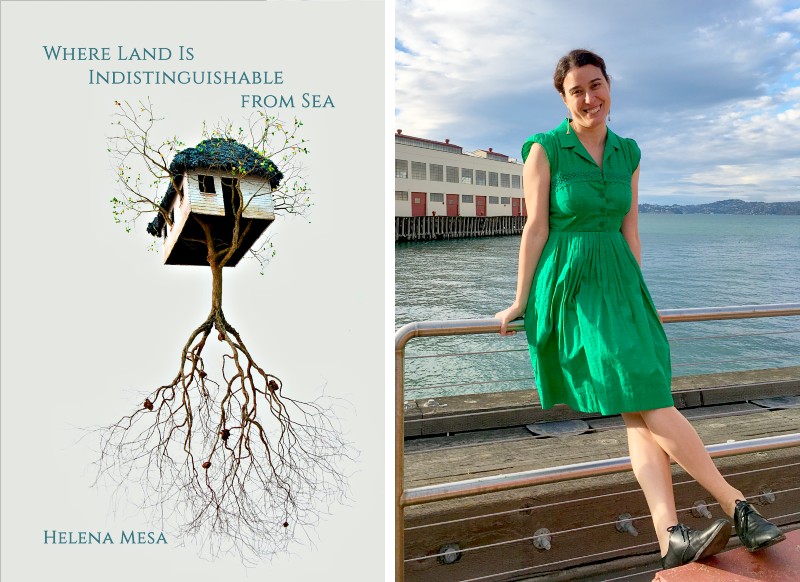

Helena Mesa discovers “Where Land Is Indistinguishable From Sea” in her new poetry collection

Helena Mesa measures the space between places and people through the poems in her new collection, Where Land Is Indistinguishable From Sea. The poems teem with longing, whether from loss or distance or both.

This longing is sometimes for a person and other times for a place. In the poem “First Year Gone,” the poet speaks to an unreachable person as she undoes her knitting:

You’ve become

a dream, my lips tasting only

damp wool, an ocean bed

drained of seawater, its kelp

drying in summer heat—if only I could

cross the dry basin

before storms flood the ocean once more.

The impossible task of traversing the ocean bed illustrates how “you remain as far now as you were / when I first knit these rows.” The loss is a drought, and more storms are on their way.

Another poem, “After Exile,” narrates some attempts to feed another person’s bird after she has left. The bird does not eat: “It understood longing hungers longer / than anyone could hold out / their hand.” Mesa, too, understands what it is like to not have the one thing that a creature needs, the one joy in this all too bleak life.

Religious undertones permeate the poems, especially Eden which appears in several places even though “I did not ask to be an Eden.” “The Lesson” reflects on the concept of God’s presence when “She said, He is everywhere, / even inside you.” While Eve must deal with her shame in the garden after eating the forbidden fruit, the shame becomes a side effect in Mesa’s poem. Exile moves to the forefront, and it is even a foregone conclusion at the outset of sin because “He lived inside her / and felt the thought form.” Another poem calls forth “Lot’s Daughter,” and the poem titled “The want for faith” describes the tenuous nature of faith that allows one “to glimpse / what might be the blurred edge / of a dog chasing a hare / or nothing at all.” Clarity is elusive.

The longing in these poems brings not just the ache of loss but also the occasional fruit of “sweet persistence.” The poem named “Waiting to Meet in San Francisco” is breathless with hope, and the poet takes the imperative to implore: “Say yes. Say you will / let go, say you’ll never, / say air will catch us both.” The time of day also brings splendor, as “Morning crackles more clearly through the trees.” Brightness seems to cut through the grief and desire.

Since some loved ones are gone forever and religion does not provide all the answers, Mesa’s poems continue questioning what distance means. Mesa’s parents left Cuba for the United States when they were young, and that drastic move informs poems in the collection. The recurring questions about time and space appear in multiple poems, such as “Catalog of Unasked Questions,” which starts with the lines:

How far before home

receded beyond the horizon?

(54 km) How far before It’s too late

to turn back? (22 km)

The mileage and time add up. These totals may or may not change the outlook, as the last question of the poem asks:

…And how far

Before the distance

No longer felt distant?

( )

Distance is the reality as “Everyone I’ve ever known / lives so far.” Fulfillment remains out of reach given that “The map to reach you pale and wordless” does not offer answers to close the distance.

Mesa lives in Ann Arbor and teaches at Albion College. I interviewed her about Where Land Is Indistinguishable From Sea.

Q: What brought you to Ann Arbor?

A: In 2003, I moved to Michigan to teach at Albion College after completing my doctoral degree at the University of Houston. I lived in Albion for four years but settled in Ann Arbor to be in a larger town and connect with the local arts community.

Q: What do you teach at Albion College?

A: I mostly teach creative writing classes, specifically poetry workshops. Last semester, I also taught Latinx literature and loved exploring a range of contemporary works from across the diaspora.

Q: The title of your new poetry collection, Where Land Is Indistinguishable From Sea, is evocative. The title also appears in the last lines of the poem “Paradise Island.” Tell us how you decided on this title.

A: The inspiration actually arose from Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman. When I wrote “Paradise Island,” I was rewatching the film and found myself transfixed by the scene where Diana says goodbye to her mother. Hippolyta says, “If you choose to leave, you may never return.” I imagined my own mother leaving Cuba for the first time in 1961, sensing the fear that she must have felt, both in leaving and the possibility of never returning. And, certainly, when she did return 50 years later, she didn’t recognize the place she once knew.

That scene ends with a shot that lingers on Diana as she watches the landscape shrink in the distance. When I wrote the lines “where land /is indistinguishable from sea” in response to the film, something clicked. For a long time, I’d been thinking about geographic and emotional spaces that connect us, separate us, and how we might love across great distances. Strangely, that Wonder Woman scene offered the visual metaphor I’d been seeking. Diana can no longer see her mother, but she also can’t see the blurry shore—the place that holds her past.

Q: The poems are prefaced by quotes from Louise Glück and Eavan Boland. How do these writers converse with your collection?

A: The epigraphs nod to my love for both Boland and Glück. I often turned to their books while writing the poems that inhabit and subvert myths. Boland’s In a Time of Violence especially taught me what poetry could be and do when I first encountered it in the late '90s.

Both quotes resonate for me in different ways. I hope that Glück’s “The night isn’t dark; the world is dark” establishes the tone of the book’s first section, and that the plea of “Stay with me a little longer” reads as an invitation to the reader. The second epigraph comes from Boland’s “Love.” The line, “But the words are shadows and you cannot hear me,” speaks to the struggle to communicate between different figures within the collection, such as the mother and her daughter, the exile, and Cuba.

Q: Next, a poem called “Love Letter to a Stranger, with Rain” begins the book prior to Part I. The poem asks, “Why wait for the sirens? / Why not sing like that now?” Could this poem be a sort of Ars Poetica?

A: I hadn’t thought about the poem as an Ars Poetica, but it certainly could be! Especially in the desire to speak, speak now, and to begin again in order to “get it right.”

I wanted to suggest that sometimes the person we know best could be an emotional stranger and that the person we dream of might always be an idealized stranger. My hope is that by beginning the book with this poem, it will serve as a love letter to both. In that way, I believe the poem might show the reader how to read the collection that follows.

Q: How does the collection change over its four sections?

A: So much of the book contemplates love and longing across vast distances. For example, many of the poems consider my mother’s emigration to the United States after the Cuban Revolution, both her isolation living in an unfamiliar country and her estrangement in returning to her homeland. I should say that although the Cuba poems are a prominent thread, the book isn’t only about my mother. That is, while the poems are inspired by my mother’s experience, and my own experiences, the two figures become archetypal figures.

The first section begins with estrangement (“Late”) and dwells on the desire for love and closeness in an imperfect world. More plainly, the world’s a little cold. The speaker is also longing for romantic and platonic intimacy but struggles to open herself to the possibility of love.

Section two “looks back” in the sense that it introduces the mother and her departure from Cuba. The speaker looks to the past as a way to understand her mother, to understand how exile affected her, and to understand love.

The third section signals a return “home” to Havana. In some ways, despite their different experiences, the mother and speaker are parallel to one another—they are both longing for something that feels unattainable: a country, a homeland, a beloved, a connection, a closeness. They are both facing their own griefs and struggles—the mother cannot find her father’s grave because it’s been exhumed (“Prayer for the Exhumation”), the daughter is struggling with her own loneliness (“Navigation”).

And, finally, in section four, the daughter more clearly sees her misperceptions about her mother and Cuba. The speaker also chooses love despite her doubts—the book ends on the speaker seeking and believing in love, the two lovers living together in the same home.

Q: Some of the lines mourn through memories, as we can “See Hessian hills, / the color of your grief.” How do you see grief showing up in this collection?

A: Oh, yes, grief runs through so many of these poems—my desire for love and struggle to accept love, the struggle to connect with those around me, my mother’s grief in leaving behind her homeland—a place where she could not return— my mother’s uncertainty in entering her childhood house after 50 years, my own struggle to understand my mother’s experience. Perhaps that’s why my impulse was to end the collection on a coming together despite the world’s flaws—the two lovers finally living in the same place, the speaker imagining spring lilies “tangled in their wild joy,” the invitation for closeness in “Prayer for No Country.”

Q: “Duende with Poppies” contemplates the color orange. A stanza reads:

Rothko orange, neon orange, orange I’d wear

in deep summer,

orange the sunlight would be

if given a choice. A chorus of baritones,

a few tambourines.

How does the duende form influence this poem?

A: In June of 2020, I was reading Lorca’s “Duende: Theory and Divertissement,” Hirsch’s The Demon and the Angel: Searching for the Source of Artistic Inspiration, and a lot about COVID. I was fascinated by Lorca’s perception of duende, particularly its ecstatic quality. He says, “One returns from inspiration as one returns from a foreign land. The poem is the narration of the voyage.” That estrangement interests me—seeing the world as if I were a foreigner, as if estrangement might push us toward connection or pull us into isolation.

The neighbor across the street is a terrific gardener, and that June, his flowers were in bloom, including some stunning Iceland poppies. For whatever reason, their orange spoke to me—perhaps because the orange was bold and beautiful and the color of warning signs, or perhaps it was the delicate nature of a bloom that only lasted a few days, or because it was early in the pandemic and crossing the street to hover over a neighbor’s flowers felt transgressive, or perhaps it was my personal associations. But I felt that ecstatic quality, that inspiration, and saw the poppy in an extrasensory way, one that seemed hyperaware of both beauty and death.

Q: The concepts of “there” and “here” appear in multiple poems. The poem titled “There” identifies the contexts in which the word appears, such as “No, there, the logistics of marking a place….” What did you learn about these words—here and there—through writing these poems?

A: For years, my sisters and I said we wouldn’t visit Cuba without both my parents. Although my father had returned multiple times throughout the decades, my mother bitterly refused—it was too emotional. She finally agreed, and in 2011, we left behind husbands, partners, and children, and traveled to Havana for the first time. Over and over, my mother thought she recognized streets and landmarks and neighborhoods, only to realize that she was somewhere else. “There” captures the experience, and it defuses the word “there” through its different uses and meanings of the word.

I grew up with that idea of “there,” of “over there”—as in, Cuba—versus here, in the United States; that distance always felt like an uncrossable divide, until it wasn’t. When I fell in love with a woman who lived halfway across the country, the distance between us seemed unfathomable, but eventually, we closed the distance. We walked down the street, held hands.

Although geographic distance is literal in the book, it’s also metaphoric. And, for me, geographic distance feels less difficult than the emotional distance between family or loved ones—a distance that we’ve all felt at some point within our lives, even if, like Diana leaving Paradise Island, it is simply the first time one leaves home. Neither the romanticized paradise of over there—or of the past—or the imagined paradise of over here—or one’s present—is complete. Neither encapsulates who we are without the other.

Q: What are you reading and recommending this fall?

A: I’ve been reading a lot of prose. I just finished Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age and strongly recommend it! Also, Javier Zamora’s memoir, Solito, and Manuel Muñoz’s latest short story collection, The Consequences—both are terrific!

Q: You have written two poetry collections. What is next for your writing?

A: Call me superstitious, but I’m afraid to describe the new book project because it’s still a bit ethereal. It’s in reach, and my notes and rough drafts are guiding me; I just need to think and write some more before I can define it to someone else. Ask me a little later?

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.