Detroit native and U-M grad Shannon McLeod’s new novella, "Whimsy," tells a different kind of teaching story

Shannon McLeod’s new novella, Whimsy, depicts the perils of those post-college, early career years through the main character for which the book is titled, Whimsy Quinn, who narrates in first person. McLeod is a Detroit native, University of Michigan graduate, and now high school teacher in Virginia.

Whimsy, who got her name because her parents wanted to name her something “that exuded light-heartedness,” works as a middle school teacher in Metro Detroit, copes with the aftermaths of a car accident that she was in, and navigates dating. She tells her story of how she weathers her setbacks, and it becomes clear how they strengthen her. When asked to describe teaching, for instance, Whimsy notes, “I told him I didn’t have much to compare it to, but that it seemed I had less free time and less money than people with other careers.” It is not a glowing description, but she also does not hate it.

Much of the novella situates Whimsy in the classroom. Her profession brings both humor and growth for her. Of running a classroom, she reflects, “I don’t know if you ever recover from the feeling of thirty pairs of eyes staring at you in concert.” That description may sound nightmarish to those of us who do not want to be the center of attention. Yet, Whimsy gets through the first few days of the school year and finds that the students’ levels of observation fade because by "Halloween you’re at the bottom of the students’ lists of interests.” A welcome change.

Teaching is fraught with challenges, though, from getting scolded by an administrator who questions Whimsy’s dedication to catching students passing notes in class, serving as a cafeteria monitor during lunchtime, and socializing with other teachers. Whimsy takes all these situations in stride. When she needs to be away from the classroom, she reveals, “I’d learned quickly not to expect my students to get anything done with a substitute teacher in the room.” A matter-of-fact and responsive character, Whimsy is well-suited to teaching even if she finds herself chagrined at times.

While Whimsy is a self-aware and descriptive narrator, the prose remains sharp and tight. Scenes unfold and shift. The reader sees along with Whimsy what’s really happening, such as at a wedding where Whimsy drinks too much. She attends it with a journalist, Rikesh, who she’s seeing. When she finds herself crying in the bathroom, Rikesh finds her, and Whimsy notes, “He said he would take me home.” Yet, the next sentence shows a different outcome because, she thinks, “I thought he meant he was coming home with me.” The chapter ends there. Disappointment is palpable but not explicitly stated. The endings of all the chapters are poignant, each like a short story coming to a conclusion.

I interviewed McLeod about her novella, participation with the Emerging Writers Workshops at the Ann Arbor District Library, the Wild Onion Novella Contest that Whimsy won, and what’s next.

Kirstin Valdez Quade’s novel "The Five Wounds" expands on her New Yorker-published short story

All of the characters in Kirstin Valdez Quade’s new book, The Five Wounds, are going through something major. While the challenges—teen pregnancy, addiction, cancer—are not uncommon, the ways that each generation of the family handles their circumstances drive the novel.

One character, Angel, has a son at age 15 and quickly becomes aware of how the adults around her do not actually have their lives together. Not only does she have that insight but she also must persevere when she doesn’t get the support that she needs and when she has to instead support the people who are supposed to be helping her.

Yet, Angel proves herself resilient, even from a young age. Her mother, Marissa, informs Angel:

“When you were three you said, ‘Mama, can you tell me all the things I don’t know?’ You were so impatient to learn and make your own way.

Angel smiles. “I don’t remember that.”

Knowing things does not comprise all of Angel’s learning, though. Along the way, she gains wisdom on what people are like and how to interact with them.

Her father, Amadeo, tries and tries to get his life together but keeps succumbing to alcoholism. He acts before he thinks. An accident caused by his carelessness and drinking miraculously results in only minor injuries, but it is the only thing that can convince him to get his life on track, not just for himself but for his family, especially as the whole family dynamic shifts when people enter and exit their lives.

U-M Librarian and AADL Board Member Jamie Vander Broek discusses libraries and "Radical Humility"

How do libraries and the quality of humility go together?

Really well, it turns out.

Jamie Vander Broek unveils this connection in her essay, “A Library Is for You” in Radical Humility, a recent book she co-edited with Rebekah Modrak, a professor in the Stamps School of Art and Design at the University of Michigan.

The Librarian for Art and Design at the University of Michigan Library, Vander Broek outlines how the permission to read whatever you’d like contributes to the humble nature of libraries. In contrast to museums, the people are primary:

Libraries, instead, devote relatively little real estate and resources toward interpreting their collections, instead foregrounding the individual’s experience with the materials. Another person’s ego doesn’t stand in the way of your access to, at our library, a letter handwritten by Galileo and the first cookbook published by an African American. That’s how important you are to us.

Libraries, Vander Broek observes, don’t impose themselves on one’s intellectual adventure or entertainment but rather offer their collections up to people who want to interact with them. There are many ways Vander Broek illustrates this humility, such as noting, “We think of libraries as being about books or even literacy. But they’re really about sharing. They’re about recognizing the value of saving, sharing, and access to society.”

Sharing is caring, many of us have learned from a young age.

Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle Marks National Poetry Month with a Reading and Open Mic

April marks the 25th year of National Poetry Month and Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle will mark the tradition during their monthly reading on April 28 at 7 pm via Zoom (email cwpoetrycircle@gmail.com for the Zoom link).

Poets Shutta Crum, Dana Dever, David Jibson, Joseph Kelty, Loraine Lamey, Gregory Mahr, Edward Morin, and Lissa Perrin will read. An open mic will follow and participants may read their own poem or a favorite poem by another poet.

The Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle has become a home for writers in the greater Ann Arbor area and has been meeting at the Crazy Wisdom Bookstore and Tea Room for about 10 years. The Poetry Circle offers workshops on the second Wednesday of the month and readings on the fourth Wednesday of most months. Currently, several poets, including Jibson, Morin, and Perrin, co-host the group.

Morin is the author of a recent poetry collection, The Bold News of Birdcalls, and gains inspiration from the monthly readings.

Beyond the Birds: Ann Arbor Poet Ed Morin’s "The Bold News of Birdcalls" explores nature, relationships, and work

The Bold News of Birdcalls by Ed Morin is not just about birds. Stories about people, relationships, work, and news occupy his poems. In “Moments Musicaux,” with a dedication to “my sister Audrey,” we read about her birth, marriages, and children. We learn that “Her last words to me were, ‘You’ll look younger if you get your hair cut more often.’ ” Morin sees both the gravity and the humor in his subjects.

Morin’s poems that do focus on nature or birds are not without the poet’s opinion. The poem “Icicles” says, “February is a sallow miser who hoards / what little daylight is left in the world.” Yet the collection is also not without appreciation for the natural world. We see how industrious birds can be, as “Housing for Wrens” offers the lines “along comes the plain-brown-wrappered wren, focused as a meter reader, from yard / to yard appraising birdhouses for nesting.” This poet not only observes the wren but also admits in another poem that:

Julie Babcock's poetry book "Rules for Rearrangement" considers how to carry on after a sudden loss

University of Michigan lecturer Julie Babcock’s recent poetry collection, Rules for Rearrangement, offers a journey to discover what those rules are. The book charts a thorough and far-reaching path through memories and ways to persist when someone has disappeared from one’s life.

The Ann Arbor poet writes, “Everyone is filled with a heavy combination / of blockage and sun.” The obstruction and brightness feel relatable. People have their burdens and their joys.

How might someone go about rearranging both what weighs them down and what buoys them? A stanza in a section called “Arson” asks for the following:

Introduce your new self and explain your need. For instance: I need rules for

rearrangement. For instance: I need to box memories. I need to let my

objects know it’s not them.

For Babcock, it can be a matter of space and objects. That same poem goes on to discuss how “Empty space you uncover will be awkward and shy.” Yet, “Former free space you cover will be angry.” This negotiation illuminates the effort it takes to design spaces, things, and even life differently than what they were before. The poet both rails against and is curious about the things around them and what happens to them.

At the end of the collection when “He returns from the dead so they can discuss Bob Dylan who won the Nobel / prize for literature,” it becomes clear that the rules may be malleable and dependent on how someone approaches them because "'My love,' he says, 'nothing is every one thing.'" Allowing for this multiplicity offers permission for whatever way a person moves forward in the wake of a traumatic event.

I interviewed Babcock about her new book, writing, and novel in the works.

Ann Arbor poet David Jibson on Crazy Wisdom's Poetry Circle, "3rd Wednesday Magazine," and his new book, "Protective Coloration"

It’s well-known that the life of a poet often means being attentive to the world around oneself, seeing parallels between things or living beings and their thoughts, actions, ideas, and values. David Jibson, co-host of the Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle, uncovers these connections throughout the poems in his latest book, Protective Coloration.

The collection’s title is made clear by the poem of the same name, in which a restaurant scene unfolds "with the poet of a certain age, hidden in a corner booth / at the back of the cafe, as quiet as any snowshoe hare, / as still as a heron among the reeds.” There, we see the poet blending in while also taking in the view. Jibson welcomes the reader to join him in seeing striking insights through straightforward language, like the person in “Amy’s Diner” who, while studying the group of men in baseball caps eating the senior special, gets the invitation to “Pull up a chair.”

As people in another poem speculate while preparing and waiting for the arrival of guests, they are “as ready as we’ll ever be, / realizing, now, how much time has passed / since we last dusted in the corners of our lives.” The poems encourage readers to wonder at such things in their own lives.

"Common" People: Ken Meisel examines and celebrates Detroit in his new poetry collection

Detroit is many things to many people. Ken Meisel’s poetry collection Our Common Souls: New & Selected Poems of Detroit outlines these many views through substantial narrative poems that tell stories about the city. The wide-ranging poems examine specific places in the city, people such as its famous musicians, and historical events, including riots, the World Series, and Devil’s Night.

The collection opens with a poem called “Detroit River, January, 1996” that sets the scene for both the book and its perspectives of the city: “River on this coal-blasted shore, / River whose name now starts with a fist, / ends its knees in St. Lawrence.” The poem concludes with an emphasis on the river’s persistence, “River of sunken beer bottles, churn on,” just as the place will carry on through time and everything that has happened there.

The poet peers at the various scenes and underbelly of the city, not overlooking the rough edges, as the poem, “The Gift of the ‘Gratia Creata,’” with a note setting its location in “Hamtramck, MI” declares:

Streets of Your Town: Jeff Vande Zande’s new short story collection focuses on "The Neighborhood Division"

In the neighborhoods, streets, homes, rooms, and basements of author Jeff Vande Zande’s new short story collection, The Neighborhood Division, people live out their lives, their relationships, and their struggles.

Yet, something is always a little unsettled. A car that follows a character on his run, with threats emerging from the driver. The paranoia of being mugged haunts a female character. A man lives shackled in the basement, unbeknownst to the residents. A neighborhood, where no outsiders are supposed to come in, restricts its residents under the guise of making lives better for them.

These stories peer into the disarray of lives behind the four walls that they call home and also question the character’s choices. In the story called “That Which We Are,” a widower reflects on his marriage. His wife used to save money during the year so that she could give it to people in need during the holidays. Yet, he coveted the money for household expenses and splurges, like a television. He reconsiders:

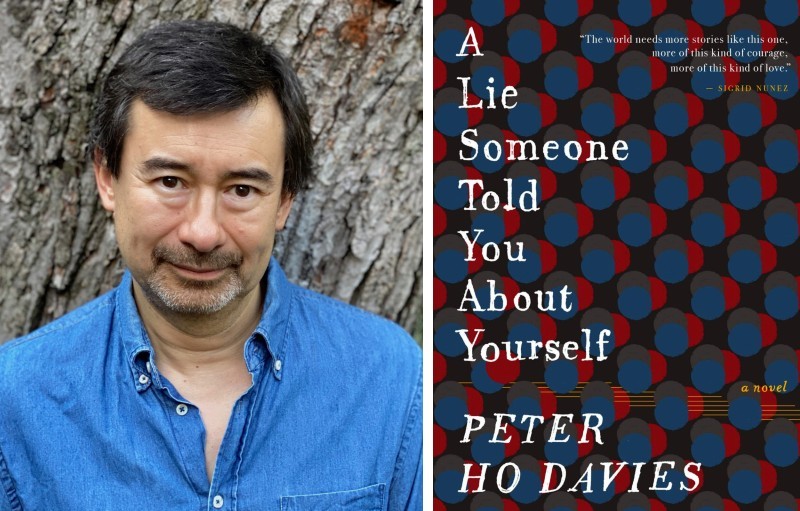

With drama and humor, U-M professor Peter Ho Davies’ new novel follows a family through marriage, pregnancy, and parenting

Family life has come into greater focus this last year during the COVID-19 pandemic. School online. Work from home. Everyone in your immediate family in the same space.

Well beyond our one-year plus some of staying at home during this health crisis, Peter Ho Davies' new novel, A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself, sounds the depths of marriage, parenthood, and family life over many years. Davies, a faculty member at the University of Michigan, does not shy away from the pains and discomforts brought about by such arrangements, but his book also does not bypass the humor and little joys. Told in third person with the characters identified only by their roles of father, mother, and boy, readers may feel like they are on the outside looking in at the characters’ lives. Yet it’s an inside view, like a fly on the wall rather than peering through a window. The narrator homes in on the father’s perspective especially.

Early on, challenges with a first pregnancy force a crushing decision, one that the characters process and must live with for the rest of the book. The fallout and emotions thread throughout the parents’ lives and their reflections on raising their second child. While we learn that the mother is coping through therapy, the father takes another approach of volunteering at an abortion clinic. As the father considers his earlier experience, the narrator describes: