"'I have a crisis for you': Women Artists of Ukraine Respond to War" acts as an archive of witness and response

"I have a crisis for you": Women Artists of Ukraine Respond to War was first shown at the University of Michigan's Lane Hall Exhibit Space last August 25 through December 16, and it was brought to U-M's Weiser Hall from January 3 through February 23.

And the curators don't think the exhibition is complete.

“I can’t say it's a finished project, because it will have afterlives,” said co-curator Jessica Zychowicz, director of the U.S. Fulbright Program in Ukraine, who also earned her Ph.D. from U-M.

She and co-curator Grace Mahoney—a Ph.D. candidate in Slavic languages and literatures, and a graduate fellow for exhibits at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at U-M—hope the multimedia exhibit keeps finding new venues beyond Ann Arbor and can serve as an educational tool, or at least serve as an archive of work in which women describe and respond to their own particular experiences of war.

"I have a crisis for you" features paintings, writing, photos, and more by:

- visual artist and sculptor Kinder Album

- photographer J.T. Blatty

- visual artist and U-M grad student Oksana Briukhovetska

- visual artist and designer Sonya Hukaylo

- filmmaker, artist, and performer Oksana Kazmina

- visual artist Lesia Kulchynska

- poet and translator Svetlana Lavochkina

- visual artist Kateryna Lisovenko

- poet and screenwriter Lyuba Yakimchuk

Zychowicz and Mahoney did their curation remotely: Mahoney from Ann Arbor; Zychowicz from Warsaw, Poland, where she moved from Kyiv when the invasion began. To inform the project, the curators drew on previous relationships they had with the artists and writers as well as their own scholarship: Zychowicz is the author of Superfluous Women: Art, Feminism, and Revolution in Twenty-First Century Ukraine, and Mahoney is the series editor of Lost Horse Press' Contemporary Ukrainian Poetry Series.

Zychowicz and Mahoney recently talked with me over Zoom to discuss the exhibit. Our conversation was edited for clarity and length.

Q: Could you start by describing the genesis of the exhibit?

Jessica Zychowicz (JZ): Curating this exhibition was very possible for us because we already had established a working relationship, deep knowledge of the field, and we were able to do it virtually. It was difficult for us to think, “Who not to select?”—because there is just so much talent in Ukraine right now, especially around the war emerging.

Grace Mahoney (GM): Certainly, when we started talking about this exhibit, we thought, “Well, is it possible the war will be over by the time it goes up?” And we knew that all the art we were selecting, putting on the walls, and all the poems—there weren’t any conclusions and we didn’t want to draw any. We really just wanted to offer up these images and voices. Many of the artists we reached out to we knew had been already working on the topic of war—because the war started in 2014, after the Euromaidan Revolution.

JZ: Something about the format of showing this exhibit in a public university and taking away the question of a gallery, or collectors, or money—large sums of money—influencing the art was quite freeing for us and for the artists. Because the artists that we worked with are researchers themselves working on questions of violence and the image. And they, I think, were very motivated by the opportunity to engage with communities of knowledge, and other researchers, and to impact students. In curating, we really worked to make this exhibit powerful but also easy to replicate without spending a lot of money, so that other public institutions may be able to use this as an educational tool to get conversations about gender, violence, and war going in the future. We wanted to make this very user-friendly for the hosting institutions.

Q: What was your process for putting the exhibit together?

GM: Knowing that we had a student audience, and that this was also going to be located in a workspace where people go on a daily basis—not a gallery space that’s separate, that you go to knowing you’re going to see certain images, encounter certain themes—we wanted to be sensitive to that. Even though there are still very powerful and emotional pieces, we [refrained] from using a lot of pieces that had really graphic violence or involved really sensitive topics, like rape—which is very valid in a discussion of this war, especially in terms of gender and gender-based violence. But being sensitive to that—and that those subjects are very triggering—we were keeping that in mind as we selected pieces to exhibit.

JZ: Photography, especially taken in the context of the war—as a kind of document—has a very powerful effect on people. We had a long discussion about whether or not we should show a photograph with a dead body in it. This discussion also has a much wider history in the theory of photography and media, and in our exhibit, we didn’t really have the tools or the proper context to stage that discussion. I think that these are really valuable conversations—and I think we would need a bigger frame to really dig into the theoretical and critical issues of what that is. I hope that those discussions at some point will and can be unfolded out of this exhibit.

Q: Did you commission work for the show, or were you looking for artists who were already responding to the war in their work?

GM: We didn’t commission anything. Some of our artists talk about this in the statements we asked them to write for the exhibit—that even though they hate war, as artists, they are drawn to and [compelled] to work on this topic for a variety of reasons. So there was a wealth of material to draw from and curate. And they also really speak to each other—different pieces from different artists will resonate thematically or aesthetically. It’s really interesting when they’re all in the room together, to see how they talk to each other. Many of our artists had to leave Ukraine and are dealing with that and working through that in their art. These themes are coming up for them over and over again and in different ways. Of course, their artistic expression is always unique, but when I was hanging the exhibit, I could see how—even pieces across the hall from each other—might have some kind of rhyming in their themes and their content.

JZ: I think that it’s the question of identity: “Are you Ukrainian?” This is a question I’ve gotten throughout my career of interviewing Ukrainian women and Polish women and Jewish women—and I don’t like all of these categories, because many people are multiple things, and relations to a nation change a lot. One author I write about in my book extensively is Yevgenia Belorusets—for scheduling and other reasons, she was not able to join this exhibit. But she has been publishing a war diary that’s been translated into English. At the end of that book, she says that whether or not you’re inside Ukraine, and whether or not you consider yourself Ukrainian, you have a right to speak about this war—and you should speak about it. And you should speak about your experience of it, whether it’s as simple as reading the media and having a conversation—the whole world is part of this; the whole world is watching this happen. Some are doing nothing, some are doing a lot. But everyone has a right to speak. And, of course, we put at the center many Ukrainian women’s voices because women tend not to be the number one speaker in Politics with a capital P. But we did want to kind of flip the hierarchy of who gets to speak about war—that it’s not just the Pentagon, it’s also everyday women and their experiences that need to be put at the center.

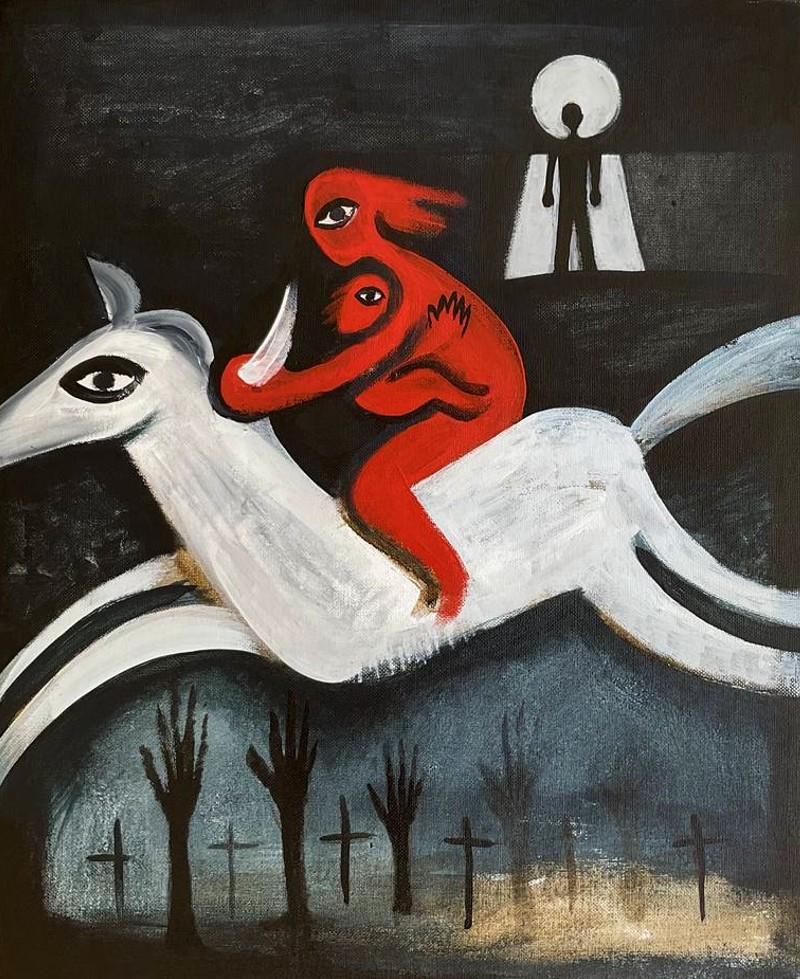

Kateryna Lisovenko, I do not want to live in a world that reproduces collective nameless graves,

I am against it, 2022.

Q: Could you talk about your decision to focus on women artists?

JZ: For me, this was about positioning my work as a form of resistance to the lies and to the propaganda and to the erasing of so much effort and work to build a better society that I’ve been really dedicated to seeing and documenting firsthand.

GM: I just have a strong commitment to promoting women’s work. In my work as a translator and publisher of Ukrainian literature in translation, I make sure that the literature that I translate and publish is bringing more women’s writing into the world—because statistically, women are underrepresented in publishing and in translation. It was certainly not a problem to find really rich art that offered a big spectrum of women’s experiences during this war—from this military perspective that J.T. Blatty can offer us, to perspectives of artists who are thinking about history, to artists who are thinking more affectively about their experiences as family members, as mothers, as wives. There’s a large spectrum there, and [while] I think the media coverage has brought a lot of human stories to us, of course, there’s always a focus on military movements. So bringing civilian and military perspectives together in this space was important as well.

JZ: I’ve talked to some artists in Ukraine now who say they feel guilty, like, “We didn’t do enough to prepare the country for this.” But I think everyone feels that way who has been trying for so long to get the West to revert its attention once more to Ukraine and do something before it got worse—and now there’s no turning back. I mean, the world will never be the same; Ukraine will never be the same as it was. But I think it is important to document every stage of this process—and to not accept any narrative at face value.

Natalia Holtzman is a freelance writer. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Millions, LitHub, the Minneapolis Star Tribune, and elsewhere.

"'I have a crisis for you': Women Artists of Ukraine Respond to War" is on the fifth-floor gallery of Weiser Hall, 500 Church St., Ann Arbor. Building hours are 7 am to 6 pm, Monday through Friday. The exhibit runs through February 23. You can also see the art and read about the artists at the exhibit's companion site here.