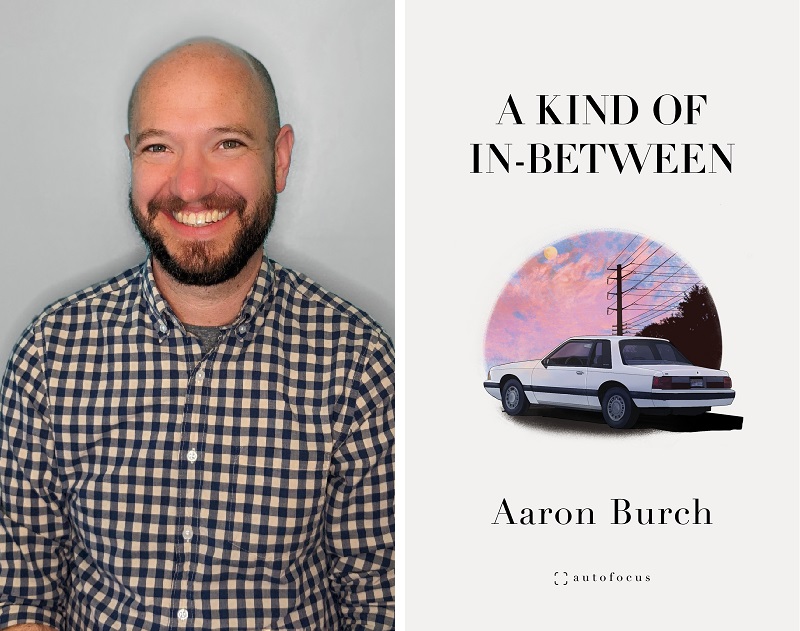

AARON BURCH EMBRACES AMBIGUITY AND NOSTALGIA IN HIS NEW ESSAY COLLECTION, “A KIND OF IN-BETWEEN”

Aaron Burch recounts major life changes and memories in the essays of A Kind of In-Between. Throughout the pages, Burch questions what is important in life. What do you remember? What does it mean? Why are you happy or not?

Focusing on the places he has been is one approach that Burch takes to inform these inquiries. He shares that he grew up in Washington and has subsequently lived in Michigan and Illinois as an adult. In the sentence that lends itself to the book’s title, he narrates his road trip:

I’m somewhere in the middle of Pennsylvania, driving around this big, long turn while also going down a decent decline. I don’t know how steep; I don’t really have any idea how to measure or guesstimate that kind of thing. I can tell it’s steeper than anything in Michigan but less so than Washington, a version of the kind of in-between that I return to again and again—known but not, neither childhood nor adult, not quite then or now, here or there.

This ambiguity begins in the physical world and then seeps into other contexts. The human urge to name and define things breaks down when something is neither one nor the other. Burch concludes this essay called “Ohiopyle” with a question: “Were you to ask me, somewhere in the middle of Pennsylvania, whether home meant Washington or Michigan, what would I answer? I’m not sure.” Still, maybe one does not have to decide, as Burch highlights “the interconnectedness of everything and everyone” in the first essay of the collection.

The way that Burch considers not only place but also the past, relationships, and circumstances is admittedly nostalgic. In “Word Math Problems (2019),” he writes:

I’ve been doing this thing more and more as I get older, more nostalgic. I do the math, backwards, forwards, figuring out how old I was when, how old I am now. Memories and events and people as benchmarks, as frames of reference. Venn diagrams of figurative and literal size, age, meaning. The speed, the size, the shape of a parent, a dad, a child, husband, teacher, adult, human.

Time and changing roles can be surprising. For Burch, even email drafts are a moment in time to be remembered. Burch desires his to be organized as “a folder of things that at some point I felt needed to be sent but then knew also to be better left unsaid.” The reality, however, is not always as clean, and some drafts instead form “this graveyard of unimportant ephemera.” There are aspirations, and then there is reality.

Then again, and perhaps thankfully, other things do not hang around indefinitely and uselessly. Another essay, titled “No Longer There,” wonders about a tree that is felled and puts it in the category of “these things that disappear when we’re not looking, these things that were there in some moments of our lives and then, in other, later moments, no longer are….” How is it that some things remain in one’s life, while others go? Burch suggests that we may never know.

Burch teaches at the University of Michigan and lives in Ann Arbor. Pulp interviewed him earlier this year about his novel, Year of the Buffalo. I caught up with him again on his personal essays in A Kind of In-Between, as well as his work as an editor.

Q: How is life in Ann Arbor since we last talked earlier this year?

A: It’s good! Because I’m a teacher, I’ve come to really think of time and the year through that academic lens of the semester, and so that’s really how I often think about Ann Arbor too—where I am in the semester, the joys of summer, etc. I’m right now in the final week or two of my semester. You’d originally reached out at the beginning of the semester and that … says a little something about the chaos and busyness of this semester in particular, which has me all the readier for a little break and the holidays.

Q: I hear you on looking forward to a break. Your books were published close together! How did that come to fruition? Were you writing them at the same time?

A: So goes the weird chaotic timing of writing and publishing! I wrote the novel, Year of the Buffalo, over so many years and it took so long to come to fruition. This essay collection came together totally differently, and as something of a bit of a surprise, with many of these (primarily) short essays after I was “done” with Year of the Buffalo but before working on final edits and then having it published. [Having] them coming out so close to one another is exciting but also probably makes it look like there was a lot more overlap than there was, and that I’m much more productive than I actually am. They’re really the culmination of years and years [of work] that happened to be released so close to each other.

Q: Our previous interview was about that novel, Year of the Buffalo. Now we are talking about your essay collection. How does your writing process change (or not) between fiction and nonfiction?

A: The day-to-day process is pretty simila: sit at the desk, try to get some words down and make a little forward progress. That said, the novel is so much more invention—What should the characters do now? Where should they go next? What if this happened next?! The essays, by contrast, are a little more rooted in reflection, and [it's about] picking and choosing what is a moment or memory or idea or whatever is worth grabbing hold of and writing about.

Q: Some of the essay titles merge into the essay itself. They are practically the first line of the essay, as in the piece called “I Never Made Anyone a Mixtape” in which the first sentence begins, “I never received one either….” What draws you to this approach? What does this approach allow you to do in the essay?

A: I think I am constantly trying to be influenced. I’m trying to, in various ways, cultivate in myself being inspired and borrowing and kind of filtering everything, at least to some degree, through this lens of creation and invention. That means, sometimes, looking at a painting and thinking, “What might the writing version of that kind of brush stroke be?”

Or listening to hip-hop and wondering what my version of a verse versus a chorus might be, or a guest feature, or whatever. That title as the first line of the piece is a pretty common poetry “move” that doesn’t not exist in prose but certainly seems less used, and so—and I don’t even remember at this point if this was conscious or not—I borrowed that idea and tried to play with it. I think poets often think about titles more than prose writers, and I like that cross-genre borrowing. But then, a lot of these essays are short shorts, almost like creative nonfiction, or CNF, prose poems. It became an opportunity to think about how much you could say in as few words as possible and that means using everything you can, including [the title].

Q: These essays are personal. They start with the pandemic and zigzag between the present, such as the email drafts in your inbox, and your childhood, which included being adopted. How did you decide what to include or what felt too vulnerable?

A: This is a boringly vague answer, but I think often it’s just intuition. What feels right? I’m not always the most open, vulnerable person, and I think there’s surely lots I could have written about but didn’t. I don’t think I ever consciously avoided anything because it felt too vulnerable. More often it comes down to: “Can I find something interesting to say about this? Can I look at this idea or memory or object (or whatever) and try to look at it and/or present it in a new, interesting, unique way (that hopefully also feels as honest and true as possible)?”

Q: In addition to writing your own books, you are a founding editor of Words & Sports. How did you decide to start a journal?

A: I came to write (and read more extensively) in the smaller and indie press worlds through lit journals and more or less at the same time as I was starting one myself. Way back in 2001, I started Hobart after my undergrad. At the time, I started it really kinda as a lark, to entertain myself and my friends, and just as something to do for fun at a point in my life when I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. I ended up falling in love with working on the journal, the community it gave me, and the excitement of getting to work with writers and publishing and trying to find readers for writing I believed in. In the last few years, I started a couple of new journals with co-editor Crow Jonah Norlander, [including] Words & Sports and HAD. Both were “pandemic babies” [and] started during the time of lockdowns. I was probably looking for ways to keep myself entertained and to have fun, which I guess is a kind of 20-years-later echo of why I’d started Hobart and gotten into this whole world in the first place. Both started with an idea that seemed fun and interesting: a journal built entirely on short, spontaneous, “pop-up”-style submission windows (HAD) and a journal focused on writing about sports, but not “sports writing.” We really try to have as much fun with all the various interpretations of what that might mean (with Words & Sports).

Q: What does your work as founding editor, as well as editor of some of the Words & Sports issues, involve?

A: With W&S specifically, it is more of a “managing editor” role. Crow and I select editors for every quarterly issue and then mostly try to be as helpful as possible in giving them the resources to put together an issue they’re excited about and proud of.

Q: You also post on social media about the submission and writing processes. What have you learned from being an editor? How have you applied what you have learned to your own writing?

A: I do kinda love tweeting about it all. Mostly, I just think it’s fun. And I think I like trying to demystify the process somewhat. I think, as an editor, I’ve learned how subjective it all is. I don’t take rejections that personally or seriously because I’m so often on the other side. I know how much it can just come down to personal taste and also that mysterious distinction between a story being “good” and an editor/reader FALLING IN LOVE WITH IT. But then, too, I think reading so many submissions over so many years has helped me both refine my taste and understanding. It’s given me a better idea of what I think makes a story work versus not, what makes a story stand out, what can make a story fall flat, etc.

Q: Speaking of reading, I asked about this last time, but I’m curious what’s new. What is on your stack to read?

A: I just finished Ling Ma’s collection of stories, Bliss Montage. I didn’t love all the stories, but the ones that I did immediately became all-timers for me. And, before that, I finished Lindsay Hunter’s new novel, Hot Springs Drive, one of my favorite two or three books I’ve read this year. I’m a little between books right now. Mostly focused on trying to finish this semester, but then I have something of a break and am excited to pick up a few books I haven’t had time for. Adam Levin’s Mount Chicago and Josh Denslow’s Super Normal are on the top of that pile right now, but we’ll see what grabs my attention once I post final grades.

Q: What is next with your writing?

A: I’m working on a novel that I was hoping to be a little closer to done by now, but so it goes. It’s set at a youth group lock-in in the ‘90s, so it's incorporating a lot of the themes I’m always writing about (childhood, growing up, nostalgia, religion, sense of self) with these interesting and really fun constraints of it being a single location [for] one night. A little like a locked room mystery, but without a murder (probably?).

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.