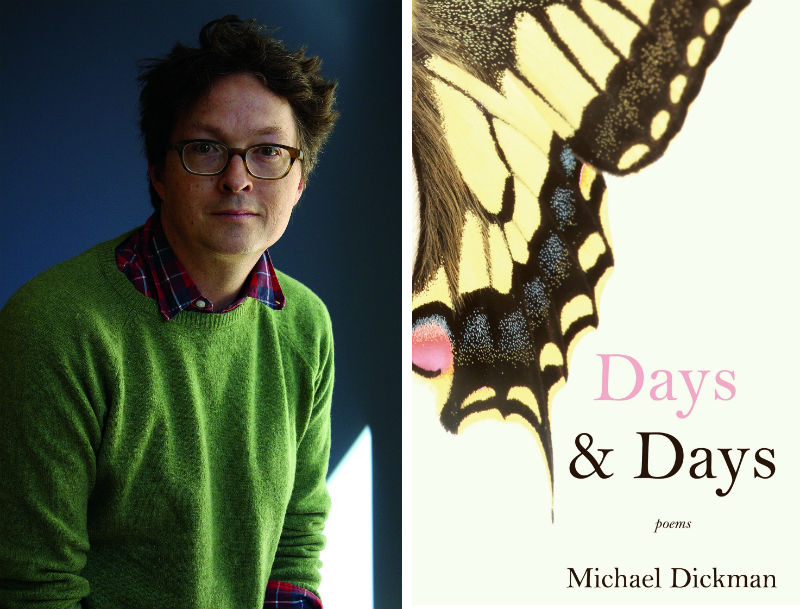

Poet, Princeton lecturer, and former Zingerman's employee Michael Dickman accounts for days line by line in new collection

Days go by in many sorts of ways: hectic, enjoyably, dragging, intensely, calmly, explosively, gratifyingly. They can take on not just one but a range of characteristics. I am convinced that poet Michael Dickman goes through his days attentively if his poems are any indication of how he lives.

Drawing on nature and circumstances, Dickman’s new collection, Days & Days, reveals observations about parenthood, television, love, hotel stays, prescription drugs, and bodies of water. The poems are associative. Lines next to each other may seem unrelated and abstract at times, and then a line a few pages later will relate to a previous thought. The longest poem, “Lakes Rivers Streams,” reads:

This is the earth & sometimes the earth

changes color

Now I remember they were horses mulching the backyard

The horse metaphor for children continues:

My horse kids eat something off the ground I can’t quite make out

and

What should I do with their withers & fetlocks what should I do with

their dressage?

A parade is nice

These lines capture the variety and vicissitudes of days, whether with children or other topics. One wonders if Dickman is constantly jotting down fragments as he goes through his days and later fits them together into cohesive poems.

Formerly of Ann Arbor, Dickman now teaches at Princeton University. He reads at Literati Bookstore on Friday, September 20, at 7 pm. I interviewed him prior for Pulp.

Q: You worked for years at Zingerman’s in Ann Arbor. What brought you to Ann Arbor? Tell us about working for Zingerman’s. Did the job inspire poems?

A: I had moved to Ann Arbor in 2000 with my girlfriend at that time, who was a graduate student at the University of Michigan. I needed a job, a way to contribute financially to the groceries and rent and saw an ad in a local paper that Zingerman’s Deli was hiring. I had never been there before, but I had worked in food service in the Pacific Northwest. So I went to see what it was all about and really was struck by what an amazing place the Deli and Next Door was. I applied and was hired, luckily, by Rodger Bowser, who became a lifelong friend and culinary mentor. I loved the people I worked with and the ingredients we got to use on a daily basis and the fact that it was a creative place. If you wanted to invent a sandwich or salad, add or revise the menu, Rodger was encouraging of that.

Reading about food was a big part of working there as well. Words were as important as sharp knives. Working at the Deli did not inspire poems about working at the Deli, though I did plenty of thinking about poems while cooking. Standing in a freezing kitchen in February while you wait for the stoves to heat up, one’s mind can certainly drift. And so, I did write a lot while I lived in Ann Arbor and worked at the Deli. I went away for poetry school at the University of Texas-Austin’s Michener Center for Writers for three years and then headed straight back to Zingerman’s. I was there in the kitchen peeling a pickled cow’s tongue when I first learned that The New Yorker had accepted a poem of mine. The relationship between food and cooking and poetry is a long and storied one, and I certainly found it to be alive in that kitchen at Zingerman’s Delicatessen.

Q: How did you come to write poetry in the first place?

A: In high school, I had a profound reading experience. A close friend convinced me to buy a copy of Pablo Neruda’s raw and startling book of love poems, The Captain’s Verses. It lay unread in my room for weeks, but finally, I decided to take a look at it, more to impress my friend than anything else. I read it from cover to cover in one sitting, and at the end, I was in tears. That had never happened to me before. I had not known that you could express yourself in that way, and I certainly did not know that you could be a man and express yourself in that way. It was startling. And so, I began writing Neruda-esque rip-offs, until finally simply trying to make a poem that was mine seemed more interesting. I was a sophomore in high school then; I’ve been writing poems ever since.

Q: Since then, you’ve lived around the country, growing up in Portland, Oregon, working in Ann Arbor, studying for your MFA in Texas, and now teaching at the Lewis Center at Princeton University. Your poems are very much about the world around the speaker. How does place influence your writing?

A: Place influences my writing directly, as I think it must anyone. Certainly, wherever I happen to be at the moment -- Portland, Ann Arbor, Princeton -- has some bearing on how I am living my life and what I might be doing with my days. I think it must make a difference if you are looking at, say, trees all day or very tall buildings. The immediate world around me works its way into my poems, little bits and pieces of the day broken off and put into a line. Automatic sprinklers going off, a leaf blower, a child crying upstairs, a phone ringing in the next room. But that is mostly a surface or workaday experience. The place that has a mythic hold on my imagination, mind, and heart, body and all five senses, is the Pacific Northwest. No matter where I am, I am writing from that home place.

Q: You also teach in addition to writing. How does teaching poetry differ from writing it for you?

A: I’m not sure how to answer this. It may be the same difference between talking about swimming and actually swimming. Or talking about eating and really eating. I love doing both. One is sharing and discovering what you are most excited by in the reading and writing of poetry and, through that, developing an intimate relationship with language in the company of smart and curious and excited students. Writing poems, though, is something else altogether. It is an opener. More private. I’m not sure I have the language to describe what writing poems is like.

Q: Let’s talk more about your poems. Your new book, Days & Days, accounts for and reflects on various types of days, such as the poems “Butterfly Days” and “Prescription Days,” among others. Why these particular days? What drew you to categorizing and describing days in this way?

A: In a previous book, Green Migraine, I had written three or so poems, each one the length of a sonnet and each one called “Butterflies.” I liked how it felt to be in these poems, and I like butterflies. I think “Butterfly Days” grew out of wanting to stay in those poems and, at the same time, say something different, do something different. I never have projects. I don’t write toward goals. I am not programmatic. I often think that books that are heavily centered around a project are also deeply conservative, despite their subject matter. Any theme a book of my poems might have feels completely accidental, at least to me. But somehow those three poems, “Butterfly Days,” Prescription Days,” and “Hotel Days,” did float up to the surface. And I have two small children, and small children will force you to notice things you may not have noticed, on a cellular level, from day to day.

Q: Poems in this collection feel very associative as the speaker notices seemingly unconnected things in the environment and life; yet, threads run through the poems in various lines, such as the metaphors involving horses in the poem “Lakes Rivers Streams.” I imagine that the associations do something different in each reader’s mind. How do you approach bringing things that feel disparate together in poems?

A: They don’t feel all that disparate to me. I think our lives, our days, are much more chaotic and jumpy and interesting than we give them credit for. We tend to think, or some of us do anyway, of our lives in a kind of straightforward narrative line. I woke up. I made toast. I drank coffee. But things are much weirder than that. Or much wilder. I write and revise toward some kind of unknown shape and sound and music and image-driven story until it is there in front of me. I never know what it is beforehand. I also want to be encouraging of all emergent language while writing a poem. I want to say yes. These habits might lead to the associative feeling you mention.

Q: Also on the topic of “Lakes Rivers Streams,” it is the longest poem in your collection at 80 pages. How did this poem come together? Did you expect that it would be long as you were writing it, or did it surprise you?

A: I did not think it would be as long as it ended up. I started writing these little seven-line lyric things on the occasional early morning that I had been up before the kids or during my daughter’s nap time. I would have about an hour to write -- that’s all. Just sitting still and listening and following lines or images and seeing where they could go in seven lines. I thought I would just see where they went, and then at some point, it felt like the poem was taking some kind of shape. Messy, and strange, but a shape all the same. It took exactly 12 months to write, from May of 2017 to May of 2018. At some point during that last month, I wrote, “In the morning the kids come running down the stairs” and thought that’s it, the poem is over. The kids are here. It’s time to start the day.

Q: What poets and collections are you reading right now?

A: I am reading the brilliant Karen Solie’s new book, The Caiplie Caves, and all of Les Murray’s poems and Jay Wright’s The Prime Anniversary and Paul Muldoon’s Frolic & Detour and all of Ai’s poems and all of Lucille Clifton’s poems.

Also, though these aren’t poems, Stephen King’s Pet Sematary and Darcey Steinke’s Flash Count Diary: Menopause and the Vindication of Natural Life and Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women and all of August Wilson’s plays.

Q: And the usual ending question: what are you working on next?

A: Poems. Line by line.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.

Michael Dickman reads from "Days & Days" at Literati Bookstore on Friday, September 20, at 7 pm.