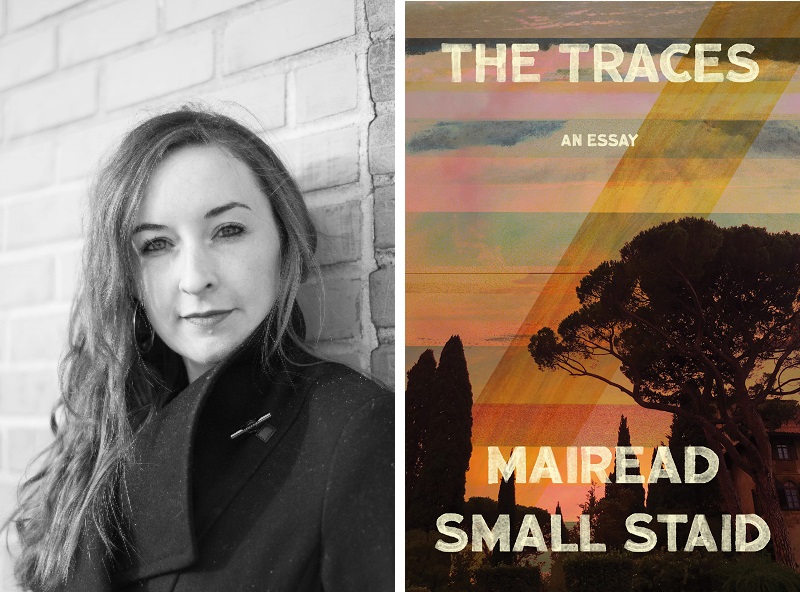

Author and Former Literati Bookseller Mairead Small Staid Narrates Travels in Italy and the Search for Happiness in Her Book of Essays, “The Traces”

Happiness may be elusive, but the quest is part of the experience.

“Happiness is the endpoint and the race itself, the finished vessel and its firing,” writes Mairead Small Staid, an author, librarian, a University of Michigan alum, and former Literati bookseller.

Her new nonfiction book, The Traces: An Essay, recounts the author’s time in Italy, studies the concept and feeling of happiness, and critiques art and literature. Staid’s chapters form individual essays that roam through concepts such as whether a person is different when in different places and look at sculptures and paintings by artists such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. Italo Calvino’s novel, Invisible Cities, is a focal point to which the book repeatedly circles back.

The exploration itself brings novelty and thus pleasure. Staid writes that, “Here lies another possible explanation for my happiness, this sustained and sustaining newness: it’s November, after all, and still each ordinary day—each breakfast, each cigarette—is tinged with cinematic light.” The fresh sights and circumstances can reinvigorate one’s outlook.

Staid finds that dwelling on the past may not be the path to happiness because time moves “only forward.” Words and memories become imprecise means to recall those happy times, yet they are necessary for some connection to a treasured, earlier time:

We travel, talk, eat, drink, read, laugh, and think, and then—in that same instant, often—we write that thinking down. That traveling, that laughing. Such writing is an act of math, in my mind, adding another dimension to the figure formed by the scene: think of a line fragment hidden behind a point, a cube rising from a sketched square. This geometry functions as archaeology, preserving not only the added dimension but the others, not only what is written but what inspired it—preserving the moment experienced both within and without as if in a safe, its code clearly written but decipherable only by its author.

The act of preservation creates a new, individual thread tying someone to their remembered scene.

Perhaps (to use a word that the author expresses appreciation for) what makes happiness more distinct is the lack of it. Depression haunts the author, though the season in Italy becomes a bright spot amidst its valleys. The question of happiness lingers, even though Staid plumbs its depths for answers. She still asks:

How to live: my question might be this plain, as old as Montaigne, as Aristotle, as the nameless ranks that came before. Or a variant thereof: How to be happy? How to stay happy? How to bring back a happiness, found and lost? How to stave off a darkness that loiters and returns, that I can’t seem to lock in one place and leave behind? How can my mind move quickly enough to escape—like one of Leonardo’s scribbled machines, powered by its own motion—when my body is confined to one city, one season at a time? Can happiness ever linger, lengthening from action to place, somewhere to be lived in instead of sought? Where is that place? Where is it? And when?

Staid’s answer is clear, though also tenuous: happiness is apparent when found.

Staid earned her Master of Fine Arts from the Helen Zell Writers Program at the University of Michigan and currently lives in Minnesota. I interviewed Staid about The Traces.

Q: When were you in Ann Arbor? What brought you there and what took you elsewhere?

A: I moved to Ann Arbor in 2012 to attend the graduate creative writing program at U-M, and I left—with great sorrow—in 2017, when I received a generous writing fellowship that required me to move to New Hampshire for the year.

Q: The “Acknowledgements” section of your new book, The Traces, mentions that you started the book while working at Literati Bookstore. Tell us more about how you started writing this book.

A: For a couple of years, as I finished my MFA and began working at Literati, I’d periodically push around a bunch of words that I thought might become an essay about the Italian writer Cesare Pavese, suicide, and a semester I’d spent in Florence when I was 20. (I’ve written a bit more about what I thought that essay would be here.) The thing never seemed to work; I kept picking it up and putting it aside, writing and finishing about a dozen other essays while this one refused to cohere. It took me a long time—longer than it should have, probably—to realize that what I was writing (or, not-writing) wasn’t a brief essay but a book. The horror! I’d never done such a thing before; I didn’t know where to start—so it’s lucky that I already had, without knowing it.

Q: The book has a number of chapters, all with the word “cities” in their titles and threads that flow throughout the essays. Do you think of the chapters as individual essays or sections of one large essay, and why?

A: The chapter titles are borrowed from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, which serves as my book’s spine and interlocutor and patron saint. Though each chapter takes on a particular city (Florence, Rome, Venice, etc.), writer (Dante, Aristotle, Montaigne, etc.), and subject (architecture, cartography, physics, etc.), I do think the chapters have to be read as parts of a single work—I’m not sure they succeed as stand-alone essays. I conceived of the book as a whole and wrote the chapters in the order they appear; the topics assigned to each gave me a way to silo and organize material, but the thoughts and quotes and scenes of one chapter inevitably started chatting up those of the next, spilling over and intermingling, as thoughts tend to.

Q: How did you first decide to read Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino? What compelled you to incorporate it—and the other authors and artists whom you quote—into your own book?

A: I can’t remember why or when I first read Invisible Cities; it was years before I started writing The Traces. But when I began trying to piece the book together, I was overwhelmed by the prospect of working, for the first time, at such length; I needed a structure that could contain the many, occasionally tenuous connections I wanted to make. Stealing from Calvino’s hyper-structured book gave me a way of sorting and ordering things, while his characters are engaged with many of the same questions that preoccupied me: travel, memory, desire.

As for the million other authors and artists quoted, I can’t help it. An agent who read (and did not represent) the manuscript said she wanted more “me” in it, and I know what she meant—more memoir, less riffing and criticism—but I also can’t fathom it. Am I not a line I love by Anne Carson? Am I not Michelangelo’s Rondanini Pietà?

Q: The Traces begins with the author missing a city. Desire, the self, and place are wrapped up with happiness, but saying that one or more of them being out of joint is what leads to unhappiness is not necessarily accurate either. Did writing this book change how you thought of Florence and Italy? Why or why not?

A: Oh, that’s an interesting question. My love for the place and my nostalgia for my time there is undimmed, I think, and writing about Italy was simply a way of applying a kind of varnish to that nostalgia, crystallizing memory into language. There’s loss in that process, certainly, but there’s also a sense of satisfaction, of pinning down something that had long eluded me. That doesn’t mean I’m rid of it—in Still No Word from You, Peter Orner says, “It isn’t true that we write stuff out of us,” a sentence I love. Florence, those months, those moments—they still carry an outsized weight in the story I tell myself about myself. But it’s fair to say I don’t feel the ache for that time or place quite as keenly as I once did. I’m a scavenger, always taking what I can from an experience and trying to turn it into writing, and after many years, I finally managed to do that with Italy—what else could the country possibly have to offer? (Joking, of course.)

Q: Early on, you write that, “This is how time works, a series of selves stitched together.” Could writing this book have added another self or more selves to the collection?

A: A mirror self, a forged self, a self as made-up as any other—yeah, absolutely. In the essay “Levels in Fiction,” Calvino says, “The preliminary condition of any work of literature is that the person who is writing has to invent that first character, who is the author of the work,” and I think this is just as true of nonfiction.

Q: You had spent time in the places you write about, and you write about how memories can evolve. Did you travel to them again to write this book, or did you write from memory? How did writing the book alter your memories?

A: I didn’t go back to Italy while writing the book, and I haven’t since. (I would love to! If any benefactor reading this would like to send me on assignment, by all means.) I wrote from memory, with the help of a notebook I kept at the time. It’s hard to know how my memories have been altered, stuck with their current iteration as I am, but my amateur’s understanding of the latest in neuroscience is that every time we revisit a memory, we reinforce our perception of it, polishing up the version we’ve come to believe in like a gem. Writing was a very intensive kind of revisiting, so my memories—the ones described in the book, at least—are fairly gleaming at this point, unbreakable, finished. I do think there’s something devastating in that.

Q: I am also a librarian! You describe a library in which you worked in The Traces. How does your work as a librarian interact with your writing and being an author?

A: Working at a public library is nothing like I expected, coming from a bookselling background, and very rewarding: I have all sorts of idealistic thoughts about the library as an institution, and those ideals are both eviscerated and upheld on a daily basis. (You know what I mean?) My work as a librarian feels fairly separate from my writing life, to be honest, but it does keep me well-stocked in the piles and piles of books I need to keep my brain whirring away, wanting to make books of my own.

Q: What is on your pile to read?

A: I’m writing just a couple days before the release of a newly translated collection of Calvino’s nonfiction, The Written World and the Unwritten World, so I’m very much looking forward to that. Also in the pile is Anahid Nersessian’s Keats’s Odes: A Lover’s Discourse, John Felstiner’s biography of the poet Paul Celan, and some books by the Moroccan scholar Abdelfattah Kilito (The Tongue of Adam, Thou Shalt Not Speak My Language), which I love and am rereading for a project. (See the next question!)

Q: On finishing The Traces, I wanted to read it again! What are you working on next?

A: Thank you! That’s very kind. I’m working on a book about translation and marriage, and the ways we speak of each in terms of faithfulness. So far, it’s populated by St. Jerome, Simone Weil, the Bible, the Odyssey, Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, the landscapes of California and Armenia, some ancient buildings, some works of art. It’s a mess. I’m quite excited about it.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.