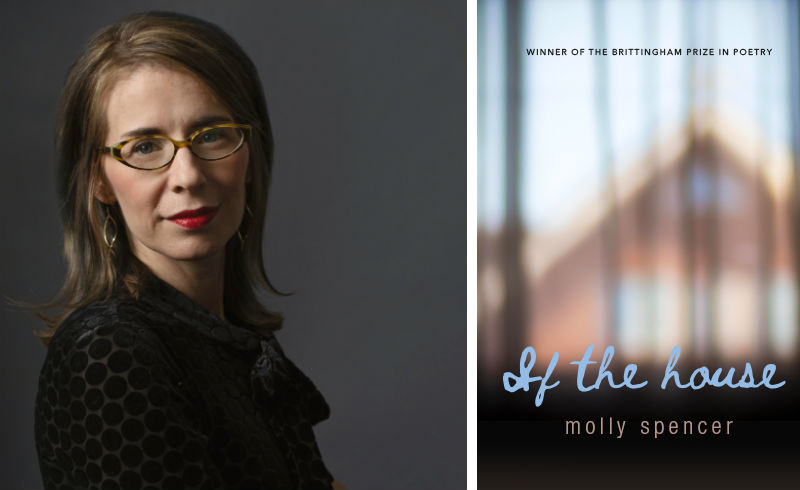

Poet and U-M writing instructor Molly Spencer sees the world "as a collection of thresholds" in her new book, "If the house"

Throughout Molly Spencer’s new book of poetry, If the house, each measured word reveals the intensities and scenes of home, time, and solitary experience amidst people and relationships. In a poem titled “How to Love the New House,” there is a line that answers, “Until you ache with it.” Another poem, “As if life can go on as it has,” includes the sentence, “The earth has all these endings,” and the speaker goes on to share, “I am / in a kitchen’s heavy afternoon / light,” almost implying that the sun could indicate a conclusion.

Perhaps most consistently, the passage of seasons prominently delineates time in If the house. Early on, a stanza depicts time’s effects through apples and squash:

Given time, they will ripen,

grow sweet, become something

for you to get by on.

It seems that time offers sufficient sustenance to keep going and also that time keeps independently moving, resulting in byproducts like sweetening. Later, the lines, “It’s December” and then “October and the birds flock / and rise, whole-cloth” appear in different poems. So months also mark time in this collection, along with other indicators, such as, “My body / adds itself again to the unfolding / rooms of time,” and there are “...other Augusts far / from here, but not so far you can’t / reel them back in....” Each moment is clearly fixed to others by virtue of time being linear, but life in this poetry collection’s world still changes and shifts, showing contrasts to previous points in time to which the speaker remains connected.

While poems generally allow for new and different readings depending on how the reader sees the lines as relating, Spencer’s collection in particular frequently presents alternate ways of looking at poems. In several poems, the phrases, “he says” and “she says,” pepper conversations between a man and woman with no punctuation -- this style adds a fluidity, lack of clarity on who says what, and associative quality that both employs line breaks and embodies the sometimes nonlinear nature of talking as people jump between topics. Reading those conversation poems is fascinating because they feel like a glimpse into a private moment, as well as an informative study of how personal conversations might sound to an outsider.

You could say that this book is about domestic life. You could also say that the collection outlines place and occurrences. You could add that it explores memory, love, and relationships with people and things. More abstractly, though, If the house uncovers the discomforts and comforts of a constantly evolving life and questions what is enough, as

It is not enough to want

to be good. Not enough to wish

I deserved the pitch of a roof overhead....

This question becomes unclear in terms of what enough would be, yet at the end, the collection offers these lines:

The facts of each day come to rest

all around me, fallen,

rust petals of the ditch, lily.

In some ways, the poems suggest that attention and care become what is necessary and what quite possibly has to be enough.

Spencer teaches at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy and is the senior poetry editor at The Rumpus. She reads with guests Donovan Hohn, and Lena Khalaf Tuffaha at Literati Bookstore on Friday, November 1, at 7 pm. I interviewed her beforehand for Pulp.

Q: When and why did you start writing poetry? What was your experience with a low-residency MFA program?

A: Like many writers, I began writing as a child -- probably in grade school. By middle school, I was reading Gwendolyn Brooks and Emily Dickinson and furiously typing up my own poems on my dad’s electric typewriter. Then and now, I think that I write to understand the world, or to try to understand it, at least. And also, to luxuriate in language – its layers and resonances. But I grew up in a very small town, and had no concept or model of what it meant to be a writer, no idea of how to make writing a profession, and in college, I thought I ought to study something practical, something that could get me a good job, so I studied economics, then went to graduate school in public policy. All along, though, I was reading and writing, and eventually, I guess you could say I gave in to my desire to write, to be a writer, and began devoting myself to it seriously around the time my oldest, who is now 18, was born.

I decided to get an MFA several years ago because I felt like I’d taught myself all that I could by reading and writing on my own. By that time, I had three school-age children and a mortgage -- it wasn’t really an option to drop everything and pursue a traditional, on-campus MFA. I chose the Rainier Writing Workshop (RWW) for practical reasons: the schedule seemed the most manageable to me (unlike most low-res MFAs that are two-year programs with two residencies each year, RWW is a three-year program with one residency a year). It was a fabulous experience -- partly because of the faculty members I worked with and the community of writers it gave me, and also because it allowed me to grow as a writer while honoring the realities of my life.

Q: You are both a lecturer at the University of Michigan’s School of Public Policy and poetry editor at The Rumpus. How do you view having both a profession and art? Does poetry contrast, complement, or help you escape your work in academics?

A: I feel incredibly lucky to have both. It happened by accident, mostly -- I mean, I didn’t set out 25 years ago imagining that someday I’d be teaching at a policy school while also living the writing life. I wouldn’t have known to imagine it, but here I am. I think my teaching at the Ford School and my writing life complement and inform each other. The thing that policy folks and poets have in common is that we all care deeply about the world. And we all have to pay close attention to language -- both poems, and the laws and policies that shape our communities and our country, broker in words.

One other thing: on a practical level, it’s much easier to make a living in the policy world than it is as a writer, and I have to be practical -- I have three kids, one of whom is heading to college soon! I do love teaching poetry, as well, though, so I do some private teaching on the side. But I am really grateful to have a profession I enjoy that makes my writing life possible by paying the bills.

Q: How do you write and/or edit your poems? Do you compose them linearly or rearrange lines?

A: My writing begins with reading. I’m not one of those poets who writes a poem every single day, but I do read poetry every single day. And I find that what I’m reading somehow beckons my own words. As I’m reading, I may begin to hear a scrap of language in my mind, or an image or question will occur to me. If that scrap of language, that image, that question keeps recurring, won’t leave me alone, I give in and write a poem. In some ways, the process is mysterious even to me. A big part of my writing process, though, is just listening to whatever language arrives and testing it to see if it endures. If it does, I write it down, and it somehow invites more language to accompany it.

I tend to compose in lines, and in the order the lines arrive. Sometimes, during revision, I’ll rearrange existing lines, but most of my revision process is actually re-drafting: knowing that whatever poem I’m trying to write on isn’t working, and starting over, usually with a phrase or an image that initiated the poem.

Q: The notes in the back of If the house disclose references included from other poems and works. Do these references come to you while writing to include in your poems, or do you write a poem around a borrowed line? Or do you save lines that resonate with you and later insert them in poems as feels fitting?

A: One of the things that I believe about poetry, and art in general, is that it’s a conversation across time. Any artist is trying to express something of human experience cast in a new light, and every artist is influenced by the art they’ve studied. As I said earlier, my poetry is very much rooted in what I’m reading, and I’m very committed to giving credit to those poets whose work helps me get to my own poems, even when our respective poems bear little or no resemblance to each other. So, sometimes it’s a phrase in a poem I’m reading that somehow gets me to a phrase of my own words; or sometimes it’s a borrowed line, yes. Often it’s the rhythm of another poet’s line that I’m after, not necessarily the words. As a reader, I love an extensive notes section that lets me peer -- at least a little bit -- inside the making of a poem; as a poet, I want my readers to know who I’m in conversation with as I write.

Q: Descriptions of morning and evening in various poems in If the house stood out to me because the lines have distinct ways of describing the transition between day and night, such as a “broken dusk”; how “Night begins / to drag over the sky”; and when “another morning will drape / itself over the map.” What draws you to write about these times of day?

A: I think it’s the liminality of dawn and dusk that interests me. The ancient Greeks had two words for time: chronos, which refers to chronological time, clock and calendar time; and kairos, which is something like time-out-of-time, or the appointed time. When we say “the time is ripe” we’re talking about kairos. Those moments of not-quite-day and not-quite-night, those thresholds and our crossing them, seem like kairos time to me, during which consciousness shifts as the natural world reminds us that we are insignificant, ephemeral, and minuscule against the scale of the universe and time. It’s also true that dawn and dusk have such beautiful light, and I’m a sucker for beauty.

Q: Recently I’ve read some collections of poetry that the poet identifies as autobiographical. How do you view your relationship to your poems and their speaker?

A: The poet Marvin Bell talked about this once and said something like “[t]he ‘I’ in the poem is not me but someone who knows a lot about me.” I think this is true for the speaker in my poems, and for the speaker of any poem. The poems in If the house are not autobiographical per se -- that is, with a couple of exceptions, the events of the poems are not based on actual events of my life -- but they do engage with the things I was thinking about, remembering, and living through as I wrote them.

Q: The words “thin” and “skin” appear and reappear in various lines throughout the collection, including “thin silk” and “the truth / of skin.” Snow, ice, and lines -- like the horizon or plot -- also surface repeatedly. Do you think of these recurring things and ideas as themes, as parts of the world that these poems describe, or as something else?

A: Interesting question. I think these words and images, rather than being parts of the world that these poems describe, have more to do with the ways I understand the world, if that makes sense. I perceive the world at the threshold of my body, which is skin. I perceive the world as a collection of thresholds: lines for tracing along and crossing, seasons for crossing through, rooms for entering. The horizon is of interest to me because it’s both vast and unreal -- it’s a line our brains make because we can’t see any farther out -- so for me, the horizon says something about perception and the flaws and limits of perception.

Q: As a poetry editor for The Rumpus, what do you look for in poems?

A: I don’t actually edit poems for The Rumpus. Instead, I edit book reviews and essays on poetry and poetics. It’s not as sexy as curating the original poetry we publish -- it’s like being the guy down the hall in the purchasing department [laughing] -- but literary criticism, which allows us to think about what poetry is and does and can do, and how that happens -- is crucial to my life as poet, and to poetry in general, so I love the work I do there.

Q: What books are you are reading now and/or recommending?

A: I’ve just finished reading Sarah Vap’s Winter: Effulgences & Devotions (Noemi Press) and it floored me. It captures so viscerally what it feels like to be mothering and writing at this moment of human and geologic time. I’m reading Oliver de la Paz’s The Boy in the Labyrinth (University of Akron Press), a poetry collection that engages with parenting neurodiverse children. A poetry collection I’m eagerly awaiting is Jill Osier’s The Solace Is Not the Lullaby, due out in March from Yale University Press.

Q: You also have another new poetry collection, Hinge, forthcoming in 2020. What’s next for you once both of these collections are published?

A: Yes, Hinge will be out from Southern Illinois University Press in about a year. Hinge was actually the first manuscript I wrote but will be my second book, so it’ll be interesting to see those poems -- which I wrote when my kids, who are now all teenagers, were very young -- out in the world.

In terms of what’s next after that, I’m not sure I know. I’m working on some new poems, but it’s not clear to me at this point whether they’ll coalesce into a third manuscript. I have some critical essays I’d like to write, and some already written that I’d like to get published, so I’m working on that. I guess what’s next is what’s always next for me: reading and writing; trying to put language to lived experience. I don’t feel in a hurry to publish another poetry collection, but of course, I hope that happens someday.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.

Molly Spencer reads with guests Donovan Hohn, and Lena Khalaf Tuffaha at Literati Bookstore on Friday, November 1, at 7 pm.