Russell Brakefield's New Poetry Collection, “My Modest Blindness,” Reflects on His Experiences With Keratoconus

Russell Brakefield’s new poetry collection, My Modest Blindness, is both “a telescope of loss” observing how a health condition called keratoconus robs the sense of sight and an exploration of this new state where there are “maybe a million small truths held just out of reach.” Brakefield’s poems take a “reluctant trowel” to excavate this experience and then “step into a life of shadow.” The poet sees familiar life receding and seeks “to reclaim another.”

The book contains six sections, starting with “Paper Boats” which launches the poet unwillingly down this path with keratoconus. The next two sections bear titles suggesting a clinical examination in “Pathology” and a historical approach to eye conditions in “A Brief History of Corrective Technology.” The fourth section called “Ancestors” looks backward and forward, including family, art, and references to film and other mediums. “In Between Worlds” is the penultimate section, in which the poet identifies lessons, such as humility, and in the “Coda,” begins “again to play.”

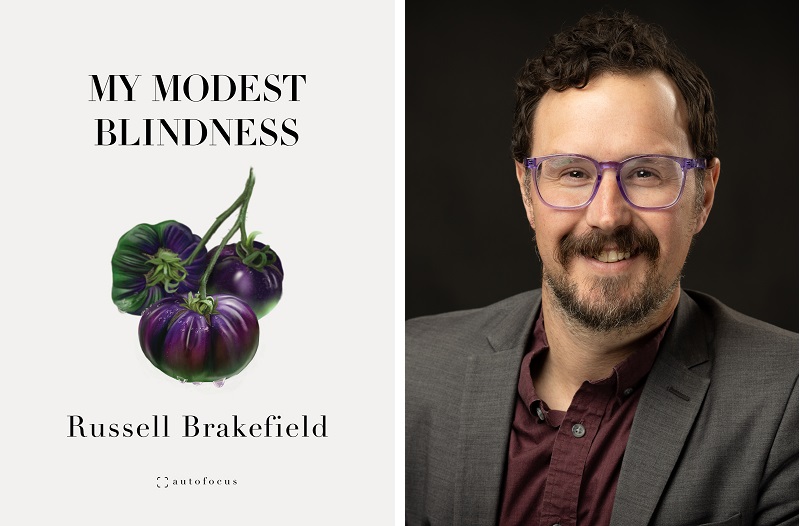

The poems themselves, however, remain untitled, which has the effect of immediate immersion into the poet’s dimming world. The exception to titles, though not exactly formatted like a traditional title, is in the intermittent series of one-stanza poems that consistently start with the word “Entry” and a number in the first line. “Entry #7” describes heirloom tomatoes like those pictured on the front cover:

A tag in the dirt tells

me the varietal is Indigo Apple, though all

year I’ve been calling them Bruises or Savory

Plums or Skyline Just Before Nightfall.

Their purple tomato skin offers a contrast in the garden, a way to relate amidst the darkness.

The poems offer analogies about the condition, such as “I’m a cracked lens a static soaked station transistor broken / I’m a translator with no second language.” Analogies require making associations, and the poet pines how the absence of sight makes this challenging because “what a simple pleasure / to always know where you are in relation to the other / objects in the world.” In this new reality, “the brain is / a camera the eye a lens busted camera shattered lens.” Nevertheless, Brakefield’s questions are obsessed “with finding ways to live.”

As with all ailments, there is a before and an after. Once the news comes, it is always after, and the journey involves simultaneously coping and moving forward. One poem stops to tenderly observe “eons of image like gravel in my hands.” Some of the experiences are collective given that “we are all paragraphs sliding slowly off the page.” So, the poet takes charge: “I write it / down and cut time open.”

Brakefield earned his Master of Fine Arts at the University of Michigan’s Helen Zell Writers’ Program. He is now an assistant professor in the University Writing Program at the University of Denver.

Brakefield and poet Katie Hartsock will read and speak about their books in an event called “Blurry Radiant Landscapes” at the Ann Arbor District Library’s Downtown location in partnership with Literati Bookstore on November 15 at 6:30 pm.

I previously talked with Brakefield about his earlier collection, Field Recordings. In October, we corresponded again about his new book, My Modest Blindness.

Q: The last time we talked was about five years ago. What have you been up to?

A: Quite a bit! My (now) wife and I had just moved to Denver when we last talked. Since then, I’ve gotten a full-time faculty position at the University of Denver, written several books (prose and poetry), adopted several dogs, and found an amazing community here in the West.

Q: You are a teaching professor at the University of Denver. Tell us about what you teach.

A: I teach in the University Writing Program here at the University of Denver. I teach a range of writing classes, with an emphasis on first-year curriculum. I teach a seminar course on the American road trip, a research course focused on environmental justice, a first-year writing course about social protest, as well as creative courses in the Writing Minor. I’ve been really lucky to join such a thoughtful, creative group of writing instructors here at DU and have also found an incredibly robust writing community in the wider Denver area.

Q: How was writing My Modest Blindness unique from composing your other books?

A: This book is, in some ways, much more personal than my other work. It was also a book that took shape rather suddenly, out of notes and materials I have been collecting for years. Though my first book Field Recordings certainly had a unifying theme, this new book really centers on one single subject (the partial loss of my eyesight) and attempts to address that subject from several different angles. This book is also a true sequence of poems, rather than individual poems compiled to form a collection. It was a challenge but also a joy to write in this way; I felt a responsibility to create a sort of arc for the book that would reflect some growth or change in perspective on my part. The publisher, Autofocus Books, endeavors to publish “artful autobiographical writing,” and this really is that, a sort of autobiography of my experience with this eye condition and the ways I’ve learned to reconcile with its effects. This book is also formally much more inventive, or at least different than my previous work. This was a choice I made very intentionally to represent the experiences I was having with my eyesight and the way those experiences have impacted how I see (and write about) the world.

Q: In fact, you have two books that are being published in close succession – My Modest Blindness, which we are talking about in this interview, and Irregular Heartbeats at the Park West early next year. How did it come to be that these poetry collections are being published within months of each other?

A: That’s right! My Modest Blindness was released in October, and my next book will come out with Wayne State University Press in February. It is mostly a coincidence that these two books are coming out around the same time, due in part to publishing schedules and in part to my differences in approach for each of these projects. I have been taking notes and thinking generally about My Modest Blindness for nearly 10 years, whereas I was working on Irregular Heartbeats at the Park West in a very focused way in the three or four years after my first book came out with Wayne State. While Irregular Heartbeats was under editorial review, I went back to my rough sketches for My Modest Blindness, and for whatever reason, when I returned to those notes, the book came together really quickly. There was a sense of urgency when I sat down again to work on it, probably predicated on the changing circumstances with my eyesight at the time and the freedom of mind of having completed the other manuscript. It has been sort of a strange experience if I’m being honest—I’m not actually that prolific, and I generally write rather slowly. But I am so extremely grateful that both books found homes, and I hope that each can have their own lives and reach readers in different and meaningful ways.

Q: My Modest Blindness engages with the condition of keratoconus. You mention your inspiration and writing process in the “Notes and Acknowledgements.” How did you decide to write about this personal condition?

A: I was diagnosed with keratoconus right around the same time I was finishing my MFA in poetry at the University of Michigan. Keratoconus is a degenerative eye condition, which pretty substantially impacts my vision. I’m lucky that my condition was relatively mild to start with and has progressed slowly. However, it has affected my life in many ways and has worsened quite a bit in recent years. Around the same time, I was originally diagnosed, I was taking a course at Michigan with the poet Keith Taylor. He invited students to explore a “gap in knowledge,” so I started researching and writing about poets who have experienced and/or written about loss of sight, vision, and blindness. This is where I first encountered Jorge Louis Borges’ writing about his own blindness. I was also engaging with writers like Audre Lorde, Milton, Lillian Fearing, and of course Homer. I wrote, rather sheepishly, about my own condition for that project, but at the time wasn’t ready to engage fully. I did however start keeping notebooks about my experiences with my vanishing vision and with how it was impacting my worldview and my writing life. Later, when my eye condition began to get significantly worse, I came back to the project and started to give shape to what would eventually become this book. This feels like a cliché when I say it, but this book, and the ideas in this book, really emerged out of necessity. I had to write it but also could only write it when I did.

Q: Recurring short poems throughout the book begin with the word “Entry,” which is followed by a number. The numbers go up to 100 but are not consecutive. Flora and fauna of the West, such as a larch grove and cattle, make appearances. Tell us about these poems.

A: As my condition progressed over the years, and as my eyesight got worse, I started thinking more and more about the role of the visual world in my poetry. One of my biggest fears has been losing my ability to capture the visual world in my poems. My poetry has always been very interested in images, in distinctions, in finding strangeness and beauty by looking deeply at the world as I move through it. I love image/metaphor, and I love making meaning out of the minutiae of everyday experiences. My poems also often tend to be grounded in descriptions of visual landscape. As my vision diminished, I was afraid that I would lose this process. I was afraid with the loss of my vision I would lose the focus of my artistic vision as well. And so, in a sort of act of desperation, I started cataloguing visual images, images I thought were interesting, important, or wonderous. In the book I call this a “catalogue of delights of the visual world in the moments just before it leaves me.” This process ended up becoming an important part of my new writing practice, and I noticed that my altered vision was often offering an opportunity to see things in different ways or to describe things in more abstract or interesting terms on the page. I also found that this catalogue of images served as a unique doorway into a range of subjects and perspectives I don’t think I would have had access to if I was simply sitting down to write a poem without that specific lens. I have notebooks filled with random images, visual and auditory and otherwise, and I included parts of those catalogues in the book. These “entries” perhaps attempt to dramatize my experience in more visceral ways, whereas the other poems in the book speak about my experience more directly.

Q: Mist, fog, shadows, and the like flow within and among the lines throughout this book, too. The poet is not the only one peering through the murk, as there are “all of us searching for a savior or a point of origin all of us burning / faceless effigies walking lost in a wake of smoke.” The cloudiness illustrates the physical experience and also the uncertainty and changes. How did this mist seep into your poems?

A: In his essay on blindness, Borges calls attention to the fact that impaired vision is not, in fact, an experience of darkness or total blackness. It happens differently for everyone, and even with total loss of sight, there are different experiences in terms of color, aura, shadow, etc. For me, my eye condition has produced degrees of blurriness, fog, mist, distortion, and so I felt these were apt metaphors for the way I experience the world. I was also interested, as I’ve noted elsewhere, in reclaiming vision as a metaphor. My experience of the world as one that is distorted or compromised (by pathology, by circumstance, by the systems of oppression and obfuscation we all live through) is not totally unique. I wanted to be able to situate my experience in the larger collective experience of feeling lost, helpless, or undone by forces outside of our control. I think the apparent central subject of this book (my eye condition) also gave me an interesting way to explore all the uncertainties and difficulties and joys of being a writer and a person moving through the world. I used these types of metaphors to explore that and to perhaps reach towards the reader as well, to invite them to consult their own experiences through that lens.

Q: Jorge Luis Borges’ lecture “On Blindness” lends lines, indicated by italics, to your poems. One poem reads, “I hear his voice even after the lectures end: / You must replace the visual world with something else.” For those who have not read the lecture, would you share a brief overview? How did you find this lecture and decide to feature it in your poems?

A: Jorge Luis Borges suffered from a genetic disease that eventually resulted in total blindness. He has written about his blindness in poems and stories, and in Buenos Aires, in 1977 he delivered a lecture titled “On Blindness,” which I first found in the book Seven Nights. I felt like I had stumbled upon a sort of spiritual guide for the experience I was going through in this lecture. In it, Borges speaks about the way his diminishing sight has impacted his writing, but he also does this miraculous thing: he positions blindness not as a deficit or even as a disability but simply as another way of life. Blindness may even have advantages, he argues, for the making of art. “Blindness has not been for me a total misfortune,” he writes. “It should not be seen in a pathetic way. It should be seen as a way of life: one of the styles of living.” This really shaped my thinking about my own condition and guided my writing in the book. I also love writing with other writers, making connections across the canon, and feeling the timeless ties of the literature I love. And so, part of my work for this book was trying to think about what a conversation with Borges might look like, what he would have to say to me about how to proceed in the world even though I was losing my sight. So often we conflate vision and knowledge in problematic ways: someone who is ignorant is “blind” or someone who is closed-minded “can’t see past the end of their nose.” I hate this conflation, and plenty of scholars and artists have done work to reject it. Borges does something else; he leans into this conflation in a way that points out each of our individual bodily experiences as a superpower, as a positive influence for our outlook on the world, as an important aspect of our artistic vision (see there? I did it again!). I wanted to imbue this book (and my life) with the same sort of sensibility. To quote Borges further: “A writer, or any man, must believe that whatever happens to him is an instrument, everything has been given for an end.”

Q: You have lived in Colorado since 2017, and the landscape emerges in your poems. Your earlier collection, Field Recordings, was based in Michigan, and we talked about that in our last interview. Has moving to a new place influenced your writing? Why or why not?

A: Place has always had an important influence in my poetry, though I think it has influenced me differently in this book than in my first book. Field Recordings interrogated issues related to my rural, working-class background in the upper Midwest. And in Field Recordings I was also interested in using folk music as a lens for investigating my own experiences as a person and an artist in these spaces. Those rural Michigan landscapes operated almost as their character in that book, and I still return to those early landscapes often when I’m writing about my younger self. The way I’ve interacted with place has certainly changed as my vision has changed, but my first impulse in writing is still almost always grounded in observations of landscapes and place-based imagery, in image, and in story. In this way, I suppose it makes sense that the landscapes of my new home in the West have also situated itself prominently in my writing. This shows up directly in the “entry” poems you mentioned but also throughout My Modest Blindness.

Q: You have an event called “Blurry Radiant Landscapes” along with poet Katie Hartsock through Literati Bookstore at AADL on November 15. What are you looking forward to about it?

A: I’m really looking forward to hearing Katie read her poems and talk about her book. She is an incredible poet, and her book Wolf Trees brilliantly explores a range of experiences including motherhood and living with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetes is another one of these (sometimes) invisible conditions that can have drastic impacts on how people live their lives. I’m interested to have a conversation with Katie, and with the audience, about the ways we think about and portray illness and disability, particularly through poetry. How can art be both a salve for our suffering and a way to more fully represent and embody our humanity?

Q: What are you reading and recommending?

A: I’ve read so much good poetry this year! I keep returning again and again to the incredible book Bad Hobby by Kathy Fagan. It’s just marvelous. My friend Brandon Som’s brilliant book Tripas deserves all the recent accolades, as does Paisley Rekdal’s inspiring volume West: A Translation. My good friend (and the incredible poet) Franke Varca just introduced me to the work of Bert Meyers, which I can’t believe I’ve never read before; his poems seem to speak directly to me. One weird historical novel I can’t stop talking about right now is North Woods by Daniel Mason.

Q: Where is your writing taking you next?

A: I’m writing new poems now that will hopefully become my next manuscript. These poems seem to be most interested in ecological justice and regenerative futures, especially in the context of the American West. I’m also finishing up a draft of a novel about an ill-fated folk band in the late 2000s and will be looking for agents for that project soon.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.

Russell Brakefield and Katie Hartsock will read and speak about their books during “Blurry Radiant Landscapes” at AADL’s Downtown location in partnership with Literati Bookstore on November 15 at 6:30 pm.