange experiences I’ve had, and how this element feels very ancestral to me. How water also felt like home; and how water is also what divides me and my family from another home, Taiwan. Soon, these ideas turned into writing about my relationship to “home.” Growing up with immigrant parents and in a family of divorce, I often thought about what “home” means and how I could find and make a home for myself. I wanted to express these questions and yearnings through poems. That’s mainly how Return Flight came to be.

Q: Poems in Return Flight incorporate Taiwanese history, the language, Chinese folk stories, and Taiwanese food. How would you say that you connect your own experiences of Taiwan with your poetry?

A: I connect my own experiences of Taiwan with my poetry by writing about stories I’ve heard and learned over the years. Some of the poems retell these stories with my own spin (“That dawn at the beach”), others are persona poems (“From the Taiwan Cypress in Alishan”), and others explore my own relationship to Taiwan (“Layover”). Through it all, my main goal is to share about the not-so-well-known history of Taiwan—and my own complicated relationship with the country, culture, and history as an outsider who is not really an outsider.

Q: Places from Taiwan to America thread throughout the poems and form a new landscape. The notes section says that “‘Relief’ was written for Silver Lake and Pinckney Recreation Area in Michigan,” which are beloved by many. How do you see place working in this collection?

A: In this collection, place is related to ideas of home, especially homes in which something incredible happens. I really feel that each place that I’ve spent time in has given me lessons and tools that I take with me wherever I go. With “Relief,” in particular, I was writing about a very specific experience of a summer afternoon swim in Silver Lake. I remember coming home to my apartment in Ypsilanti, lying on my couch, and just feeling my whole body buzz. I felt so relieved and good and grateful. I wrote the first draft of this poem right then and there. In that way, I guess place and how it affects me is one of my inspirations.

Q: Pleasure, pain, love, and colors weave throughout these poems, such as “Notes on Orange,” which asks, “What is the true / opposite of human? Maybe orange.” Later in the poem “Manifest,” some lines say, “I listened and thought/ it was fate—I was to have / a life filled with cursed / love.” Do you think that the poems write themselves out of some realities and into new ones?

A: I think so! And if not writing themselves out, then at least creating a space in which a new reality can emerge or be imagined. Imagination is so powerful because, I think, if we are able to see something in our minds, it is much easier to create into the physical world.

Q: The poems include different forms, like haiku and erasure. What draws you to these forms?

A: When I’m writing a poem, I love to pay attention to its aesthetics and how it looks on the page. I think this comes from my background in visual arts. There’s also something about the restriction of form, especially in something like haiku, that makes me more creative. I end up using my brain in a different way and then writing becomes like a puzzle. I think I once heard Jericho Brown explain form—and this is totally from memory, so I might be getting it wrong!—as a way to distract the brain, which allows for something surprising, even more spiritual, to come through. I find that to be true, too.

Q: How did you decide to submit to the Ballard Spahr Prize? What was it like to win?

A: At the time, I was submitting to as many awards as I could. This prize was free to submit, and I love Milkweed Editions, so it felt natural for me to go for it. Winning was, honestly, surreal. When Daniel Slager called to tell me the news, I think I was in shock the whole time!

Q: What’s on your nightstand to read?

A: My pile of nightstand books is so long! Some include Finance for the People by Paco De Leon, The Kissing of Kissing by Hannah Emerson, Bitter by Akwaeke Emezi, Dear Memory by Victoria Chang, and more! I am great at starting books—not so great at finishing them in a timely (whatever that means) manner.

Q: What is on the horizon for you?

A: This is a tough question! Right now: exploring and feeling into what it is like to live in my hometown [Rockville, Maryland] as an adult. I never thought I would be back, but something feels right about it. One thing I’m super looking forward to is growing an experimental vegetable garden at a community plot this summer. Experimental, because it’s my first time growing food!

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.