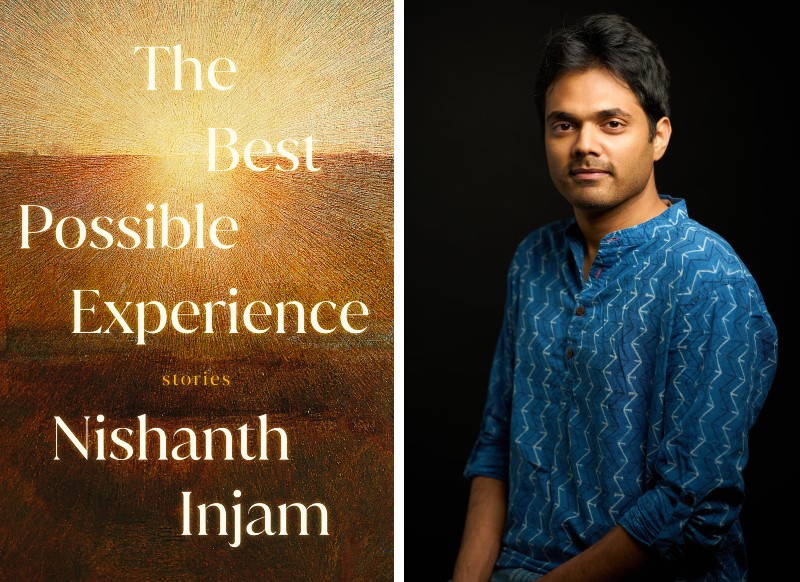

A Search for Meaning: Nishanth Injam's new short-story collection hopes for "The Best Possible Experience"

What is “the best possible experience?” Is it subjective or objective? How does one find it? Does it fulfill or disappoint?

Nishanth Injam’s new short story collection, The Best Possible Experience, seeks to find out whether the best possible experience is everything that it is chalked up to be. The University of Michigan MFA alum’s characters endure losses, yet they nevertheless hold on to their longings. Those longings may or may not be their own, and sometimes their actions mask a deeper desire.

The characters in The Best Possible Experience live in or are from India. They seem to be at odds with something. Here is not there. A significant other or close relative is not present. Despite trying hard, “It wasn’t supposed to have been this way,” says Rafi, who lost his wife, in “The Sea.”

The characters who have left India struggle with being neither at home in the United States nor having a place that feels like their own in India: “Once you go, there’s nowhere to return.” When Sita travels from the U.S. to her village in India to visit her grandfather, Thatha, in “Summers of Waiting,” she reflects on how much time she has there and the way that time passes:

The human brain had a habit of normalizing everything. Time would speed up the next day. Days would devolve into breakfasts, lunches, and dinners. Nights would vanish in sleep. Her twelve days would disintegrate into moments of active consciousness that flickered here and there. But Sita couldn’t keep her eyes open. She went to bed, unable to fight jet lag.

The precious amount of time evaporates quickly. In contrast, Aditya finds his goal to “get a master’s degree as quickly as possible from whichever place took him, find a well-paying tech job, and send money home” not quite so simple in “The Immigrant”. Nothing is easy, and home is so far away because “all journeys had come to resemble one another, the thing uniting them being the distance, all of it farther and farther from where he sat now.” Still, as Sita observes, “Numbers and facts were like potatoes that could be held in one’s hand and examined. Loss and grief weren’t like that.” Emotions are not as tangible or logical.

When the characters find out about the implications of their choices, the regret is strong. The story “Sunday Evening With Ice Cream” finds Aarti and Radha vying for the attention of boys. Yet, upon seeing true love, albeit unable to be satisfied, their new understanding changes everything. Or, the question of whether it is even worth it to travel home haunts a visitor in “The Math of Living:”

My mother has severe bronchitis from years of exposure to heavily polluted air. I’d like to bring her to the country that has me by the collar, I’d like to say to my mother, You gave me breath, and now, I want to help you breathe. None of that is possible without money. And time. And work. And exile. What has exile done? It has taken everything I had in return for the idea of a home far, far away. Home is the sound of a river you are better off keeping at a distance. What else can you do except listen?

The character finds that what is possible is lacking, and “Guilt is what I have left after a lifetime of not acting on my desires.” In trying for more, he ends up with less.

Following his MFA from the Helen Zell Writers’ Program, Injam lives in Illinois. I interviewed him about The Best Possible Experience.

Q: How did you choose to pursue an MFA with the Helen Zell Writers’ Program and live in Ann Arbor?

A: I needed the time to write, and the program had a great reputation. It offered a funded third year without teaching responsibilities. I also wanted to learn from Peter Ho Davies who taught in the program.

Q: Now you are based in Chicago. What have you been up to since your time in Ann Arbor?

A: I published this book! And I’ve been slowly working on a novel while raising a toddler.

Q: Your new short story collection, The Best Possible Experience, was published this last year. How did you go about compiling these stories? What connects these stories?

A: I’d been working on this collection since 2015. Wrote some of them during my time in Ann Arbor and revised the rest. I don’t usually write a story unless I know that it’s worth pursuing, that I can say something new. So, I don’t throw away anything. Luckily, the stories ended up complementing each other. Compiling the collection was a straightforward process of putting them all together. I wanted the collection to have a larger narrative, and I knew I had it. What connects the stories is a search for meaning, whatever shape that might be in. A yearning that never goes away.

Q: The stories in The Best Possible Experience contemplate home, whether it is present or far away or even irrevocably changed from what it was. How did you decide to focus on this concept of home?

A: I don’t think it was an active decision. It’s just one of my central themes. I find the concept of “home” really compelling. Everything I write seems to be tinged with the idea of belonging, of trying to make a home. It’s a register all of us have.

Q: “The Protocol” reads, “If anything, it was his fault—he should never have left India. A country was an empty T seat: you should never leave in search of a better one.” Many of the stories highlight the downsides to going elsewhere in search of a better life. How do you see this relocation showing up in your stories?

A: People might think I’m writing immigrant fiction. I’m on the outside. But I’m also writing about relocation as a question of finding a place to stand on this earth. I think being an adult in this world is like finding yourself in a foreign country. There’s so much resignation, and I’m interested in moving past that state.

Q: Change is not easy for the characters. In “The Immigrant,” Aditya faces challenge after challenge after moving from India to Philadelphia for a degree and work. He learns new rules: “All of these lexicons, he was like a sand particle on a beach, wave after wave rushing at him—there was so much to observe so much to hear so much to know it felt impossible to be still.” How does the form of the short story allow you explore these complexities?

A: I love the short story form. I can take on a voice and be done with it in 20 pages or three. The voice is of course a shortcut to the questions that interest me, questions I can’t parse otherwise.

Q: Some characters find their lives upended in different ways, such as from new knowledge or the loss of a loved one. What do you want readers to learn from the characters’ experiences?

A: I don’t necessarily think about it in terms of learning. I want readers to withhold judgment, to see clearly. I want for them, and for me as well, a restoration of our capacity to yearn. To feel deeply and carry that into our lives.

Q: What is on your stack to read for the new year?

A: Septology by Jon Fosse

The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch

Metamorphoses by Ovid

Signs Preceding The End Of The World by Yuri Herrera

Eagerly waiting for these three 2024 debuts: The Volcano Daughters by Gina Maria Balibrera, Ghostroots by ’Pemi Aguda, The Fertile Earth by Ruthvika Rao.

Q: Are you continuing to write short stories? What is next for you?

A: I’ve more short stories in me but I’m holding off on writing them. I’m currently working on a novel. Can’t say what it’s about yet but I’m enjoying the process of writing it. I want it to be like a mother, full of love.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.