Review: U-M's Guys and Dolls has it all, song, dance, and a big heart

Great theater has the power to magically take us to another place and time and introduce us to the most interesting and colorful people.

This weekend the Power Center is being transformed into Noo Yawk City, circa 1950s. Specifically it's the "devil's own street" Broadway with gamblers, chorus girls, and missionaries out to save their souls in a dynamic, eye-popping production of the beloved musical classic The University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre and Dance production brings it all together: superb singing, beautiful choreography, sharp humor, and a flexible set and lighting that makes good use of the large Power Center stage.

Guys and Dolls is a "musical fable" that makes lovable mugs of the denizens of Broadway based on the streetwise stories of Damon Runyon with a book by Abe Burrows and Jo Swerling and music and lyrics by Frank Loesser. Loesser created one of the finest scores and some of the most loved songs in the Broadway repertoire, drawing on a variety of styles, rhythms, and vocal arrangements. Loesser brought high class music to the lives of the city's "less reputable" residents.

Big musicals are always about strong collaboration. Here director Mark Madam, musical director and conductor Cynthia Kortman Westphal, and choreographer Mara Newbery Greer have put all the pieces together to bring out the best in their student cast.

The story is familiar. Nathan Detroit, proprietor of the "oldest-established, permanent floating crap game" in New York, is having trouble finding a place to host a dice game for a visiting Chicago gambler Big Jule. He is also trying to maintain relations with his "doll" Adelaide, star chanteuse of the Hot Box Nightclub.

Slick, suave, and daring gambler Sky Masterson is back in town and Nathan thinks he's found a way to raise funds to rent a space by betting that babe magnet Masterson will not get a nod from the uptight Sarah Brown of the Save-a-Soul Mission.

This simple plot creates the frame for all that music, complex dance routines, comedy, and romance, and the UM cast seems to be savoring every minute of it.

Will Branner brings a rich baritone and a bit of swagger to Sky. He moves smoothly, as he should, from confirmed playboy to romantically devoted swain. He does a fine job on "Luck Be a Lady."

He meets his match in Solea Pfeiffer's Sarah Brown. As Pfeiffer moves from uptight missionary to a dame in love she handles a sweet transition from operatic soprano to a more modulated popular voice. She is especially effective when Sarah lets her guard down on a trip to devil-may-care Havana (pre Castro). Pfeiffer completely embodies the music and lyrics of "If I Were a Bell," a giddy realization that she's falling in love.

Joseph Sammour plays the less refined street tough Nathan Detroit (as suggested by his name). He fidgets, he worries, he talks tough, but he's really a softie, madly in love with his Miss Adelaide. Sammour is both charming and sly as Nathan but he rises to the occasion on his big musical moment with Adelaide, "Sue Me," which he turns into a warm testimony of his devotion.

Any production of Guys and Dolls hinges on a great Miss Adelaide, the comic spark and the emotional draw of Loesser's songs. Hannah Flam is an outstanding Adelaide: adorable, loud, gawky, and thoroughly convincing. Her musical highlights are many from the Hot Box revue numbers "A Bushel and a Peck" and "Take Back the Mink" to her duet with Pfeiffer on "Marry the Man Today." But the tall, imposing Flam makes her biggest impression on "Adelaide's Lament." She's funny but also poignant when she sings that romantic troubles are enough "to give a person a cold."

The musical really kicks into gear with "Fugue for Tinhorns" in which Nicely-Nicely Johnson, Benny Southside and Rusty Charlie tout contrapuntally why they "have the horse right here." Noah Weisbart as Nicely-Nicely, Wonza Johnson as Benny, and Tyler Leahy as Rusty handle the complex musical and lyrical blending expertly.

Weisbart and Johnson team up for the song "Guys and Dolls" and make like a seasoned vaudeville team, both in fine voice and comic timing. Weisbart is outstanding as he leads the rollicking "Sit Down You're Rockin' the Boat." A nicer Nicely-Nicely couldn't have been cast.

Cameron Jones has a standout moment as Arvide, the older mission leader and father figure for Sarah. Jones sings a tender "More I Can Not Wish You" in a heart-rending tenor voice, each word sharply defined.

Under Westphal's direction the musical numbers are fresh and believable and the orchestra performance is bright and strong while never overpowering the singers.

Greer's choreography is rhythmically precise and effectively handles the numerous styles that Loesser uses from show-biz tap dance to the sensuous Latin movements of Havana to an aggressively stylized crap game. It all works, the student dancers bring rich life to every scene.

Sets by Edward T. Morris and costumes by Jessica Hahn and Michayla Van Treeck capture the period with simplicity but effectively. A special note should be made of Mark Allen Berg's lighting which is effectively used with the choreography to create a sense of drama and punctuate the rhythms.

Hugh Gallagher has written theater and film reviews over a 40-year newspaper career and was most recently managing editor of the Observer & Eccentric Newspapers in suburban Detroit.

Guys and Dolls continues at the Power Center on the U-M main campus at 8 pm on Friday, April 15, and Saturday, April 16, and 2 pm on Sunday, April 17. For ticket information, call 734-764-2538.

Preview: Big Sound Equals Big Fun

**Update 4/18/16 - Big Fun has had to cancel their scheduled appearances for this week. They were intended to appear as part of a panel discussion Monday, April 18 at 7 pm at the AADL, celebrating the 40th anniversary of Eclipse Jazz, and the music of Miles Davis as a prelude to the screening of the film Miles Ahead at the Michigan Theater. They were also scheduled to perform at the Necto in a special pre-screening reception on Thursday, April 21 at approximately 6 pm. This piece has been edited to reflect the cancellation of these performances.**

The baby boomer generation discovered jazz in the late sixties primarily because rock bands of the day incorporated elements like horn sections, the Hammond B-3 organ, hand percussion, Eastern Indian instruments, and funky rhythms into popular music.

Miles Davis became the pivot point in the contemporary jazz of the day, conversely influenced by Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, and Sly Stone. To reach a wider audience, Davis employed fresh-thinking younger musicians to create groundbreaking jazz fusion music that revolutionized how people thought about jazz; to its detriment for some, but ear opening for many others.

The local band Big Fun is now reintroducing this music to the boomers, and giving young listeners a taste of what this style of jazz still represents. Though a scene in the jazz rock music still very much exists and is technologically evolving, Big Fun stays true to the original concept.

Named after a Miles Davis album of the same name, Big Fun runs the gamut of the music the famed trumpeter created from the late sixties up to the mid-to-late seventies. They are recreating those period pieces from recordings like In A Silent Way, A Tribute To Jack Johnson, the quintessential Bitches Brew, and On The Corner.

Increasing their footprint slowly but surely over the past three years, Big Fun was born out of a concept from music instructors at the University of Michigan who saw a need for this kind of jazz filling a void. Trumpeter Mark Kirschenmann and keyboardist Steven Rush sport plenty of credentials as instructors and performers, but thought it was time to team up and give the public music that influenced their thinking as young players.

Kirschenmann has directed the U-M Creative Arts Orchestra for close to a decade. His electronically driven horn sound employs all the modern laptop, digital pedal, and looped sounds possible, but without losing the soul of his instrument. His style is much more earthy than alien, although deep labyrinth excursions are not beyond his purview. He has also been heard with E3Q featuring his wife, the innovative cellist Katri Ervamaa and percussionist Mike Gould, and with the Jon Hassell-influenced ensemble Electrosonic.

Steven Rush is one of our most ambitious local musical heroes. He directs the Digital Music Program at U-M, leads the band Quartex for Sunday evening worship services at the Canterbury House, and presents various electronic and world music sessions. Deeply into Eastern Indian vocal and percussion, he is equally influenced by Brian Eno, Sun Ra, Robert Ashley, Cecil Taylor, Phillip Glass, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Morton Subotnick, John Coltrane and Blue Gene Tyranny. His personality is as freewheeling as his imagination.

Big Fun has performed at the Canterbury House, appeared during the 2015 Edgefest at the Kerrytown Concert House and recently at Encore Records. They also played the recently renovated Residential College in the famed Keene East Quad Amphitheatre, the building where Kirschenmann teaches regularly. It is also the venue where Eclipse Jazz used to host their legendary “Bright Moments” series of innovative creative improvised concerts.

As a witness to the East Quad performance, it’s easy to say Big Fun pulls no punches regarding the authenticity of the music they are portraying. With healthy doses of improvisation, Kirschenmann and Rush stretch out the music without breaking it. Electric bass guitarist Tim Flood pushes with band with ostinato pulses and a powerful persona that belies his smaller, slight build – he is at the center of driving this locomotive.

Brothers Jeremy and Jonathan Edwards do not so much work in tandem as much as they fulfill crucial roles. Electric guitarist Jonathan has the John McLaughlin sound of the era down to a science. He fills in cracks and enhances the overall sound portrait. Drummer Jeremy can be serene and understated, whip up a whirlwind, play deep pocket grooves or anything in between. Tenor or soprano saxophonist Patrick Booth and hand percussionist Dan Piccolo fill roles held in the Davis bands by David Liebman and Steve Grossman, or ex-Ann Arborite the late Jumma Santos and Badal Roy respectively. Their ethnic underpinnings are as important as Ravi Shankar’s contributions to The Beatles.

Michael G. Nastos is a veteran radio broadcaster, local music journalist, and event promoter/producer. He is on the Board of Directors for the Michigan Jazz Festival, votes in the annual Detroit Music Awards and Down Beat Magazine, NPR Music and El Intruso Critics Polls, and writes monthly for Hot House Magazine in New York City.

Review: Starling Electric Makes a Welcome Return With Electric Company

It’s been a while since the world has heard from Ann Arbor’s foremost purveyors of throwback power-pop, Starling Electric. Originating in 1997 as frontman and songwriter Caleb Dillon’s solo project, Starling eventually grew into a full-fledged band, releasing debut album Clouded Staircase in 2006. The band’s psych-tinged jangle-pop drew accolades from national notables like Guided By Voices and the Posies, and Starling became something of a live staple in Ann Arbor and Ypsi. But the band essentially disappeared from the public eye in 2014, when Dillon left Ann Arbor to travel the country for a bit. Fortunately, however, Dillon has returned to Michigan. And with his return comes the long-awaited release of a new Starling record, Electric Company, which has been in the works since 2010.

From track one of Electric Company, it’s an immediate relief to have Starling back in action. Album opener “No Clear Winner” announces itself with the sound of a needle drop and four blaring, distorted guitar chords backed by John Fossum’s majestic drums. Dillon structures the main body of the song in classic Pixies fashion. A quiet verse backed by acoustic guitar and synth accents repeatedly builds to a driving, anthemic chorus. “I don’t know what I control / I don’t know what I can hold,” Dillon sings, articulating themes of uncertainty that have the slightly more graceful feel of willing surrender when backed with music this contagiously bombastic. Dillon cheekily describes the album as “powerless pop,” and the wordplay fits.

Elsewhere, “Permanent Vacation” will burrow itself right into your eardrum and refuse to vacate your brain within five seconds of deploying its simple, catchy opening rhythm guitar riff. If there’s a single on the album, this is it; the bright, polished production and chug-a-lugging rhythm make it one of those songs that demand to be blasted with the windows down on a warm-weather road trip. Another highlight, “Jailbird Joey,” embraces somewhat sludgier production, with Christian Blackmore Anderson’s lumbering bass dominating in the mix. Dillon particularly shows his talent for orchestration on the propulsive closer “Start Again,” which interweaves trumpet, piano, mellotron-generated woodwinds, and some jazzy guitar lines to gorgeous effect.

The centerpiece of the album–both figuratively and literally, at track eight of 16–is “Jesus Loves the Byrds,” a brief but stunning tribute to one of Dillon’s foremost musical influences. The instrumentation on the downtempo tune is simple, but a wistful acoustic guitar arrangement and the quintet’s lush harmony backup vocals make a stellar combination. As Dillon drops lyrical references to “Eight Miles High” and “Turn! Turn! Turn!” (and likely makes a cheeky reference to the Byrds’ cover of “The Christian Life” in the title), it’s easy to slip into the same reverent, borderline-religious mood with which Dillon seems to approach the Byrds.

However, outside of that one unabashed paean to Starling’s influences, Dillon doesn’t wear his muses on his sleeve as much as usual on Electric Company. Where Clouded Staircase so often sounded like a mixture of lost tracks from the Byrds and Guided By Voices themselves, on Electric Company Dillon has developed a clearer authorial voice. He still loves the Byrds’ riffs, the Zombies’ chamber-pop arrangements, the Beach Boys’ harmonies, and Guided By Voices’ maddeningly succinct lo-fi pop genius. But on Electric Company Dillon synthesizes those top-flight guiding lights into something that’s more distinctly his own. It’ll be fascinating to see where he goes next, but hopefully the wait will be less than a decade this time.

Patrick Dunn is an Ann Arbor-based freelance writer whose work appears regularly in the Detroit News, the Ann Arbor Observer, and other local publications. He prefers his pop with at least a little jangle in it.

Electric Company will be available April 15 on Starling Electric’s Bandcamp and major streaming services.

Review: Banff Mountain Film Festival at the Michigan Theater

For the first time ever in Ann Arbor, the annual Banff Mountain Film Festival sold out. It’s not surprising for the festival to sell out in places like Denver or Salt Lake City, with populations of over a million people, but in Ann Arbor there are usually plenty of seats. Not so this year, as 1,650 people filled the Michigan Theater’s main auditorium Sunday night, eager to view the breathtaking selection of films that comprise the festival.

Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival, named for the national park in Canada that hosts it and for The Banff Centre, is a celebration of stories about profound journeys, unexpected adventures, and ground-breaking expeditions. The main event takes place over nine days in Canada, but then select films from the festival go on world tour. Ann Arbor has been lucky enough to be a stop on the tour for many years now. The three-and-a-half hour event features a dozen films of various lengths along with a raffle and an intermission where attendees can peruse booths set up by sponsors of the event and learn more about the festival itself. I’ve gone to the festival for the past five years and the films are always a breath of fresh air in the dreary days of April: from mountain biking to base jumping to heli-skiing to rock climbing to white water rafting, the scenery shown is stunning, the stories told are amazing, and the physical prowess required to do the things captured on film is unbelievable. I leave feeling inspired, relaxed, and with many new travel destinations on my list each year.

This year’s tour opened with The Important Places, a film by Forest Woodward that juxtaposed his father’s aging with his own move away from their home in Colorado to the city. Ultimately, Forest and his dad recreate a rafting trip on the Colorado River that his father had taken 30 years before, in an attempt to reconnect: with each other, with the land, and—for Forest’s father—with his younger self.

In the 5-minute film DarkLight mountain biking at night was made even more amazing by neon lights emphasizing the silhouettes of the bikers, and of the dust they kicked up as they sped across rock outcroppings. The lighthearted film Paradise Waits featured two phenomenal skiers showing off their skills in Wyoming and Alaska while Girls Just Wanna Have Fun blared in the background.

The feature film of the evening was Across the Sky, the story of rock climbers Tommy Caldwell and Alex Honnold, the first people to complete the Fitz Traverse in Patagonia, Argentina in one go. It won the award for Best Film on Mountain Climbing at the festival this year, and it truly was an incredible story. The two men spent almost a month in Patagonia before their hike, waiting for a weather window to open up so that they could attempt the Traverse. Skilled as they were, journeys such as the one they completed always come with unexpected twists and turns, and this one was no different. From gale-force winds to ice-coated handholds, their trip was as much a feat of mental strength as it was of physical. Caldwell and Honnold’s senses of humor and positive outlooks were not only amusing throughout the film, but inspirational to me after it ended, too.

The highlight of the second half of the show was Eclipse, a multifaceted film about a group of “eclipse-chasers” seeking the perfect photograph. Photographer Reuben Krabbe had had a vision of capturing a skier in front of an eclipse for years and knew that such a shot was a once in a lifetime chance. As the eclipse neared, he and a team of guides and professional skiers headed up to the Arctic, pursuing what seemed to be an impossible dream. For Krabbe to get the shot, not only did he have to find a spot from which to shoot that would work, but the weather had to be clear so that the eclipse could be seen and so the skiers could ski safely—and the weather is not usually clear in March in the Arctic. The shot that he ultimately captures is worth the weeks spent huddled in igloos, battling frigid winds, and rescuing sunken snowmobiles. The film won Best Snow Sports Film at the festival this year.

The festival concluded with a 60-second parody film: an advertisement for Nature Rx, the cure for irritability, boredom, and apathy, which gave many audience members a good chuckle. The Banff Film Festival will be back in Ann Arbor next April and, if this year is any indication, buy your tickets to this delightful event in advance!

Elizabeth Pearce is a Library Technician at the Ann Arbor District Library and would love to go mountain climbing in Patagonia, but never wants to heli-ski.

Review: Sci-Fi Film 'Midnight Special' Is as Subtle as It Is Breathtaking

The highly unconventional sci-fi film Midnight Special opened in most theaters nationwide this past weekend, coinciding with the opening of another highly unconventional sci-fi film, the ultraviolent “first-person shooter” Hardcore Henry. The two films could hardly have been marketed more differently. Hardcore Henry has been widely promoted, preceded by opening-night “Ultimate Fan Events” (can a movie no one has seen yet even have ultimate fans?), while Midnight Special has hardly been marketed at all. The Henry marketing team seems out to convince the world that the next cult classic is upon us. This may well be true; I haven’t seen it yet. And although I expect to have a blast when I do, I doubt extremely that it will even begin to hold a candle to the singularly awe-inspiring experience writer-director Jeff Nichols has crafted in Midnight Special.

The film follows a father, Roy (Michael Shannon), and his son, Alton (Jaeden Lieberher), who possesses bizarre powers. The boy can communicate with electronics in eerie ways and occasionally undergoes episodes during which his eyes glow and he communicates mysterious information to those who gaze back at him. However, due to his condition he can’t be outside during the daylight, leading Roy and his companion Lucas (Joel Edgerton) to transport Alton only by night. The already harrowing situation is compounded by the fact that our protagonists are on the run–from the FBI, the NSA, and a Mennonite-esque religious sect who consider Alton the imminent instrument of their salvation.

The less said about the film’s plot, beyond the above summary, the better – and to some degree, even that brief description almost gives too much away. That’s because one of the key drivers behind Nichols’ story is uncertainty. We’re thrown into the narrative and allowed to figure things out on our own. There is exposition, but it’s doled out slowly and naturally as the characters converse. We’re often forced to draw our own conclusions in the moment until a better answer comes along, both about smaller plot concerns as well as the overarching question of whether Alton is an alien, a religious savior, or just a freak.

However, thanks to Nichols’ excellent direction of a strong cast, the nature of the relationships between the characters is never in question. Shannon, best known for colorful performances in films like Revolutionary Road, Man of Steel, and Nichols’ own Take Shelter, here underplays to extraordinary effect. Roy’s all-consuming love for Alton is right there in Shannon’s eyes from frame one, to the extent that Shannon probably could have made this movie work just fine without a word of dialogue. Lieberher gives an excellent performance, precocious by the nature of his character but never showy or unnatural. Edgerton and particularly Kirsten Dunst are also terrific in their supporting roles. Everyone in the film is cast in a resolutely unglamorous role, forced to prioritize emotion over ego, and they rise to the challenge to tell a powerful story.

“Unglamorous” is a good word to describe Nichols’ vision overall. He summons the steamy Texas and Louisiana backwaters the characters speed through with such accuracy one can almost feel the humidity in the air. His pacing and tone are perfectly pitched, masterfully juggling the tension of the chase with graceful scenes of familial tenderness among the protagonists. And – oh yes – this is a sci-fi movie, and there are some spine-tingling supernatural moments rendered with judicious use of CGI. But unlike Christopher Nolan, whose genre films effectively crank both family drama and visual spectacle to the max, Nichols dials back and lets the audience lean in a bit to embrace a sense of wonder instead of bombarding us with emotional and sensual stimulus.

The cumulative effect is extraordinary, building to a protracted, breathtakingly beautiful climax that brought tears to the eyes of even this usually stoic moviegoer. One wonders what Nichols might do with a budget bigger than Midnight Special’s modest $18 million, but hopefully the director’s marvelous restraint isn’t just a product of financial necessity. However, the film's relatively low profile compared to Hardcore Henry, its main genre competitor this weekend, is likely a more direct result of budgeting. And that’s a shame, because it seems likely that Midnight Special will remain a lot more compelling a decade or two from now than Henry’s admittedly audacious technological gimmick. Midnight Special’s greatest strength is its humility, its unassuming and unpretentious genius. Here’s hoping that doesn’t hold it back from well-deserved recognition as one of 2016’s very best films.

Patrick Dunn is an Ann Arbor-based freelance writer whose work appears regularly in the Detroit News, the Ann Arbor Observer, and other local publications. He can be heard most Friday mornings at 8:40 am on the Martin Bandyke morning program on Ann Arbor's 107one.

"Midnight Special" is now playing in select theaters including Rave Cinemas Ann Arbor and Quality 16. Check theater's websites for showtimes.

Review: Winteractive: The Art of Video Games

Despite what Roger Ebert once said, video games can be art. Art is anything that conveys a universal truth and, as psychologist Daniel J. Levity says, “if successful, will continue to move and to touch people even as contexts, societies, and cultures change.” The exhibit Winteractive: The Art of Video Games, currently on display in the University of Michigan Hatcher Gallery, has some great examples of games that do just that.

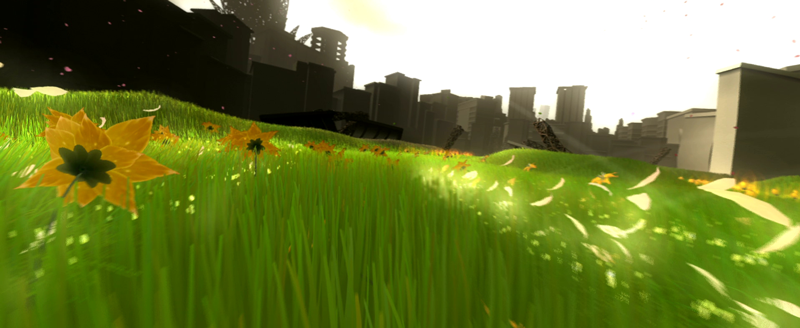

In Flower, you are the wind, controlling the movement of a single flower petal through the air. Though no words are involved, the game follows a narrative arc that explores finding balance between nature and a constructed environment.

The Unfinished Swan is an existential exploration into the equivalent of a Jackson Pollock painting. You, as the player, are a young boy chasing after a swan who has wandered out of a painting and into a surreal, unfinished kingdom. The game begins in a completely white space where you get to throw paint to reveal the world around you and venture into the unknown.

Passage is a metaphor for the human condition that explores the poetry of experiences and consequences. Each play-through is a five minute "poem" in which you get to experience an entire human lifespan. Passage asks you to choose which goals are most important and demonstrates how pursuing one goal can make the pursuit of others more difficult. Do you seek companionship, treasure, distance? It's up to you, and your early choices alter your eventual experience.

Winteractive is a hands-on exhibition. Eight games in total are set up for you to play at demo stations throughout the Hatcher Graduate Library Gallery.

Video games, just like writing and painting, are a creative medium. Early language existed as a means to communicate danger. Writing originated as bookkeeping. Painting began as an attempt to capture the reality of nature as seen by the human eye. It takes time to change the perception of an audience – sometimes many generations' worth.

Games can educate and often provide a means to escape your reality, but some can also touch your heart and connect you to the universe. Some games are art, as this exhibition clearly demonstrates.

Anne Drozd is a Production Librarian at AADL.

Winteractive: The Art of Video Games is on display through Friday, April 15 at the University of Michigan Hatcher Graduate Library Gallery, located at 913 S. University Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109. This exhibit was a collaboration between the Ann Arbor District Library and the University of Michigan Library Computer & Video Game Archive.

Review: Give Three Cheers, and One Cheer More for UMGASS's Production of the Pinafore

OK, so, H.M.S. Pinafore means a lot to me. I was into theater a bunch when I was a kid, and as a sophomore in high school in Overland Park, Kansas, I found myself in the role of Ralph Rackstraw, and found my crush in the role of Josephine. Or maybe she became my crush because she was in the role of Josephine. The 80s are a little blurry these days, but I definitely remember singing Twist & Shout on a parade float. Suffice it to say, this show gives me the FEELS, and I know it like the back of my hand.

So, naturally, I approach many modern stagings of H.M.S. Pinafore with a bit of trepidation. I love the of-the-momentness of Gilbert & Sullivan, and that moment was not the Roaring 20s, or the South Pacific circa 1943, or on the bridge of a Starship, or any such nonsense. I get it, the temptation of a stunty slant on such an endlessly reheated work can be irresistible for cast and crew alike, but I'm in the audience, damme, and I'm here to see something authentic-ish!

Which is why I was so delighted by what must have been the University of Michigan Gilbert & Sullivan Society's umpteenth staging of H.M.S. Pinafore. With the exception of a small amount of clever, harmless nonsense tacked on to the beginning of each act, this was a wonderfully authentic production, with very strong leads and a talented chorus, put on at a rollicking pace with a pit orchestra spilling over into the aisles of the Lydia Mendelssohn Theater.

Tom Cilluffo delivers an outstanding performance as Ralph Rackstraw. I really appreciate that UMGASS does not amplify their cast, and Cilluffo fills the hall with his mastery of the role, going for and easily nailing the high notes that even some professionals pass up. He's very funny as well, in a role that often gets played overly earnestly by high school sophomores in Kansas.

Adina Triolo as Josephine is even more excellent, anchoring the production with her talent and poise, balancing Josephine's ethereal solos with a gift for mugging as appropriate. Gilbert & Sullivan's original productions were famous for eschewing the stilted, heavily-stylized delivery of their time in favor of remarkably natural performances, and Triolo continues that tradition while still shining as a virtuoso in a challenging role. Yeah, so she also looks quite a bit like my high school crush. No, you have goosebumps.

Phillip Rhodes as Captain Corcoran does a great job with some of the show's best songs, and plays especially well with Don Regan, who is refined and funny as Sir Joseph. I will say I was disappointed by Sir Joseph's straightforward aristocratic costume; his frippery is usually a highlight of Pinafore Productions. However, Regan gets big bonus points for pronouncing "clerk" as "clark" to properly rhyme with "mark"; this is a Gilbert & Sullivan shibboleth; those who miss this rhyme should be put to death.

Andrew Burgmayer did an admirable job as Dick Deadeye, physically inhabiting the role thoroughly enough to make it a surprise when he shrugged it off for curtain call. I do wish I could have heard him a bit better, but it's a tough range. He and Rhodes did a wonderful job on "Kind Captain, I've Important Information," perhaps the only duet ever written about a torture implement.

Lee Vahlsing held the entire show together as Bill Bobstay, a role with a lot of exposition to deliver and did an outstanding job on "He is an Englishman." Vahlsing and Cilluffo were joined by U-M freshman and impressive bass Natan Zamansky on the challenging a capella sections of "A British Tar", and they nailed this song where community productions often run aground.

Lori Gould was a perfect Buttercup, adding some great asides to the role, and the director did a careful job to set up Meredith Kelly's Cousin Hebe as a love interest for Sir Joseph, which often seems to come out of nowhere once the social order inevitably goes all topsy-turvy. Surely that's not a spoiler, seeing as how THIS SHOW PREMIERED IN 1878.

All the sailors and sisters and cousins and aunts are well-rehearsed and the choreography is delightful, with some very clever and funny twists without falling into gimmickry.

My only real disappointment with this show was a truly nerdy nitpick; there's a short exchange between Sir Joseph and Hebe near the end that was a recitative in the early productions, but then became spoken dialogue. I don't care if the spoken version has been canon for 130 of the work's 138 years; I love that recitative and would have been thrilled to hear it! What do Gilbert & Sullivan know about Gilbert & Sullivan anyway?

And along those lines, there's an alternate ending where Sullivan added a chorus of "Rule, Britannia" to celebrate Queen Victoria's Jubilee. I love UMGASS's tradition of opening the show with having the audience stand and sing "God Save the Queen," and I was hoping they'd go with the Imperial ending! As you can see, these are very important concerns.

This is a fun, polished, and refreshingly straightforward production of one of the greatest works of musical theater, and a entertaining evening for total fo'c'sle noobs as well as for hopeless Savoy-savvy fussbudgets like me. Whether this is your first experience on the Saucy Ship or your hundredth, you're sure to enjoy the efforts of these safeguards of our nation. Congrats to cast and crew, and thanks for a trip down memory lane.

Eli Neiburger is Deputy Director of the Ann Arbor District Library and had no business being cast as Ralph Rackstraw in high school. Love levels all ranks, but it does not level them as much as that.

UMGASS presents H.M.S. Pinafore continues April 8, 9, and 10 at the Lydia Mendelssohn Theater. Ticket sales have closed online, but tickets will still be available for purchase at the Box Office.

Review: Molière's medical satire gets lost in a carnival

The University of Michigan production of Molière's The Imaginary Invalid is giddy, bawdy, extremely noisy, and intermittently funny.

Translator James Magruder sought to recreate the theatrical carnival that would have surrounded and interrupted Molière's play when it was first produced in 1673, but in the process Molière's satire takes a back seat and a beating. Director Daniel Cantor takes Magruder's ideas and adds on some of his own. Molière is a mix of pratfalls and comic repartee but the physical action here is often aimless and drags on and the verbal wit is often lost in the noise.

The production seems less like a carnival than a mishmash of Ionesco and Beckett, fart jokes raised to art by Aristophanes and beloved by 12-year-olds everywhere, English music hall and French chanteuses and even a Saturday Night Live skit.

The set design by Vincent Mountain seems to borrow a bit from Chaplin's factory scene in Modern Times or maybe from Fritz Lang's Metropolis as a way to emphasize constant motion, and every once in a while explodes in bubbles. The costumes are not time specific and range from Molière's day to the early 20th Century. The Entr'acte Company wear form fitting suits that would work just as well in a Star Trek play.

The high point of the production is one of the interludes developed by Cantor and the company. The comedy here is quick-footed, makes good use of modern day references, and cheerfully involves the audience. A talented actor named Caleb Foote delivers the goods, dressed as part clown, part busker serenading his beloved. Foote knows how to grab an audience and hold them for dear life. He makes the best of the free form material with a good singing voice and lively banter.

The cast of the central play is fine. Jesse Aaronson gets to ham it up as Argan, the titled imaginary invalid. He moans, groans, and makes body noises as an insufferable hypochondriac. Argan does battle with his impertinent servant Toinette, played with proper spunk and fire by Kay Kelley. Savannah Crosby plays Argan's older daughter, whom he tries to marry off to a doctor's son so he can be under constant care. She plays the daughter as a pretty 19th Century melodrama maid with a bit of a twinkle.

Also notable are Delaney Moro as Argan's second wife, who plots to take his fortune and sneers appropriately; Brendan Alpiner as the unappealing suitor who reels out memorized spiels of twisted flattery; and Anna Markowitz as the younger daughter, who jostles amusingly with her father, verbally and physically.

But the acrobatics, anachronisms, noise, and busyness drown out the satire that still has some power in our times of medical disasters and cure all fads. A last bit of SNL comedy in the finale makes reference to the presidential campaign at a time when that campaign has turned into dangerous high comedy itself.

Hugh Gallagher has written theater and film reviews over a 40-year newspaper career and was most recently managing editor of the Observer & Eccentric Newspapers in suburban Detroit.

The Imaginary Invalid continues April 2, 8, and 9 at 8 pm, April 3 and 10 at 2 pm, and April 7 at 7:30 p.m. at the Arthur Miller Theatre on the UM North Campus. Tickets are available 9 am to 5 pm at the League Ticket Office within the Michigan League. Order by phone at (734)764-2538.

Review: Larry Cressman's Land Lines

![Shift by Larry Cressman [daylily stalks, graphite, matte medium, glue]](/files/images/pulp/Cressman-Shift-full-view.png)

There’s not much question that someday University of Michigan's emeritus art professor Larry Cressman is going to have his requisite career retrospective—many of them, in fact. But Land Lines at the University of Michigan's Rotunda Gallery is going to have to serve this purpose in the short term.

In this last decade Cressman has held only three local exhibits: Installation Drawings: Dogbane at the U-M East Quad Art Gallery in October 2016; Material Matters in conjunction with ceramicist Susan Crowell at Chelsea’s River Gallery in November 2009; and his Ground Cover/Covering Ground Drawings at the River Gallery in April 2014.

Yet through this period, he’s also had exhibits at the Dennos Museum in Traverse City; the Detroit Institute of Arts; the Hewlett Gallery in Pennsylvania; the Nelson Gallery at the University of California-Davis; the Hill Gallery in Birmingham, MI; and the Richard M. Ross Museum in Ohio.

What these far-flung locales have seen is Cressman’s remarkable work at its minimalist best. His work is comprised of the patient accumulation of hundreds of sticks and twigs in intricate patterns that both delight and defy the viewer’s eye.

It’s one of those modernist artforms that some might say is common enough for anyone to produce—until one actually tries. It becomes apparent soon enough that it takes a thoroughly uncommon attention to detail and a patient aesthetic to piece these works together in their exceptional equilibrium.

These “line drawings” sit somewhere between the three-dimensional form and the nearly infinitesimal two-dimensional line. It is, of course, merely the coarseness of our vision that insists on differentiating between these two dimensions because they are ultimately only a matter of physical degree.

As Cressman says in his artist’s statement to the exhibit:

“A line drawing released from the flatness of paper can exist anywhere. It can venture into our space. It can be kinetic. It can cast its own shadow. The scale of the drawing is only restricted by the architectural space in which it is placed. Work that is temporary allows an additional freedom—any ephemeral material is possible—glass, rubber, electrical wire, plastic, sound, sticks—all materials I have used in my installations over time.

"Most recently I have focused on the use of sticks and twigs—specifically raspberry cane, dogbane, daylily and prairie dock. Gathering this material from fields near my home has become a part of the drawing process. The gestural quality of each plant and the physical nature of the material (density, weight and brittleness) all play a role in my installation drawings as I explore work that is reflective of both the structure and randomness of the environment.”

It’s this drawing with physical form that makes Cressman’s art so uncommonly compelling. The variable line of shadow in conjunction with the often nearly imperceptible flow of air coursing through the site cause the twigs and sticks to sway against the gallery wall—and these investigations into almost indiscernible elevated space make the installation’s stunning forays into multiple dimensionality all the more marvelous.

It’s possible—and indeed preferable—to spend an extended period of time visually tracing Cressman’s line through his varied stems and twigs. Each work features a strikingly different configuration and pattern. What they do share is a focus that makes them readily recognizable as Cressman’s handiwork.

Perhaps the signal artwork of the Rotunda Gallery exhibit is 2015’s magnificently oversized eleven by six by three foot “Shift” installation. This daylily stalk, graphite, matte medium and glue tour de force is an unquestionable masterwork that illustrates Cressman’s art at its most accomplished.

His three-dimensional etched line has been released from its flat surface as modulated diagonal stems protrude from the work’s vertical limbs crafting a heady, disruptive spur to its otherwise sublime symmetry. Each horizontally mounted twig has its own distinct integrity as no two stems exactly resemble each other, even as each has the same individuating appearance.

There is, therefore, an internal harmony to the stray disorderly offshoots in “Shift” that most certainly highlights the similarities and differences of Cressman’s artistry. And it’s this keenly rendered gestalt that rewards our attention.

![Centerline by Larry Cressman [raspberry cane, graphite, matte medium, pins]](/files/images/pulp/Cressman-Centerline.png)

Among other Cressman works, 2015’s “Centerline I” carries this theme with its binary horizontal rows of raspberry cane, graphite, matte medium, and pins hovering against the gallery wall—as opposed to the similar yet overlapping rows of raspberry cane, graphite, matte medium and pins in 2015’s “Centerline.” Cressman carries his folding of materials together in the latter work with as much regularity as in the former strictly constructed drawing.

Each of the 15 Cressman artworks in this exhibit traverses this intricate divide between dimensions—abiding silently both trace and shadow—to draw our attention to the world that lies in-between. His subtle asymmetry keeps us off balance even as the artwork's paradoxical equilibrium holds our attention in balance.

John Carlos Cantú has written extensively on our community's visual arts in a number of different periodicals.

University of Michigan North Campus Research Complex: "Larry Cressman: Land Lines" will run through April 29, 2016. The NCRC Building 18 Rotunda Gallery is located at 2800 Plymouth Road. The NCRC is open Monday-Friday 8 am–6 pm For information, call 734-936-3326.

AAFF Wrap-Up: Dispatches From A First-Timer

The Ann Arbor Film Festival has been a staple of the Ann Arbor arts scene for over half a century. Every year films from around the world are submitted, judged, and shown to hundreds of movie-lovers, and every year I think to myself, “Eh. Maybe I’ll go some other year.”

This year my curiosity finally outweighed my love of staying home and I found myself preparing to attend the 54th Ann Arbor Film Festival.

It’s important to note that I’m an avid movie-goer. I can sit through the goofiest horror movies, the most pointless action movies, and the sappiest romantic comedies, because I just love being at the movies. I like pulling up to the theater on a sunny day and people-watching as I’m waiting in line to buy my ticket. I like sitting in the dark, reading the screen trivia, and waiting for my movie to start. I like theater pretzels and, more importantly, the strange, delicious, scientific mystery that is theater cheese.

My unbelievably low movie standards don’t hurt either. I mean, I liked ALL of those Transformers movies.

But despite my wide-ranging love of cinema, I worried about attending something as serious and prestigious as the AAFF. I worried that it would be dull. I worried that it would full of be odd, deep, confusing films that would be far too avant-garde for my Michael Bay-loving palette. I think I secretly assumed that every movie would basically be like that short film Kirk made on Gilmore Girls. But weirder. And longer. And with fewer fun dance numbers.

But despite my apprehension I desperately wanted to know what this highly-acclaimed festival was all about and, Kirk or no Kirk, the familiar embrace of a movie theater—any movie theater—beckoned.

So I put on my fanciest pants and started at the beginning—the first AAFF event of the year: the Opening Night Reception and Screening.

My first impression of the festival as I walked into the Michigan Theater that night was that it had been silly to think this event wasn’t for me. There were people in their flashiest gowns, the kind you tuck the tag into so you can return it the next day, and there were people who looked like they’d just come from class or work or wandered in off the street, following the delicious scent of buttered popcorn.

This event, it was clear, was for absolutely everyone. This was my first thought as I entered the festival on Tuesday and my last as I left my final screening on Friday night. That feeling of welcome, of variety, of come-as-you-are-and-we-swear-you’ll-find-something-you-like stayed with me throughout the entire festival.

The opening night reception was filled with this open energy and with music that reflected the formal yet fun vibe by mixing classic tunes with, at one point, the jaunty, triumphant notes of the Indiana Jones theme song.

That same energy flowed along with the crowd into the main auditorium as we all took our seats for the first screening of the season, a mix of short films designed to start the festival off with a little bit of everything. Maybe it was the celebratory feel that comes with any opening night or maybe it was the fact that the reception had had an open bar, but the staid, serious atmosphere I'd expected was completely absent. People talked and laughed right up until the show started.

When the first short film ended, the applause was thunderous. When the second film called for the audience to put on those classic, foldable 3D glasses with blue and red lenses, one man shouted “The red goes over the right eye!” and everyone laughed because this was completely wrong and it took half the room a few seconds to realize they’d put their glasses on upside-down. At one point, someone dropped a glass bottle and the entire room listened with barely-contained giggles as the bottle rolled slowly and loudly from the back of the theater’s sloped floor to the front.

The friendly ambiance of opening night left me pleasantly surprised and eager for more, and that eagerness kept me going all the way through Wednesday, which was, if I’m honest, my darkest day at the festival. The first screening I attended that day was News From Home by filmmaker Chantal Akerman and my first feature-length film of the festival. This was a calm, tranquil movie that consisted of lengthy shots of 1970s New York City, as it was when Akerman first moved there from Belgium, with letters from her mother read aloud over (and sometimes under) the bustling street noise.

I went through a few stages of emotion as I watched this film. First I was intrigued, drawn in by the newness of experimental film and fascinated by the idea that these steady, action-less shots could make up an entire movie. Then, I’ll admit, I was bored. I’m a product of the modern age, used to movies laden with special effects and preferably at least one car-chase scene—and I’m used to watching them while I play video games on my phone. So sitting still and watching stillness felt foreign and uncomfortable, sort of like a brand new pair of shoes that I hadn’t quite broken in yet. Then, after a little while, the film seemed to just wash right over me and the steady scenes, the fuzzy crackle of 16mm film, and the quiet tones of Akerman’s soft Belgian accent as she read her mother’s letters became comfortable, almost meditative. Suddenly I was noticing the people in the scenes more, watching their actions and admiring their quintessentially 70s outfits. The moment I stopped resenting the film for not being what I was used to, I could enjoy it for what it was.

Then came the rough patch. My next film screening, which immediately followed News From Home, was another medley of short films, just like the opening night—though this is where all similarities ended. The ten films were all experimental and the entire event was probably my worst-case scenario. I couldn’t grasp the concepts or meanings of any of the films. Some of them contained vaguely familiar imagery cut together in seemingly random order while some seemed like they were intended to be viewed by some alien audience. Some of the films seemed like they were furiously protesting being watched at all. One film was just icons and symbols that flashed bright then dark on the screen to an incredibly loud semi-rhythmic pulsing/pounding noise and by the end it had gotten so aggressive I’d had to plug my ears and close my eyes just to get through it. If ever I have wished for a pair of ruby slippers to click together or a really huge, comedy-sized mallet to clobber myself with, it was then. I left the screening almost afraid to continue on.

But I'd set out to get the full, unadulterated experience of AAFF, and after a night of rest and consideration, I decided that in a festival where there was something for everyone, I was bound to run into some things that weren’t for me.

So, like a glutton for punishment, I returned on Thursday for more—and was incredibly glad that I did. The Carl Bogner Juror Presentation was another screening of short films, this time selected by Bogner himself, a lecturer on experimental film at the University of Wisconsin, and my reaction to this event was a complete turnaround from the day before. I left this screening with a satisfied feeling and a number of favorites, including Je Suis Une Bombe (I Am a Bomb), a video of a woman in a panda suit doing a provocative pole dance and then delivering a passionate speech on feminism and womanhood, and My Parents Read Dreams That I’ve Had About Them, which was literally just that—a deadpan elderly couple, presumably the filmmaker's parents, reading dreams about themselves from pieces of paper being handed to them from off screen. The subtle humor of this last film had the entire audience chuckling.

On Friday I returned for my final and longest day of the festival and was immediately faced with something I hadn’t yet experienced—a genuine film festival disaster. As I sat in my first event of the evening, Chantal Akerman’s D’Est, I noticed a few jumps and blips in the steady, slow-moving footage. This film, like her other work, was filled with scenery, people, and little else, this time taking place in East Germany, Poland, and Russia, and as I sat immersed in the quiet images and endless stream of Cossack hats the screen suddenly went dark. I’ll be honest, there had been a few times during the festival where I’d been unable to distinguish experimental films from technical difficulties, so when the screen blinked to life again I was half-convinced this was actually just some zany film technique. What did I know? Then, minutes later, the image on the screen abruptly burst and melted until all that was left was a blank white screen and then darkness. The unified gasp of the audience as the 16mm film burned under the projector was immense, as if the screening room itself had sucked in a breath.

In the past few days, I’d been part of a lot of communal experiences, and now I'd gotten to be a part of a communal tragedy. The sense of loss was a tangible thing in the room and when the screening was ended early (the film, we were told, had experienced some shrinkage and despite his best efforts, there was nothing the projectionist could do to make it usable) all I could do was turn to the person next to me and go, “Oh no, do you think the film’s okay?” like I was asking about a gravely injured friend. Who knew I could feel such deep concern for something that, days before, I’d been glaring at, wishing it had more quippy one-liners and explosions?

My final event, late that night, was also the absolute pinnacle of the festival for me. I'd spent the entire week looking forward to the Animated Films in Competition, or “animation night” as some of the super-hip festival-goers called it. It didn’t disappoint. Even the strangest films were elevated by beautiful animation and almost all featured equally charming stories. Bottom Feeders, by Matt Reynolds, was a terrifying parody of life, death, and reproduction. Love, by Réka Bucsi, was offbeat and whimsical, featuring hugging humanoid fruits and cute but headless horses. And I felt a special love for Nina Gantz's Edmond, about a sweet little man who feels so strongly that he finds himself devouring the things he loves most—especially the people. It was hands-down the most adorable film about cannibalism I’ve ever seen.

I began AAFF full of worries. Would I like the movies? Would I understand them? Was there anything at all for me at this festival besides, obviously, the many pounds of candy I would inevitably eat?

As it turned out, AAFF took the movie experience I enjoy so much and amplified it to the nth degree. Besides the films themselves, the festival experience was an entirely new beast for me and a remarkably friendly one. Visiting the festival was like being in a popcorn-filled incubator.

After a few days the Michigan Theater, the heart of the festival, began to exert its own gravitational pull and every time I stepped back into the warm lights of the lobby it felt, oddly, like coming home. Each room of the theater became familiar. The backs of peoples’ heads became familiar. “Oh! That’s the hair I saw during yesterday’s film screening,” I would find myself thinking, and then wonder if I was going crazy, and then decide I didn’t care. I became so acquainted with the festival staff and presenters that it was jarring to see them out in the regular world a week later and realize that they didn't know who I was. To them I was just one in a sea of faces, but to me, they were the people who made the announcements and the bad jokes and gave me directions and helped me understand what I was seeing for four days in a row. I grew accustomed to the familiar path from the parking garage to the theater, and from the theater to the neighboring coffee shop, and from the coffee shop to the theater’s screening room. I even sprinted these well-known paths a few (dozen) times when I was nearly (very) late to a screening (or ten).

By the end, AAFF almost had that temporary-home feeling of summer camp, where every face was one I knew and I got to eat as much junk food as I wanted while I wandered around, unfailingly welcome no matter where I was.

Even those films that made me want to pull my hair out and scream seemed to amplify my feelings of success when I found those little theatrical gems that made it all worth it. And besides, when had I ever felt such intense emotion about any movie? Even if it was the all-consuming desire to punch a film right in the face.

It’s tough to say in so few words how I felt about the 54th Ann Arbor Film Festival. It was a strange, funny, boring, exhilarating, fascinating experience. It was a candy-filled, stomach-ache-producing, movie-lover’s-dream experience. It was a fun experience. It was a unique experience.

It was an experience.

Nicole Williams is a Production Librarian at the Ann Arbor District Library and she never thought she'd used the words "adorable" and "cannibalism" in the same sentence. It's been a weird week.