Human Nature: U-M prof Scott Hershovitz talks philosophy with his kids in the book "Nasty, Brutish, and Short"

U-M professor Scott Hershovitz divulges conversations with his two young sons and connects those chats to philosophical concepts in his new book, Nasty, Brutish, and Short: Adventures in Philosophy With My Kids. Among the topics are swearing, sports, racism, and religion.

Hershovitz delves into both questions that his children raise and questions that he and his wife, Julie, face as parents. What makes the book so approachable is that the conversations are set in humous, relatable, day-to-day scenarios. For example, the subject of individual rights emerges when one of the children, Hank, takes ages to decide what to have for lunch after being offered a quesadilla or hamburger:

Shirley Ann Higuchi tells her mother's tale and the bigger story of the Japanese American incarceration during WWII in “Setsuko’s Secret”

Shirley Ann Higuchi illuminates a dark time in U.S. history in her book, Setsuko’s Secret: Heart Mountain and the Legacy of the Japanese American Incarceration.

Through the lens of long unspoken family stories, Higuchi recounts how Japanese Americans were removed from their homes and businesses, then forced to live in one of the 10 concentration camps created during World War II as the result of unfounded security concerns. The memories and trauma of that time are still felt today.

Higuchi, who grew up in Ann Arbor and went to the University of Michigan, will speak about her book at the downtown Ann Arbor District Library on Thursday, September 22, 6:30-7:30 pm. She is a lawyer for the American Psychological Association, a past president of the D.C. Bar, and chair of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, which operates a museum on the site of the former camp.

In Setsuko’s Secret, Higuchi writes of the camp where her parents met, Heart Mountain:

In U-M prof Jacinda Townsend’s “Mother Country,” one woman claims another’s daughter and perpetuates family patterns

“Some people wanted freedom, she thought, and others wanted safety. She’d never find the two in the same place.”

This reflection by the character, Souria, in Mother Country weighs the impossible choices that characters make—or are forced to make. Jacinda Townsend’s new novel examines the repercussions of human trafficking, the implications of family bonds, and cross-continental ties. Townsend is the Helen Zell Visiting Professor in Fiction at the University of Michigan. She is also the author of the novel Saint Monkey.

In Mother Country, when one mother, Souria, loses her child in Marrakech, another woman, Shannon, becomes a mother, gains a daughter, and brings her to Louisville, Kentucky, even though the events leading up to the switch—and also following it—are problem-ridden. Shannon learns, “The right thing never felt like the good thing.”

Souria’s and Shannon’s lives intertwine in ways made more visible by chapters that alternate between narrating their two separate lives. Later on, the perspective of the daughter—once known as Yumni, then as Mardi—emerges, as well as that of Vlad, who is Shannon’s husband. They all are cognizant of their missteps in life, but there is no turning back to change them. For example, Shannon, who often gets high to blunt the lingering pain from her near-fatal car wreck, perceives her flaws, yet cannot remedy them:

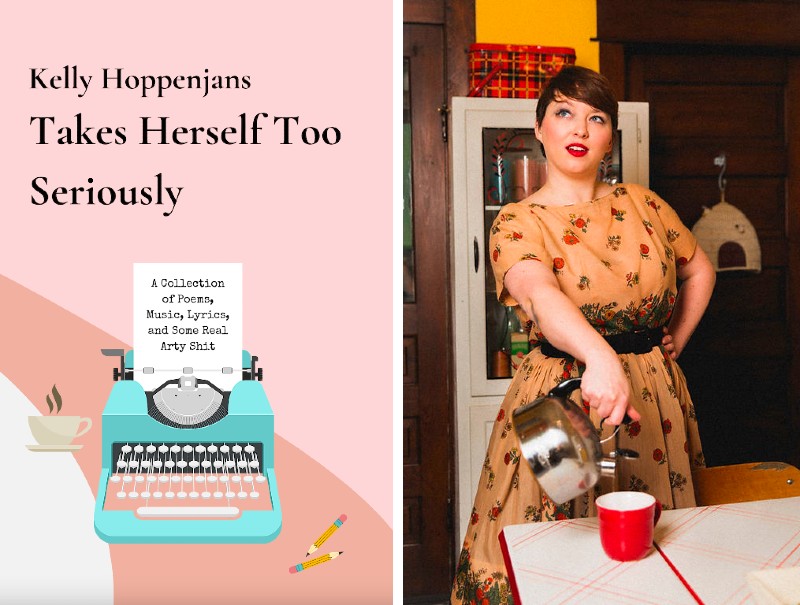

The book “Kelly Hoppenjans Takes Herself Too Seriously” plays with the poetics of the Ann Arbor indie rocker's lyrics

What makes a poem versus a song?

Setting the words to music may be an obvious answer, but the difference between the page and the studio are more complex than that.

In her new book, Kelly Hoppenjans Takes Herself Too Seriously: A Collection of Poems, Music, Lyrics, and Some Real Arty Shit, the indie rock singer-songwriter and graduate student at the University of Michigan draws attention to the lyrics from her recent Can’t Get the Dark Out EP and the divergent forms of poetry and lyrics.

As she told Pulp, “To me, lyrics and poetry are separate forms, and the process for each is quite different.”

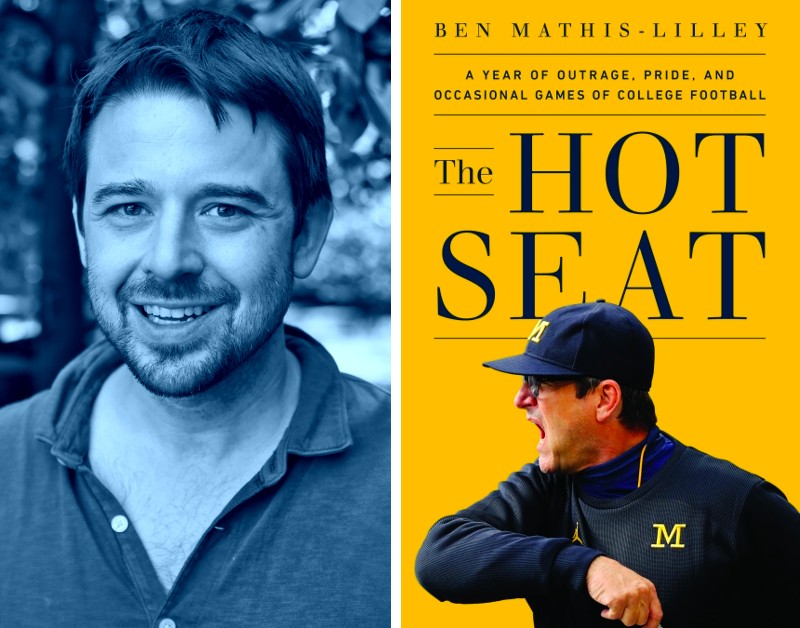

Let's Go Boo: Ben Mathis-Lilley’s witty "The Hot Seat" looks at U-M's 2021 football season from a fan's perspective

One of my favorite parts of Slate senior writer (and rabid longtime Michigan fan) Ben Mathis-Lilley’s new book, The Hot Seat: A Year of Outrage, Pride, and Occasional Games of College Football is a list of fan site comments during U-M’s second game of the 2021 season.

After noting that U-M beat Washington 31-10 that night and that the Wolverines were never, for a second, tied with or losing to the Huskies, Mathis-Lilley shares three and a half pages of these in-the-moment fan perspectives. A few cheery examples: “We’re going to get killed by any offense with a pulse.” “Passing game is atrocious.” “We are not good.”

Of course it’s possible to spot a team’s flaws even when they win, but the pronounced Debbie Downer-ness of this running commentary, shared while a convincing Michigan win on national television is unfolding, makes you wonder: What more could Michigan football fans want? Good lord, would anything make us happy?

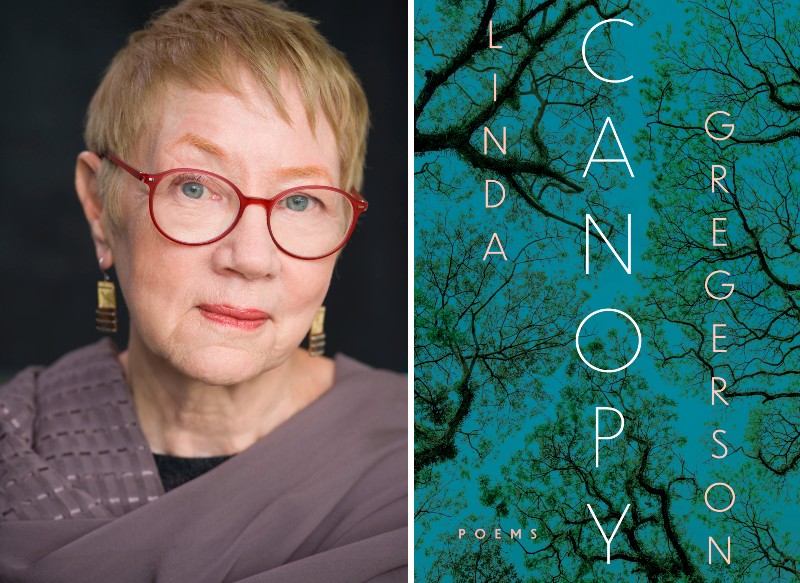

Poet and U-M professor Linda Gregerson’s “Canopy” takes its impetus from gratitude and wonder at the saturating intelligence of the natural world

Linda Gregerson’s new book of poems, Canopy, lifts us to the heights of the treetops and also studies those who toil below where “There’s always a moment before the moment when nothing / is ever the same again.”

The single word “canopy” as the title conjures both a place to aspire to and a boundary delineating human limitations.

Gregerson teaches at the University of Michigan as the Caroline Walker Bynum Distinguished University Professor of English and directs the Helen Zell Writers Program. She is a chancellor emeritus of the Academy of American Poets and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She is the author of seven books of poetry and two books of criticism, and she is the co-editor of one collection of scholarly essays.

Trees, land, and the whole environment figure strongly in these poems in Gregerson’s most recent volume. A painting on a panel of oak allows for the identification of when it was created. When shipping was a dangerous, frequently fatal endeavor on the Great Lakes, a relative several generations back “was among the ones / who did not drown. Who sold his ship / and bought a farm.” The land and the trees bring surety and safety.

The reality on the ground, however, often carries both happiness and disappointment, as a poem asks, “What is it / you love / that has not been ruined because of you.”

Canopy considers not just the ecosystem in which we live but also the current events in it, such as the COVID-19 pandemic threaded through several poems and the murder of George Floyd in “Fragment.” Yet addressing these significant events and issues leave us “bound to act and bound / to be not enough.”

Action is necessary, but the problems are much bigger than any individual.

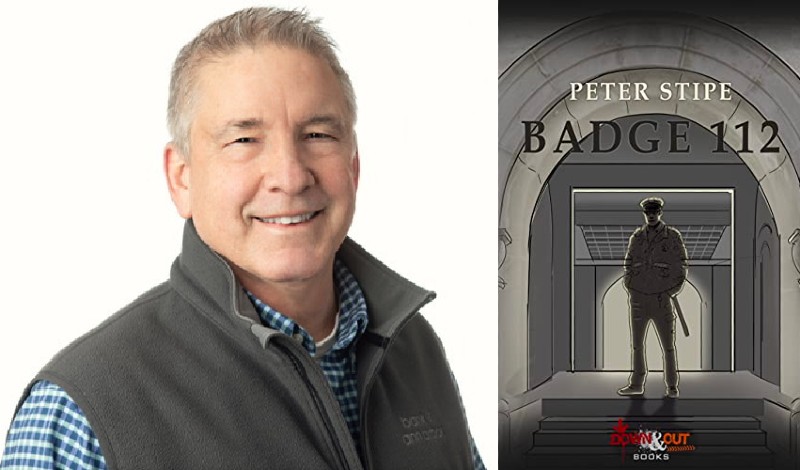

Late-Night Journals: Former Ann Arbor police officer Peter Stipe recalls 18 years on the force in his memoir "Badge 112"

For almost 20 years, Peter Stipe served as a police officer in Ann Arbor. After getting off work late at night, “I would be amped up, go home, and write it all down,” he says. “I wrote a lot of profiles of people at work and their personality quirks.”

The result of all that late-night journaling is now Stipe's memoir, Badge 112.

The idea for putting this writing into a book came from a police inspector Stipe met while visiting his stepbrother: “After hearing me tell stories about my days on the job, he said that I should write a book.”

Stipe began by posting his stories on Facebook.

“I did my test drive there,” he says. “It helped me to figure out how long the stories should be, if I was grabbing people at the beginning, giving a satisfying payoff, and so on.”

He also had people from a variety of backgrounds proofread the material so as “not to err on any sensitive issues.”

Badge 112 is a series of vignettes that allows the reader to drop in and drop out of the book wherever they choose, and Stipe composed his prose in a way inspired by the memoirs of a famous actor.

“David Niven wrote some books about his Hollywood adventures … as a witness to what was going on around him, not as the main character," Stipe says. "I tried to model my writing on that to tell what happened as I witnessed it.”

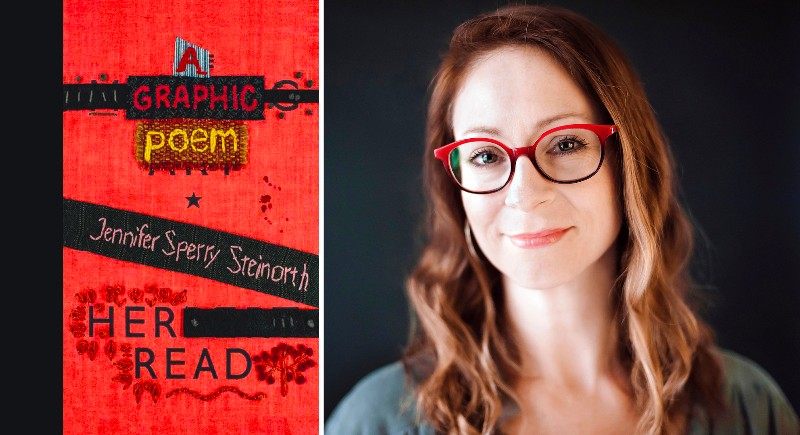

University of Michigan lecturer Jennifer Sperry Steinorth experimented with an erasure project, which became “Her Read: A Graphic Poem”

On the pages of Her Read: A Graphic Poem, author Jennifer Sperry Steinorth finds the imp, ocean, mother, pain, love, religion, and womxn. This book of erasure poetry simultaneously works as a graphic poem with artwork from the original text “radically altered” to make new visuals and word art. The source text, which is The Meaning of Art by Herbert Read, is obscured to varying degrees, sometimes visible very faintly under paint or Wite-Out while at other times incorporated into original artwork.

Pages and lines take on new shapes as the poem is conjured from the existing words and letters. Early on, the poet describes an outlook, noting:

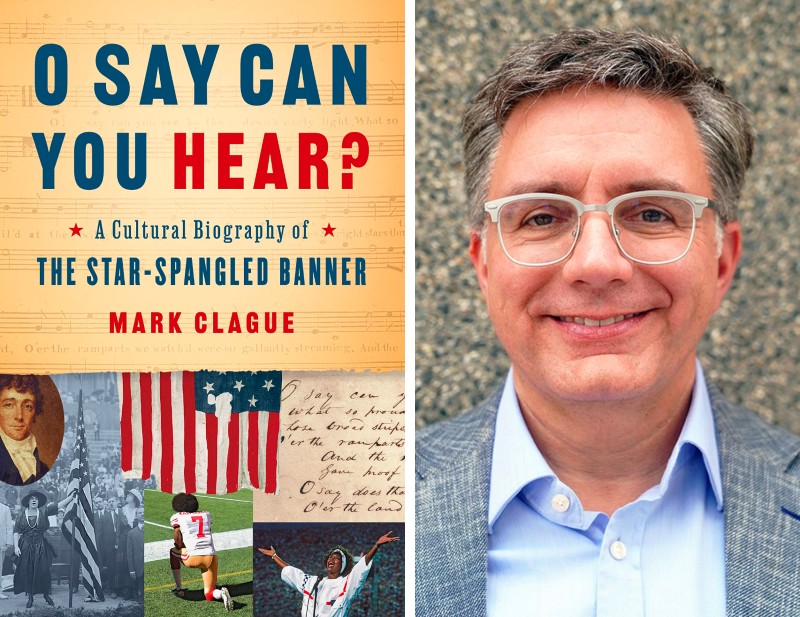

An Ode for the Anthem: Mark Clague’s “O Say Can You Hear? A Cultural Biography of the Star-Spangled Banner”

It seemed a little on the nose to be reading U-M associate professor Mark Clague’s new book, O Say Can You Hear? A Cultural Biography of the Star-Spangled Banner, on the 4th of July—at U-M’s Camp Michigania, no less—but that’s nonetheless when and where I absorbed enough national anthem-themed information to sweep an entire Jeopardy! category.

Indeed, to say Clague is thorough in his research would be a gross understatement.

The Pleasure Principle: The characters in Lydia Conklin’s short story collection, “Rainbow Rainbow,” seek gratification and identity

Characters in Lydia Conklin’s Rainbow Rainbow perch on the precipice of something—a decision, a change, the start or end of a relationship, or even the dangerous cliff above a quarry where people swim and occasionally fatally fall.

Each story in this collection probes personal boundaries and desires to see how far the characters will stretch and when they will run in another direction. Queer, trans, and gender-nonconforming identities inform these stories as well as the book title, which is not only the name one of the story but also an Easter egg in one of the other tales, which reveals the meaning of the appellation Rainbow Rainbow.

Conklin is the Helen Zell Visiting Professor in Fiction at the University of Michigan and they will be an assistant professor of fiction at Vanderbilt University this fall.

Throughout the large—and small—turning points the characters face, they seek out their own needs and endure the pain of loss or the fulfillment gained. When distance grows between lesbian partners living in Wyoming, one of them grasps the extent to which their connection has deteriorated because the other was secretly pursuing her passion. On recognizing the shift, the narrator shares, “The words sent a crack of pain down my neck. We’d drifted so far apart. I’d failed to recognize creative euphoria in my own partner, living beside me in the middle of nowhere for three months. What was wrong with me?”

The beginning of the end had already begun.