Deep in the Woods: "The Man Beast" is haunted, moody, and anxious

’Tis the season for witches and werewolves.

Also—if the Penny Seats Theatre Company’s production of Joseph Zettelmaier’s The Man Beast is any indication—taxidermy, folklore, French accents, and skullduggery.

Set in 1767 France, The Man Beast unfolds in the secluded home of healer and taxidermist Virginie Allard (Brittany Batell), who’s all too aware of her local reputation as “the witch of the woods.” When fellow outcast Jean Chastel (Jonathan Davidson), injured while hunting a legendarily lethal wild beast, barrels his way into the widow’s workshop, Virginie tends to his wounds, and the two form an uneasy alliance.

Yes, the two become lovers, but they also hatch a plan to collect King Louis XVI’s generous bounty for the beast. Jean notes that there have been no deaths in the nearby village since his run-in with it, so, his argument goes, he may well have succeeded in killing the creature. In the absence of more tangible proof, though, he must travel to a far-off menagerie to procure the carcass of a wild, exotic animal, then bring it back to Virginie to prepare it for a dramatic presentation at court.

The pair’s plot succeeds, but as we all know, money can’t buy happiness, and the bond between the two starts to fray.

Spirit Animal: Theatre Nova’s “Mlima’s Tale" explores the costs of human greed

At the start of Theatre Nova’s production of Lynn Nottage’s Mlima’s Tale, the four-person cast enters in a line, stomping and breathing deeply in unison, mimicking the movements of an elephant.

For that’s what Mlima is.

The old Kenyan “big tusker,” named after the Swahili word for “mountain,” lumbers onto the stage, at which point actor Mike Sandusky (who stands in for Mlima’s tusks, and spirit, through the rest of the play) speaks: of listening to the winds, and the love he feels for his mate, his family.

But it’s not long before Mlima—despite living within a preserve in Kenya—is felled by a poacher’s poison arrow. The animal’s enormous tusks simply garner too much money in the underground ivory trade to be resisted.

Yet getting that money, because poaching is illegal, is a fraught process, so Mlima’s physical death is followed by a fairly predictable chain of interactions between corrupt authorities, smugglers, ship captains, shady art-world dealers and creators, and rich collectors who can’t be bothered with origin stories of “how the ivory gets made,” so to speak.

Previous critics have noted that a point of inspiration for Mlima’s Tale, which premiered in New York in 2018, is Arthur Schnitzler’s La Ronde, which chronicles a linked series of sexual encounters across class boundaries. In Nottage’s piece, we follow the tusks, personified by the ever-looming Sandusky, as they change hands and enrich each person who briefly possesses them.

Make the Trek: "Return to the Forbidden Planet" reimagines "The Tempest" as a campy sci-fi musical

If you’re drawn to the idea of outdoor theater and goofy jukebox musicals that combine elements of Shakespeare and Star Trek—well, Scotty, the Penny Seats Theatre Company is currently staging a show in Ann Arbor's Burns Park that will likely beam you right up.

Return to the Forbidden Planet, by Bob Carlton, first hit London stages in the 1980s, and the show comically reimagines The Tempest with an assist from pop songs of the ‘50s and ‘60s, as well as the campy sci-fi film classic Forbidden Planet (1956).

Captain Tempest, played by a Shatner-esque Cordell Smith, has just launched with his crew (and the audience, otherwise known as the ship’s “passengers”) when the ship, the Albatross, finds itself in a meteor shower—thus cueing up “Great Balls of Fire,” naturally—and then drawn to the planet D’Illyria. There, a long-marooned father and daughter, Doctor Prospero (Will Myers) and Miranda (Ella Ledbetter-Newton), come aboard, as does their robot assistant, Ariel (Allison Megroet). Prospero tells his back story while pleading/singing “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.”

Soon, a huge, tentacled monster attacks the ship; past relationships come to light; schemes are hatched; a love triangle develops; and a grand sacrifice is made—conveyed via cardboard cutouts on sticks, in a kind of whimsical puppet show.

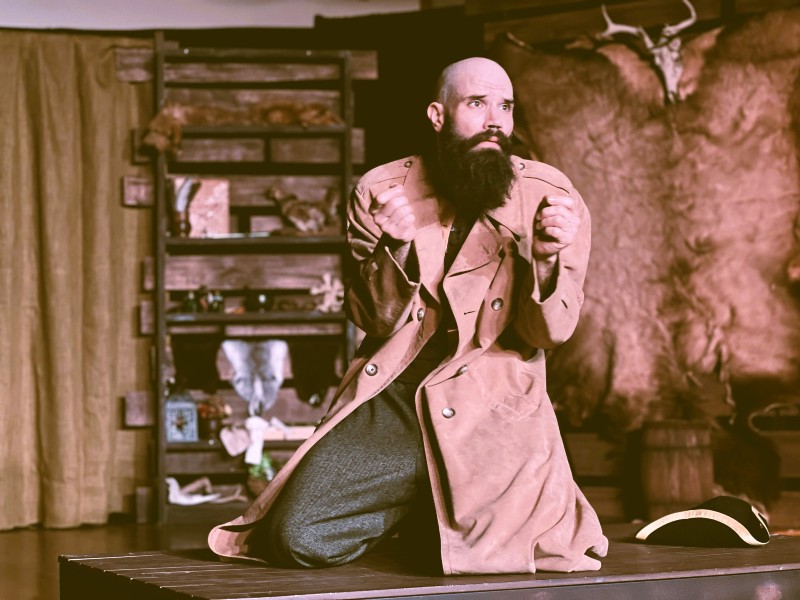

Action Pain-ing: The ghost of painter Jackson Pollock is a conflicted priest's confidant in Theatre NOVA's "SPLATTERED!"

Conventional wisdom teaches us that “art heals,” but not usually via advice from a long-dead painter who suddenly reappears near one of his most famous works.

Nonetheless, this exact situation stands at the heart of Theatre NOVA's world-premiere production of SPLATTERED! by Hal Davis and Carla Milarch, directed by Briana O’Neal.

Set inside New York’s Museum of Modern Art, priest-in-training Justin (Artun Kircali) has snuck away from a wedding reception, with a champagne bottle in hand, to try and pull himself together. He’s just presided over the wedding of his cousin and best friend, Astrid (Marie Muhammad), but we initially don’t know why he’s drinking, cursing, and frantically praying in this gallery while confronting Jackson Pollock’s splatter painting “One: Number 31, 1950.”

But he’s not alone for long: Astrid soon finds him and, eventually, Justin’s old flame Sylvie (Allison Megroet) does, too. Yet it’s the surprise appearance of Pollock’s ghost (Andrew Huff) that provides Justin with an opportunity to unpack the unwieldy emotional baggage he’s carrying, which makes him reconsider his life choices and future.

SPLATTERED! runs a little over an hour, and other than two very brief Sylvie flashbacks, it unfolds in real time and the audience must work hard to piece together what’s happened between these characters in the past. During one early moment of confusion, I had initially guessed that Justin had been hopelessly pining for Astrid. Despite those initial thoughts, this short play doesn’t feel as fleeting as one might expect.

Turn Down for What?: U-M’s production of “Rent” brightened the corners of the play's darker edges

For me, it’s telling that the most moving moment of the University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theatre & Dance’s production of Rent on April 15 came via a curtain call reprise of the show’s iconic song, “Seasons of Love.”

Having taken their bows, the performers slowly clustered together in the middle of the stage, and you could palpably feel the camaraderie among them. That camaraderie didn’t radiate from their characters, but from their real-life experiences as college students, including graduating seniors, who’ve grown close while training and building on shows like this one. The warmth coming from that stage made my hair stand on end.

And in keeping with the program’s esteemed national reputation, the students had hit their marks and their notes (well, most of them) all evening. So why exactly did this polished production feel … well, too buttoned up and tame?

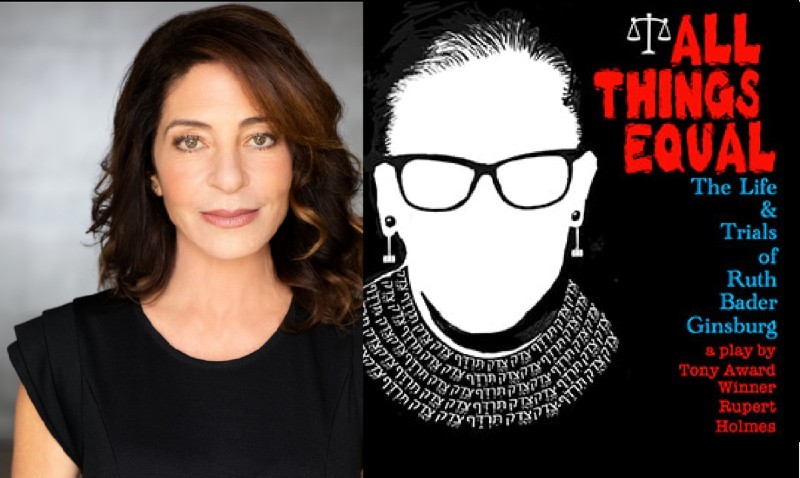

The One-Woman Show “All Things Equal: The Life & Trials of Ruth Bader Ginsburg” Tries to Humanize the Late Supreme Justice

At a 2021 family funeral, one of my aunts, whom I hadn’t seen in decades, immediately guessed which car in the lot was mine: “I saw something with Ruth Bader Ginsburg on it hanging from the rearview, and I said, ‘Dollars to doughnuts, that’s Jennifer’s car.’” (Guilty!)

So, when I arrived at the Michigan Theater on March 14 to see the touring one-woman show All Things Equal: The Life & Trials of Ruth Bader Ginsburg by Rupert Holmes, the deck was already stacked.

But let’s be honest: I was hardly the only fan at the show’s packed Ann Arbor performance. As a feminist icon who arguably did more than anyone to advance women’s legal rights in the 20th century, RBG long ago achieved progressive, secular sainthood.

This ultimately poses a challenge for Holmes and his show, which stars Michelle Azar and is directed by Laley Lippard. How do you bring such a lofty figure down to earth and make her human?

Because frankly, despite Holmes structuring the play as an intimate talk between RBG and a couple of her granddaughter’s young friends in the justice’s chambers, it’s hard to not feel as if we’re prostrating ourselves at the altar of this powerhouse legal mind’s legacy.

Award-winning poet and writer Naomi Shihab Nye set her latest middle-grade-fiction novel, "The Turtle of Michigan," in Ann Arbor

Naomi Shihab Nye is best known for her poetry—she was chancellor of the Academy of American Poets from 2010-15, and the Poetry Foundation’s Young People’s Poet Laureate from 2019-21.

So perhaps it’s no surprise that her newest novel for young readers, 2022's The Turtle of Michigan, is built from subtle, sharply observed moments more than a page-turning plot. (It was recently named a 2023 Michigan Notable Book and will be out in paperback on March 14.)

Set in Ann Arbor—where Nye has taught writing—Turtle begins with eight-year-old Aref (pronounced “R-F”) and his mother taking off in a plane from their homeland, Oman. Aref’s father, having flown to Michigan a few weeks earlier, reunites with them at the Detroit airport, then drives his family to their new, small apartment in Ann Arbor.

Ann Arbor Musical Theater Works Brings The Cult Musical “Moby Dick” to the Children’s Creative Center

What’s weirder than learning that there’s a stage musical adaptation of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick?

Learning there are two, actually, one from 1990 and another from 2019.

And the Moby Dick adaptation that came first, which includes a book by Robert Longden along with music and lyrics by Longden and Hereward Kaye, is the one that local theater artist Ron Baumanis has been jonesing to stage via his company, Ann Arbor Musical Theater Works.

“Whenever I see a show, whether it’s on Broadway or the West End, I always leave thinking, ‘Would I want to do it or not,’” said Baumanis, whose Moby Dick production begins its two-week run February 9 at The Children’s Creative Center.

“When I saw this in the West End, by intermission, I thought, ‘I’ve absolutely got to do this show someday.’ … I was drawn to the weird mix of the show’s all-out hilarious comedy with British pantomime and a lot of burlesque elements.”

Carnal Letters: UMS's No Safety Net series closed with two Rachel Mars plays that explore the expression of desire

If there’s one common thematic thread between British theater artist Rachel Mars’ two shows, Our Carnal Hearts and Your Sexts Are Shit: Older Better Letters, it’s desire and the ways in which it’s expressed.

Both shows wrapped up UMS’s No Safety Net event series with Our Carnal Hearts quickly assuming the feel of a darkly comedic, secular church service complete with a small choir on a bare stage. It takes envy as its focus and explores how our ego reflexively ties itself in knots when a peer or loved one succeeds.

Mars even has the audience say, in unison, “Congratulations! I’m so happy for you!” in the same fake-enthusiastic tone we’ve all employed at one time or another in the interest of appearing like an adult instead of a petulant child.

Presented in the round, Our Carnal Hearts features a different singer—Rhiannon Armstrong, Rebecca Atkinson-Lord, Kelly Burke, and Louise Mothersole—seated in the middle front row of each side. It also combines cheeky musical asides composed and arranged by Mothersole, short audience interactions, and storytelling to plumb the question: why does another’s triumph inevitably make us feel small or less than?

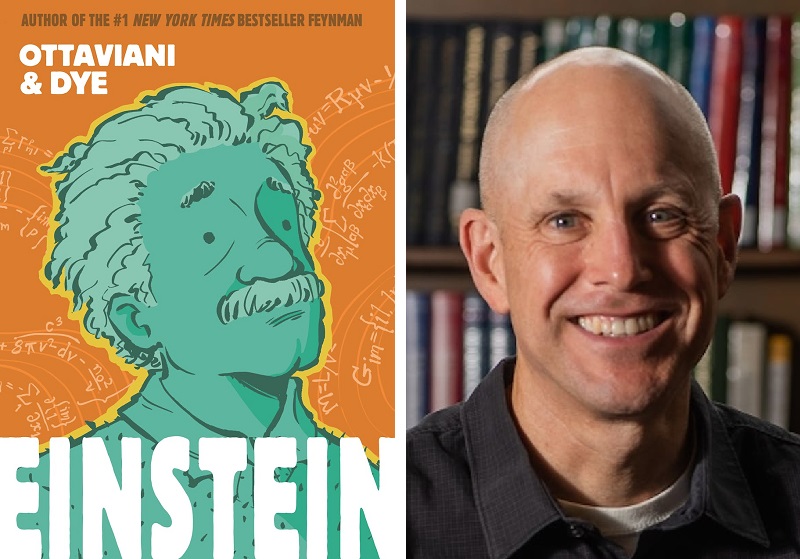

It’s All Relative: Ann Arbor Author Jim Ottaviani Examines Albert Einstein’s Complexity in “Einstein” Graphic Biography

When longtime Ann Arborite Jim Ottaviani decided to write a graphic novel about Albert Einstein with artist Jerel Dye, his first concern was doing the research and trying not to drown in it.

“Deadlines are your pal in this regard, in that, there comes a time when I just have to start writing,” said Ottaviani, author of Einstein and a former nuclear engineer and librarian who previously worked at the University of Michigan.

“I cannot put it off one more day, one more minute. Now, this doesn’t stop me from sometimes thinking, ‘I should just read this one other thing.’ But then you quickly realize there’s a hundred more things you could read, too.”

Ottaviani speaks from experience, having already published similar graphic novels focused on science giants like Stephen Hawking and Richard Feynman. The amount of content available on those icons initially gave him some pause, too, but the resulting books’ success made a convincing case for a project focused on Einstein.

“Everybody knows the name Einstein, and they know that he’s associated with relativity, but few people know why it’s important or what it is,” said Ottaviani. “The hope is that after reading this book, people will at least know what it is and why it’s important to physics. Yes, there are equations in the book, and they’re accurate, but they’re mostly there as set dressing.”