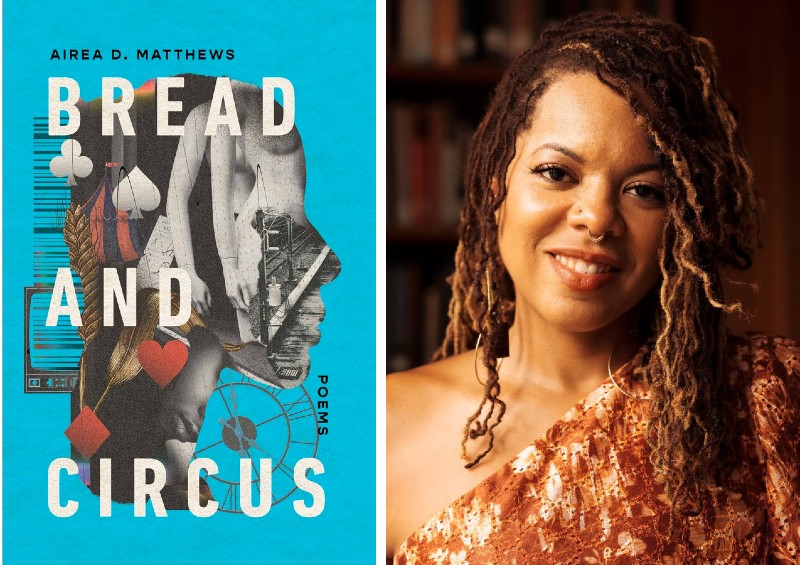

Public and Personal Policies: Airea D. Matthews’ autobiographical poetry collection questions economic theory amid the realities of poverty and violence

Necessity and amusement. Sustenance and transaction. Security and turmoil.

Airea D. Matthews’ autobiographical poetry collection, Bread and Circus, brims with contrasts. One situation or item is paired with another to show a lack or miscalculation. The poems hover on a precipice, even as the guests “…watch a lovely commodity / reluctantly agree to her own barter.”

Early in the book, the poems witness a shotgun marriage, and the family grows in the subsequent years. Making ends meet results in how “Papa despised the vestiges of a hand- / out” – and especially “one specific symbol of his failure – corn.” Over time, the father’s drug addiction causes trauma, along with broken promises like, “I owe you a bike, right?” though it never materializes. These memories stick in the poet’s mind, as the poet reflects on a past hurt:

My ex-

communicated ex-Navy father:

Come here, Boy (though I was a girl

he called me boy because

he wanted one).

……he grabbed

the back of my neck, pulled me

close to teach his only lesson

worth remembering: Cry, Boy,

look that honest wound in the eye

and you betta let this mutilated

world see what she did to you.

The lesson is an important one despite their tumultuous relationship.

As the poet moves forward—“Either this is a free country or / the dream is wildly overpriced"—not only does more loss and pain await but also healing and a new generation. The poem “The Rules of Attention” reflects on “some other mother’s loss” as being the “Wrong place, wrong minute, wrong / color, wrong body.” This fraught distinction becomes painfully subtle because, “What matters is knowing the distance between / a wink and a blink, what harms and what suggests harm, a variance measured in milliseconds.” The poet makes the significant, life-affirming shift from focusing on the help or bike that never came to caring for her children. A poem later in the book, called “Nevertheless,” offers “Praise to all who rejoice in becoming / Amen to all who transform in return.” The poet’s resilience carries the book to a new outlook.

The poems in Bread and Circus take different forms, from prose to sonnet. Each new section is marked by a title, graph, and quote from either Adam Smith or Guy Debord. Themes from both philosophers are threaded through the book. Some poems employ found poetry in Smith’s text. For example, “Smith on Exchange” brings the lines, “Give me / that which I want, / and you shall have / this which you want.” The poem “On Real Costs” adds that “every thing / is bought with / our body” and also that “toil / is / the first price[.]” However, the poet discovers that these theoretical exchanges do not bear true in the chaos that is poverty and violence.

Matthews holds an MFA from the Helen Zell Writers’ Program and an MPA from the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, both at the University of Michigan. In 2022, she was named Philadelphia’s Poet Laureate. She is an associate professor and co-directs the poetry program at Bryn Mawr College.

Matthews will read at the Center for Racial Justice’s event at the University of Michigan’s Ford School of Public Policy in the Annenberg Auditorium in Weill Hall on Thursday, November 9, at 6 pm.

Q: What inspired you to go for two degrees at the University of Michigan?

A: I worked almost a decade in the private sector after graduating from college and moved to Detroit in 2000 with one young son and another on the way. I’d dreamed of being a writer in every iteration of my life, but I didn’t understand a clear path toward that goal. Not to mention, my working-class roots didn’t seem to make space for sustainable possibilities in the arts. And then, shortly after I left the private sector, I was accepted into the Ford School. My writing tutor in the program helped me to see possibilities for my writing outside of the private or nonprofit sector. I began to see the arts as an avenue for change. When I left the Ford School, I found my way inside the performance poetry community in Detroit. That community was upholding the griot tradition, and I felt like I could frame the happenings in the world through a humanistic and artistic lens—instead of briefs I wrote and performed poems. For several years I was a freelance teaching artist [who] supplemented poetry and performance curriculum in public schools until I was accepted in the MFA program in 2011.

Q: You now are a professor and co-director of the poetry program at Bryn Mawr College. You have also been the poet laureate of Philadelphia for 2022-23. What does this work involve?

A: Much of my work as a poet laureate is geared toward promoting the arts in the lives of the residents of Philadelphia. What I realize through your question is that I am serving in a role which would have helped me see the potential of the arts when I was younger. My work as a professor and co-chair is not different. I feel that I am lobbying for and teaching poetry to those who have yet to fully experience a life devoted to language and texts that converse across centuries.

Q: Your expertise in public policy and economics permeates your newest book, Bread and Circus. When did you see that your art could intersect with your previous focus?

A: When I was an economics undergrad, I would write short haiku-like synopses of the graphs and concepts that I was learning. The form helped me to recontextualize the spatial dimensions of the graph. Even then, I was considering how text and space converge to form meaning, and that’s essentially how my art intersects with my other interests. Whenever we write we ideally bring our full selves to the page—I am who I am largely owning to my interests and those things that I choose to focus on.

Q: In fact, some of the poems in Bread and Circus are found poems within the text from Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. The poem is in the words that are bolded. How did you land on this form, and what do you like about it? How did you play with form throughout the book?

A: Structurally, when I originally conceived of the idea of a poetry collection that intersperses economic concepts, I envisioned the extracted texts—what some call erasures—to be actual graphs that I’d honed into poems. However, as I concentrated on certain textual sections from The Wealth of Nations, I wanted to challenge myself to sit with the original text and have some way for the reader to grapple with dual meaning, as I did. To enact that, I decided on palimpsestic poems that require attention to the extracted sections as well as the original text, differing significantly from the true erasure in which the original text is illegible. Another fun fact about the extracted poems is that they are interactive. When held under light—an actual light—the authorial interpretation becomes increasingly clearer, while the legibility of the original text makes it possible for readers to hew their own interpretation.

Q: As a memoir-in-verse, Bread and Circus is autobiographical. Did you set out to write a memoir-in-verse, or did you notice that your poems were coalescing as such?

A: I had no intention of writing a memoir-in-verse, but the poems apparently wanted that structure. The hardest part in writing this book was reconciling what the book wanted to be with what I wanted it to be—personally and structurally. After I wrote my first book [Simulacra, 2017], I hoped to write about poverty, race, and class. However, the poems I was writing at that time—none of which made it into the book—felt removed from those concerns. I let time pass to find another way inside my desires. I started reading more autoethnographic work in which the lived experience can be linked to research or cultural phenomena. That simple expansion gave me permission to use my life as evidence and to allow myself to be fully present as a participant in the system.

Q: Poets preserve some distance from their poems in that the speaker is not always the poet. How does the memoir-in-verse change this connection to the poetry?

A: Well, with the memoir-in-verse, one can safely presume the speaker is the poet. The framework allows movement closer to the personal “I.” With my first book, which was an anti-confessional, I offered a capaciousness between the speaker and the poet. With this book, I was more inclined to walk fully inside the confessional tradition.

Q: The book advances chronologically, starting in the late '60s and going forward to recent history. In “Haunting Axioms,” the last two lines say, “Some ghosts return to their wound. / This is always true of the living.” The poems do this, too. How might poetry help us cope?

A: Poetry allows us to return to ourselves with some distance and objectivity after time passes. And since poetry comes directly through the subconscious, poets can’t help but be affected by what we find in the recesses of our psyche and try to make that legible through our words. It’s a good practice to dredge our own fluid depths and find the gold buried there while learning to live with our own shadows.

Q: This book is “a bold poetic reckoning with the realities of systematic poverty and its intergenerational effects.” The first poem, “Legacy Costs,” reads, “their heirs wasting / a w a y / among brothers / fattened from lamb.” These lines illustrate inequalities that should not be there. How do you see your book bringing together the personal with flawed economics and social issues?

A: The term "economics" is derived from the Greek word oikonomia, meaning household management. My thought in making the book was that to understand the rules of one’s home, or household management, can also govern one’s outlook outside the home. Inside my home, there was a sense that the person was commodity—partially owing to my parents’ own upbringing. The commodity is not autonomous. The commodity serves at the pleasure of others. For a person to be viewed as commodity says much about one’s worldview and importantly how entrenched society is in production and exchange of commodities, even if the commodity is the body. For me, I couldn’t be in conversation with Adam Smith and Guy Debord without considering the ongoing afterlife of the transatlantic slave trade—an epigenetic trauma—and how, still, embodied blackness in the U.S.—whether home or out in the world—is often viewed as fungible. As for the visual elements, the echoes of economic graphs in the book are attempting to visually convey how very unstable our relationship is between theory and reality while whispering the ways in which disequilibrium persists.

Q: What are you reading and recommending?

A: It is such a rich publishing year! I just read sam sax’s Pig, David Waldstreicher’s The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley, and Safiya Sinclair’s How to Say Babylon—[all] marvelous. I am currently reading Jesmyn Ward’s Let Us Descend. My ancestral research for my next book has led me to reread historical slave narratives and accounts including: The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, Written by Himself; The History of Mary Prince; Celia, A Slave Trial; and a volume of collected works titled Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies edited by John W. Blassingame. I usually read something different at night than during the day. Recently I have been reading chapters of Paul Stephens’ The Poetics of Information Overload.

Q: What is next for you?

A: A wise mentor once told me that once you finish one book, you mentally move to the next one. My next project is in its early stages, but it will be about forms of resistance and migration. I am also in development of a screenplay and opening an arts commune in Troina, Sicily. Writing, thinking, plotting, planning, and more writing, as they say.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.

Airea D. Matthews reads at the Center for Racial Justice’s event at the University of Michigan’s Ford School of Public Policy in the Annenberg Auditorium in Weill Hall on Thursday, November 9, at 6 p.m.