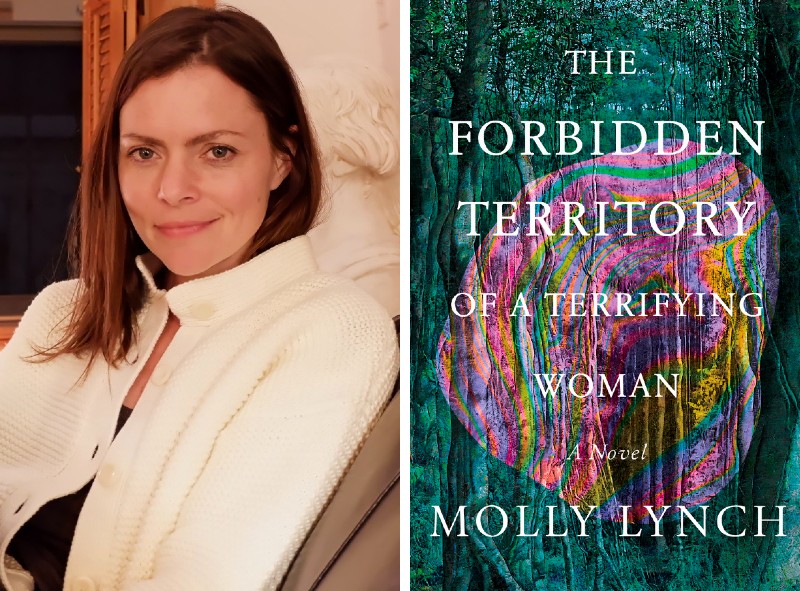

Late in the World: Molly Lynch's new novel tracks the willing disappearance of a mother and wife

Imagine that you have an urge to disappear and be unreachable.

Then, imagine that someone whom you care about has that urge, but you don’t know where they went or why.

Now, add many more layers of complexity to the woman who disappears given that she has a family, including a child, and a career.

These circumstances would raise many questions, and the premise of Molly Lynch’s new novel does just that.

The Forbidden Territory of a Terrifying Woman tracks Ada, a mother and wife who goes missing suddenly. Her husband, Danny, and son, Gilles, are left behind, bereft and confused. Yet, Ada is following her thoughts and feelings. With an omniscient third-person narrator, the reader gets insights into all the characters.

Early on in the book, the bond that Ada, Danny, and Gilles have with each other becomes clear, as “All three of them were one connected thing.” Yet, there are challenges:

Together—and yet there was Danny in the troubled silence of his thoughts, his stress, and Gilles, who was, on the one hand, their son, but he was also his own. And he was so much more his own than theirs. Or hers. That stunned you. How your child was fine without you. How he’d jump off rocks into a pool well over his head and swim with an instinct for keeping afloat. It made you almost laugh at his crying when he ran down a hill behind his school and fell. No, no! you wanted to say. You’re fine! Don’t you see? And it was true. But you still hugged him.

While they might all be independent, they need each other, too. The intimacy ties them together:

There was a closeness with them that sometimes shook Ada. One of them would sit up in the darkness to kiss the other one. Every part was known to the other’s lips and hands. It felt impossible, this loving. It would destroy you. Sometimes Ada lay awake in pain from it. Afraid of it.

This attachment makes it all the more surprising when Ada unexpectedly vanishes.

The novel goes on to search for answers about her disappearance, along with the disappearances of other women, which slowly becomes a phenomenon with the volume of vanishings. Ever present is Ada’s “fear of the future, or the reconfiguration of her relationship with the world since she’d become a mother, or the ways she felt intimidated by the role of mother, not to mention the act of raising a child so late in the world. It felt so late.” While these issues rise to the surface, they do not provide clear reasons. The characters must live their way toward understanding.

Lynch teaches creative writing and literature at the University of Michigan. I interviewed her about her new book.

Q: You grew up in Canada and Ireland and earned your MFA from the Johns Hopkins University Writing Seminars. How did you come to live and work in Ann Arbor?

A: I was offered a lectureship, teaching creative writing at the University of Michigan. The job brought me. I was delighted. There aren’t too many full-time jobs out there for writers.

Q: What was a formative writing experience for you, such as one in which you realized that you would write a book?

A: Through my twenties I lived in Montreal in a community of artists. There was a feeling there it was totally realistic and practical to commit yourself to your artistic practice, above everything else. Everyone was making work and sharing work. This was only really possible though because rent was still cheap and studios, gallery spaces, music venues as well as homes were affordable. Affordable space kind of allowed for people to “become” artists. It was during that time that I committed to my own writing practice in a way that felt irreversible. I think I knew then that I would write a novel.

Q: Your novel, The Forbidden Territory of a Terrifying Woman, is set partly in Ann Arbor. How does place influence your writing?

A: Place is vital to me in writing fiction. My characters are entirely informed by their connections to the places they’re in. I can’t separate my characters from their geographies, nor their particular historical moment, nor any of the cultural details—the texture of life around them. Place is more than backdrop, it’s a medium, it causes my characters to feel the things they feel, it shapes how they know themselves, what they want, what they fear. This novel was set in a place that I was also living in, and I found that incredibly inspiring. I could step outside any day and gather material and imagine my characters’ feelings in relation to that place. Yet I don’t think you need to physically be in a place in order to write about it.

Q: The Forbidden Territory of a Terrifying Woman contains an ongoing mystery that unfolds over the whole course of the book. Did you know where Ada goes from the start of the novel? How did that change how you wrote?

A: In starting the novel I had two contending ideas about what happens to Ada and where she goes. One is mythological, based on concepts of metamorphosis. The other is more concrete, at least in that it relates to a diagnosis of a psychological condition of dissociation. I kept both possibilities alive in my mind as I wrote because I wanted to play them out, particularly in Ada’s character. As she tries to figure out where she went, I wanted her to explore what it would mean to have literally changed form. I wanted the reader to explore that too. Though in the end, I made my decision about where she went, I didn’t want to hand that answer to the reader in a tidy package as might happen in a more familiar genre novel. I wanted them to ask the questions themselves, to explore both the mythological and the psychological/sociological possibilities and what those would mean. What would it mean to “merge” with the natural environment? Similarly, what might it mean to lose track of your identity and wander away from your home and life?

Q: How did you develop this writing style with no quotation marks for dialogue and an omniscient, third-person narrator? How does this style serve this novel?

A: It actually happened very spontaneously in my first draft. It came out of the narrative voice, which felt to me like a voice similar to the characters’ speaking voices. Quotation marks might have felt like an interruption to the intimate aspect of the two narratives.

There are also a number of writers whose work I love so much, who have let go of quotation marks, or who play with punctuation in ways that feel true to their voices. Many of those stories are very much about how they’re told. As a reader and writer, I am probably as interested in voice as I am in story. I love reading stories in which it feels as if the narrator is speaking as they would in real life. I love the honest feeling of that kind of writing.

Q: Danny experiences some heart-wrenching weeks with Ada gone. It is hard for him to even function, as “He heard his voice from the outside, desperate, not understanding anything: how to walk, how to think, how to breathe.” The narrator’s insights into each character are stark. They are each in very different positions. How did you develop these contrasting perspectives of Danny, Gilles, and Ada?

A: I feel like this is the challenging and important work of creating fiction. I think that developing characters takes some “embodying” of those characters—to use some academic language! When I teach fiction, I encourage my students to go on walks with their characters or to do some kind of meditating—whatever that means to the student—to get into that character’s feelings. But in a way, for me, it all comes back to finding the character’s voice. I definitely did some waiting, listening, and feeling in order to finally hear Danny’s voice. Ada’s voice was easier. It was the first voice to come and I guess her character resembled a person like me a little. More. Once Danny’s voice came to me it almost wrote itself.

Q: I loved the line, “It felt so late,” which refers to the world and motherhood. How do you see this novel relating to the current moment in time?

A: I guess I feel that the novel is really about the current moment, a moment in which it can be very difficult to imagine what the planet will look like in the very near future—importantly, what that means for your children. It’s weird to raise children in a time in which things feel so unforeseeable. It’s possible that I have this supposedly “negative” perspective because I come from the West Coast, where every summer has been choked in smoke with ash falling from the sky, for the last decade. The alarm bells have been blaring there for quite some time.

At the heart of the novel is a dilemma—in fact a crisis—about how to carry on a comfortable, domestic life, while the earth and other bodies are being destroyed. I feel that that is a dilemma for all of us. A dilemma of our time.

Q: What is on your nightstand to read?

A: I have an absurdly huge stack of books on my nightstand. I have a lot of nonfiction and poetry, some histories and theory relating to the novel I’m writing now. As for fiction, I’ve been slowly reading Bernardine Evaristo’s incredible Girl, Woman, Other. I’m also burning through a book of stories called Send Nudes by a brilliant young British writer, Saba Sams.

Q: What are you writing next?

A: I’m deep into another novel, but I’ll have to wait before I can say anything about it.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.