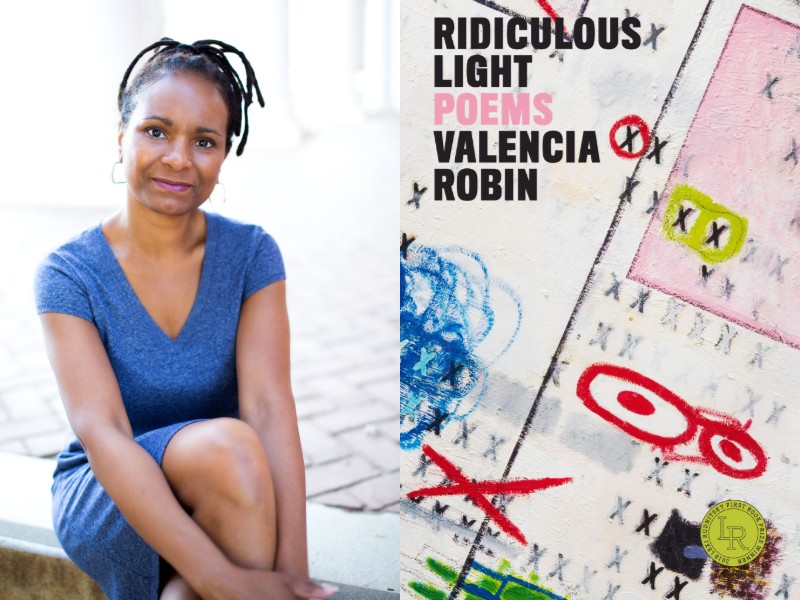

Valencia Robin’s poetry collection "Ridiculous Light" spans time, space, and seasons -- from Milwaukee in the 1960s to Ann Arbor in the 1990s

This story originally ran August 12, 2019.

Valencia Robin’s new poetry collection, Ridiculous Light, spans time, space, and seasons -- from Milwaukee in the 1960s to Ann Arbor -- and offers moments of distinct observations. The speaker invites readers into specific recollections and, within them, shares not just what happened but vivid descriptions and sublime reflections on the natural world, people, identity, and experiences.

A poet and painter, Robin is one of the founding members of GalleryDAAS at the University of Michigan. She now lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.

She will return to Ann Arbor to read at Literati Bookstore on Friday, August 16, at 7 pm, and Pulp interviewed her before her visit.

Q: You lived and worked in Ann Arbor, including earning your MFA in Art & Design from the University of Michigan. What do you remember about your time here?

A: I spent most of my adult life in Ann Arbor. I moved there in the early '90s. Besides the wonderful community of friends that I have there, what I love about Ann Arbor is that it’s a great walking city. I love to walk. So when I think about my time there, I often think of walking with one of my girls along the Huron River or in the Arboretum.

Q: Poems in your new collection, Ridiculous Light, mention places such as Kerrytown and Milwaukee. What is your connection to Milwaukee? How has your time in these places shaped your view of the Midwest?

A: I don’t know that I have a view of the Midwest, especially through the lens of two such different cities. I grew up on the north side of Milwaukee, which was mostly black and working-class, but I left the city when I was 17, and if you’d asked me back then, I would’ve said that nothing important had ever happened to me there. My family was part of the Great Migration. Home to them was Atlanta by way of West Point, Georgia. I was actually surprised to realize that I had two poems with Milwaukee in the title because I was one of those kids who couldn’t wait to leave home. It really wasn’t until I began writing “To Milwaukee,” a poem in the form of a letter to the city, that I realized that Milwaukee and I had a story to tell, that all those seminal moments of childhood could add up to something worthy of a poem.

Q: Trees figure prominently into your poems, such as in “Aubade With Sugar Maple” which offers the lines, “And yet somehow that maple knew me. We talked / and talked until I became birched and oaked, / crabappled and cherried—drunk / with all the tree-ness I’d forgotten. / My God, to think—I could bud, even blossom.” What draws you to trees? How do they inspire you?

A: Trees have always been a source of joy for me; when I look out my window or walk past the same tree year after year, it starts to feel like an old friend. I don’t think I’m alone in feeling that way; trees have such a positive presence in most landscapes, one that’s tied up with the seasons and thus time. Of course, trees are also part of a particularly terrifying history in this country. I was recently surprised to find a list of "hanging trees," in Wikipedia, including those used to murder African-Americans. It was startling and sad to think of how those trees have remained as constant reminders of those horrible events, which for some people, must have been incredibly traumatizing.

Q: Trees can represent so many things. Related to your point about history: time, relationships, family, divorce, race, and identity all flow throughout this collection. I found the poems mentioning aloneness especially refreshing for their candid depictions of how it feels, such as the line, “When the lack of company starts to get to me, I take a long walk.” How do you think of these topics in your poems? How do you see them working in Ridiculous Light?

A: I never think of a topic, per se, when I start a new poem. My poems come out of a compulsion to write, to try to capture something I’ve seen or heard or felt. Even when I’m low on inspiration and give myself a prompt, I still begin with something concrete, perhaps the first three objects I see outside my living room window. Before long, of course, my mind starts using those objects as a means of unpacking a particular topic. But the process typically begins with an image.

Q: The experiences of a black woman come up repeatedly, as the speaker mentions “…playing the typical under-employed woman / of African descent” in the poem, “Flick.” How do you view race and racism in these poems?

A: One writes out of lived experience, and as a woman and as a person of color, racism and sexism are the ocean I swim in. But again, my poems begin with the senses, with image. For instance, the poem you’re referencing began with me noticing that an old Hollywood Video had been turned into an urgent care clinic, which felt ironic since, like a lot of lonely, single people, I’d spent quite a few nights roaming the aisles of that Hollywood Video in pain. And yet, I was happy that, through the crafting of the poem, I discovered ways of highlighting, not just the general pitfalls of being single and dating, but of being a black woman who’s single and dating. And in the midst of doing so, to also highlight other issues, like the generations of African-American women who have been not so much unemployed, but "underemployed." The associative form of the poem actually called for that kind of expansion, i.e., leaping from one disparate thought to another.

Q: In addition to moments that feel both frank and reflective, there are striking lines describing “your day-old body” (in “Insomnia”) and “the sky losing its mind” (in “Cliché This”), among others. Another poem, “Aubade,” mentions a “fleeting glimpse of the sublime / in other people’s poetry,” which intrigued me because I kept glimpsing the sublime in your poems. Tell us about your writing process and how you develop these lines.

A: Thank you. When I think of the sublime, I think of being taken out of my ordinary existence if only for a few seconds so I can only hope that I’ve managed to create some of those moments in my own poems. In terms of how one manages to capture an intense moment in a poem, writing is mysterious, but as a poet, you have to trust that if you put in the effort, the words you’re looking for will come. So it begins with trust. Sometimes a line falls in my lap, but not often. Typically, I have to feel my way to it, almost like, say, threading a needle; I keep missing it and missing it until finally, I get close enough that I can pull it through. Another way of saying this, of course, is that I have to constantly revise.

Q: You are both a visual artist and a poet, and this collection has a painting of yours on the cover. Did painting or writing come first for you? How did you decide to pursue degrees in both?

A: I’ve been painting for almost as long as I’ve been writing. I started writing fiction in my twenties, and painting was initially something fun I did when my writing wasn’t going well. By the time I finally realized I wasn’t a very good fiction writer, I’d started taking painting more seriously and was happy to devote myself to it full-time. It wasn’t until I finished art school and started running an art gallery that I discovered poetry. I’m not sure what led me there, but I started reading the Poetry Foundation website during my lunch breaks. That was the beginning. Although, a friend recently reminded me that I used to have "bring your favorite poem" parties at my place, which I’d totally forgotten. And when my mother died, I found a poem in her papers that I’d published in my junior high school newspaper. So maybe I’ve been moving toward poetry all my life without knowing it. Anyway, I pursued graduate degrees, 10 years apart, in first art, then in poetry because I needed teachers and community and time. There’s this idea out there that people are born artists and writers, that we don’t need teachers; that’s not true.

Q: What books and artwork have you not been able to stop thinking about lately?

A: The Carrying by Ada Limon and The Octopus Museum by Brenda Shaughnessy are both on my nightstand; I love their work so I can’t wait to finally have time to dig into their new poems. I just finished Natasha Trethewey’s Monument: Poems New and Selected; it was such a treat to read all my favorites from her previous books as well as her new work, to hear her beautiful, harrowing voice.

The painter I can’t get enough of these days is Deborah Dancy; the conversation she’s having with herself as well as the history of abstract painting is so freaking cool.

Q: As an artist who works in several mediums, do you move between them or focus on one at a time? What are you working on now?

A: I typically go back and forth between the two; that is, I’ll write poems for a couple of weeks, then paint for a couple. Although the truth is, I’m always doing both in my head. Poetry and painting are a kind of spiritual practice for me; they allow me to deepen my experience of myself and the world.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.

Valencia Robin reads at Literati Bookstore on Friday, August 16, at 7 pm.