Courtney Faye Taylor explores racial injustices and the killing of Latasha Harlins in her debut poetry collection

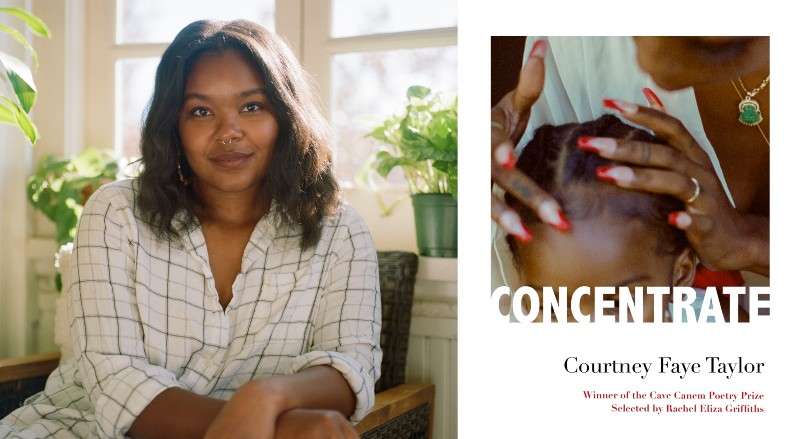

Poetry becomes both memorial and voice in Courtney Faye Taylor's first book, Concentrate, winner of the Cave Canem Poetry Prize. The University of Michigan alum's poems honor, research, bristle, and circle back to the life and killing of Latasha Harlins, a Black girl gunned down by a Korean store owner, Soon Ja Du, in Los Angeles.

“In any black sentence, you’d love nothing more than to had made no mistake.” The opening prose poem that ends with this sentence mourns and fortifies Black womanhood. As Aunt Notrie says in the next poem, “The Talk,” it “Ain’t about trying, it’s about doing.” These lines do not let injustices lie but instead, “The poet wades into an uneasy ocean of interrogations that do not permit her any distance from what she has witnessed her entire life,” writes Rachel Eliza Griffiths in the introduction.

Some of the poems revisit history, like March 16, 1991, when Harlins lost her life. The poet starts another prose poem to outline how:

A timeline details a seriousness of events. As a diagram of occurrence, a timeline’s chief objective is to show how passed happenings caution and contaminate our contemporary sense of momentum. A professor may author timelines to teach what precedes and what follows genocide. On the overhead, Rwanda is a centipede with its head in Belgium and tail on stage of the ’05 Oscars.

The past remains with us as warning and blemish, and Taylor writes, “So I’m drawing a line.”

Other poems fashioned like Yelp reviews make stark the differences in treatment and standards among people. One of them gives two stars for “BLACK OWNED BUT HOURS WRONG ONLINE.” Such an offense garners a bolded complaint and strong consequence that “I will find a Korean store.” The loss of business for incorrect hours reinforces inequity and harshness.

Eventually, the poet goes to Los Angeles and visits the site of Harlin’s murder, “But there are no signs of murder, memorial, or resistance when I arrive. The ground is like any ground. Normalcy devastates. Stillness lies to me about history.” Taylor’s poems teach us that what is not visible is still present.

Early on, Aunt Notrie defines the word "concentrate" as “A strong, hard focus.” Taylor takes on that focus to scrutinize history through the poems. Later, Concentrate is a call to action, as in “Concentrate. We have decisions to make. Fire is that decision to make.” The word “we” leaves no one out. It is all of us who have responsibility.

Taylor is a writer and visual artist who earned her MFA from the University of Michigan, where she won a Hopwood Prize in Poetry. We spoke about Taylor's time in Ann Arbor, her poetry, and Concentrate.

Q: When were you in Ann Arbor, and what was your life here like? What have you been doing since completing the University of Michigan Helen Zell Writers’ Program?

A: I was in the Helen Zell Writers’ Program from 2015-2018. There, I read my literary ancestors. I took creative risks. I had space to explore my voice. When I wasn’t in class, I was at coffee shops around town (Literati was my favorite). Those three years were invaluable to me. Since the MFA, I’ve been working as a senior writer at Hallmark Cards and teaching creative writing.

Q: How did your writing evolve over the course of your MFA?

A: My writing became more experimental as the program went on. Now I think of myself as an interdisciplinary artist who works in multiple genres. That desire to work at the intersection of forms grew as I read writers like Fred Moten, Claudia Rankine, and Harryette Mullen who reach for multiple modes of storytelling in their poetry.

Q: Concentrate is your first book. Tell us about winning the Cave Canem Poetry Prize for Concentrate.

A: I still remember the day I got the phone call. The news took a moment to settle it. It’s incredibly meaningful to have my book in the lineage of past winners I admire: Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon, Natasha Trethewey, and Tracy K. Smith to name a few. Concentrate is, first and foremost, a love letter to Black girlhood, and I think of Cave Canem as a place that fosters and nourishes Black women and their work. I’m proud that my first collection came into the world within that context.

Q: In the fall, you were on tour for Concentrate, and your book tour brought you to Ann Arbor. Did touring with your book change or solidify any of your thoughts about writing it?

A: On tour, I got to witness my book’s impact on readers, which definitely solidified the importance of the work. I thought of tour as my opportunity to give readers an inside look at my process, a perspective that they otherwise wouldn’t get. So my readings were set up as mini craft talks. I love the conversations that setup encouraged.

Q: Your new book includes images and different styles of poems. How does your work as a visual artist interact with your poetry?

A: Concentrate required me to handle, deconstruct, and make sense of the nonsensical force that is white supremacy. To write about a topic as complex and grueling as that, I had to call on many artistic forms. Taking a multigene approach was my way of examining the subject from different lenses. And I think it allows the reader to see the subject multidimensionally, too. I’m grateful for what poetry and visual art accomplish when paired together.

Q: The section titled “A thin obsidian life is heaving on a time limit you’ve set” contains a poem that borrows statements from a research paper from 2016. What prompted you to engage with the paper by writing a poem about it?

A: I knew I couldn’t write this book without research—not just doing it, but engaging with it on the page. Embedding research in Concentrate was my way of paying homage to the work done by scholars, writers, filmmakers, and leaders before me; it’s my way of saying, “This work is communal.” The particular research paper referenced in “A thin obsidian life is heaving on a time limit you’ve set” is about medical professionals’ false perception of pain tolerance in Black patients. There’s this racist assumption that Black people feel less pain than white people, which contributes to the life-threatening and life-altering mistreatment of Black people in healthcare. But, of course, we know that same dehumanization is felt well outside of medicine. It’s systemic. It’s perpetual. It’s in the murder of Latasha Harlins.

Q: About half of the way through Concentrate, a poem reads, “So I head to LA to handle the archive, to stand at the foot of every place I talk up, to earn the facts and their phantoms firsthand.” How did you go about researching your poems?

A: That quote comes from an essay I wrote after traveling to L.A. While in the city, I visited the places I most associate with Latasha Harlins’ memory: her middle school, her local rec center, Empire Liquor Market—where she was killed— and her gravesite in Paradise Memorial Park. Actually going to L.A. was a different sort of research. Finally, it felt everything I’d gleaned secondhand from scholarship was real, physical, undeniable. Going to L.A., putting my body in those places, was the most important research venture I undertook for this book.

Q: The timeline poems feel striking with the contrast of a darkened black-and-white image and black background with white text, such as the one that tells us, “Latasha Harlin’s gravesite in Paradise Memorial Park may have been disturbed….” The text is turned 90 degrees so the reader must rotate the book to read the poem. What inspired the visual appearance of these poems?

A: White space is something I implement throughout Concentrate. It creates breathing room and enforces a pause while reading, but in a collection that’s largely about the dangers of whiteness, I think white space is also commenting on white supremacy itself. I thought it would be interesting to have the whiteness broken up with a few black pages. That color contrast creates its own counternarrative.

The 90-degree layout decision was more technical: the timeline format wasn’t working with the page set vertically, so I made it horizontal. I’m glad the technical challenge made way for invention. Because of that, the book is one you have to turn and maneuver to read fully. I think that adds to its tangibility as an object but also adds to the idea that these topics I’m dealing with require a constant twisting and shifting of vantage.

Q: What is on your nightstand to read?

A: Such Color by Tracy K. Smith

Q: Concentrate was published in 2022, and now we are in 2023. What is coming up next for you?

A: Right now, I’m just letting the writing take me wherever it wants to go. I love being in that exploratory space again. I’ve been writing about family and doing more visual art lately. Maybe those two will come together to say something.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.