Egg Rolls and Racism: Curtis Chin's memoir recalls growing up in his family's Chinese restaurant in the Cass Corridor

Some lessons arrive early in life and stick with you for years.

For author Curtis Chin, the lesson is “Work hard. Be quiet. Obey your elders.” These instructions become a mantra for Chin as he grows up in his family’s restaurant, Chung’s Cantonese Cuisine, in Detroit. The advice gets him through unfamiliar situations.

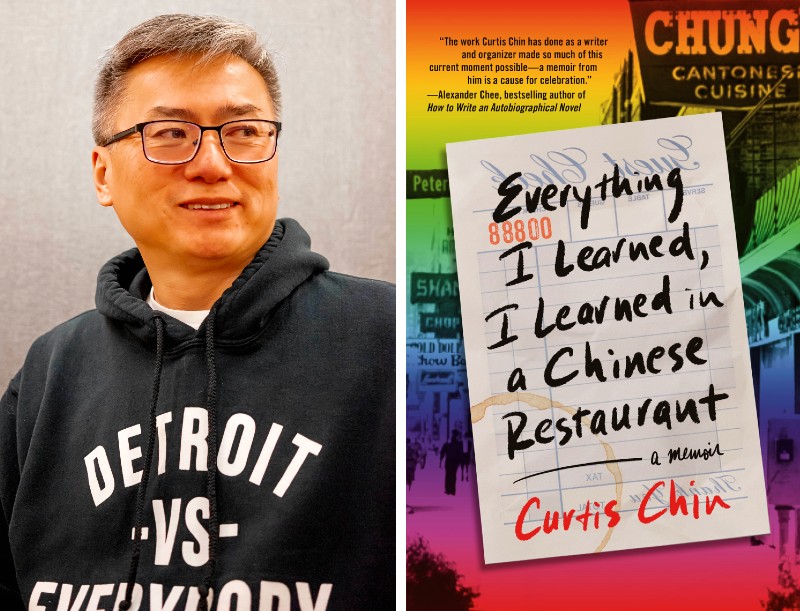

Chin recalls his experiences in his new memoir, Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant. With humor and the kind of introspection that comes with looking back on one’s life, Chin narrates stories from his time in the restaurant and Detroit, as well as his journey to becoming a writer at the University of Michigan. In fact, he worked at Drake's Sandwich Shop as a student. Food, family ties, and Chin’s identity as a gay American-born Chinese serve as throughlines in the book.

The politics and racism of the '80s parallel Chin’s formative years. Chung’s was in the Cass Corridor, a rough area at that time, and its clientele spanned all races and even drew Mayor Coleman Young as a diner. Chin’s father recognized the lessons to be had from talking with customers and brought his sons from the back kitchen into the dining room: “[H]e had really brought us there to discover the outside world, which was sitting right at our tables. All we had to do was listen.”

This environment affected how Chin himself acted, as he writes, “Years later, I learned that what I was doing was called code-switching—consciously speaking and acting differently depending on the background of people around me—but at that age, it was called survival.” In addition to how he behaved, these observations gave Chin an education in how the world and people interact, including “generational wealth and the effects of systematic racism on poverty.”

In addition to the sociopolitical context, Chin outlines the personal pressures that he encountered from family, such as his overbearing grandmother Ngin-Ngin or his parents who wanted him to go to college. There were also pressures from society through stereotypes or gutting comments about Asian Americans or gay people and from himself to be a good son while also following his heart. Chin states in his book, “If a mom or dad didn’t approve of a son’s or daughter’s choice in life, the affection could be lost. I swore that I would never do anything to lose my parents’ love.” Chin found himself torn between his desires, sexual orientation, family connections, and others’ views of him. He explores whether they can be reconciled within the chapters.

As Chin became a man, he found his voice as a writer through successes and setbacks. He was admitted to a competitive creative writing concentration at U-M. This was not without hurdles; one professor critiqued his writing by saying, “This story is too good to be from an undergrad. I want to know where you stole it from.” Her false accusation stung, but Chin is resilient.

Despite these numerous tensions, Chin always returns to the food with mouthwatering descriptions throughout the book. The sections of the book are organized like a menu, starting with the tea and ending with the fortune cookie. Chin describes dishes in great detail as they correspond with his stories. The regular appearances of Chung’s egg rolls with plum sauce, for example, are enough to wish that they were still available for purchase. In another moment:

With some extra time on her hands, my mom decided to make a time-consuming Chinese delicacy: zhu yook bang. The most comforting of comfort food and another of our tastiest off-menu dishes, it featured a steamed pork patty with diced water chestnuts and a cracked egg, the yolk of which blended perfectly with the juices from the pig. She knew how much I loved the dish.

Food was both soothing and inspiring as Chin’s memoir makes clear that the family’s life revolved around it.

Chin will talk with Doris Truong about his book at the Ann Arbor District Library's Downtown location on November 11 at 6:30 pm.

I spoke with Chin about his new book and what it was like to reflect on his formative years.

Q: Tell us about yourself. What have you been up to since you lived in Ann Arbor and attended U-M?

A: After graduating from Michigan, I moved out to New York City to pursue a writing career. Eventually, that took me to Los Angeles where I have been writing and producing film and TV for the past 20 years.

Q: Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant covers your early life in Detroit and Ann Arbor. How did you decide to write a book about this time?

A: The book begins with my great-great-grandfather’s journey from China to Detroit in the late 1800s. I thought it would be a nice bookend to end the book as I am leaving the area to find my own green pastures.

Q: You have written for television and produced social-justice documentaries. How was writing a book similar to or different from film?

A: I think the book draws upon my interests in these subjects. However, writing a memoir requires a lot more introspection and emotion.

Q: Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant candidly describes your path as a gay, American-born Chinese person. How did you decide what to reveal or leave out of the book?

A: Initially, I just wrote down every memory that I thought would be relevant to the book. After landing upon the theme of “for here or to go,” it helped narrow down the stories that needed to be included.

Q: The contrast between society in the 1980s and today’s more accepting world is stark, but we also still have so far to go because racism and homophobia unfortunately linger. Your personal stories are powerful in illustrating how these issues affect people. What do you hope people take from reading your book?

A: My tagline is “Come for the egg rolls and stay for the talk on racism.” I want people to have a good time, but also to think a little about the issues confronting our country.

Q: The descriptions of food in your book are tantalizing. I need to get some egg rolls because you make them sound so delicious! However, it also seems like nothing could taste as good as the now-shuttered Chung’s. Did writing about the food help you recall the stories?

A: I definitely miss the food from our restaurant. I’d love to be able to cook them someday, but I am just not that confident in my abilities.

Q: Your memoir is very rooted in place, first in Detroit and Troy and then in Ann Arbor. Did you rely on your memories or conduct research on any aspects? Why?

A: I think place is so important. It really shapes your identity. Having experienced living in different parts of Southeastern Michigan, I could draw upon those influences in the book. There’s a lot of cultural references, but also Detroit history that is woven into the stories.

Q: What did your work as cofounder and first executive director of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop involve?

A: My work at the Asian American Writers Workshop was more administrative: fundraising, board development, staffing, etc. Writers and artists would come to me with their creative ideas, and it was my job to help make them happen.

Q: What is on your nightstand to read?

A: I’m traveling for the next few months on my book tour, so there’s a big pile that keeps growing.

Q: At the end of the book, I was left wanting more, such as what happened on your next adventure after college. Is there possibly another book in the works? What’s next for you?

A: The book features a structure of three sections, each with eight stories covering elementary/middle school, high school, and college. That’s 24 stories. I have another 20 stories that didn’t make it into the book. I could always release them as a book called Leftovers.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.

Curtis Chin will talk with Doris Truong about "Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant" at AADL’s Downtown location on November 11 at 6:30 pm.