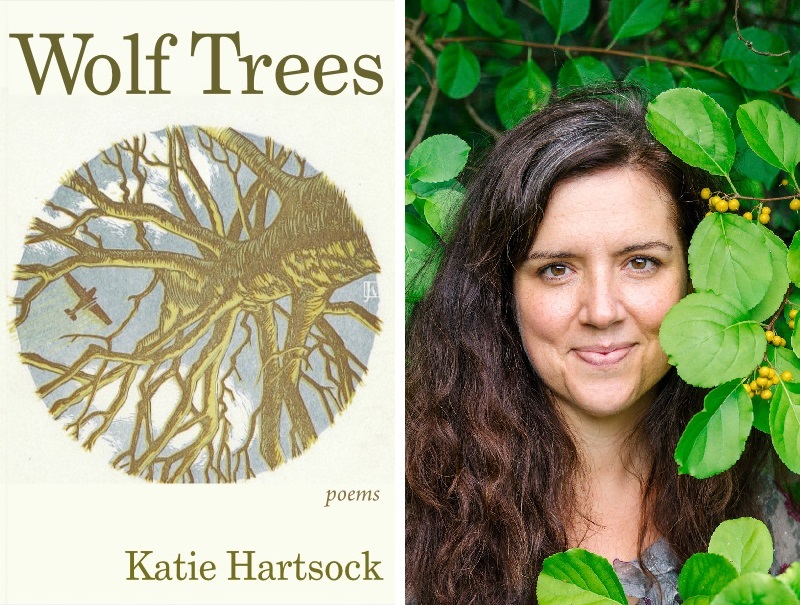

Flow State: Katie Hartsock’s Poems Fluidly Move from One Place to the Next in New "Wolf Trees" Poetry Collection

Katie Hartsock’s poetry collection, Wolf Trees, surveys what persists amidst trials that must be weathered. One poem defines the titular term as, “A tree that is the forest that is / the island.” A wolf tree is also, “A tree to lean / against and think, I’m there.”

Hartsock, a professor at Oakland University, connects the mundane and discouraging aspects of one’s personal and family life to the natural world and also to different points in time. In the poem “Decent Seas,” the setting is a Chicago harbor. The poet instructs us to, “Think of a desire turned into a satisfaction turned into a joy / turned into a joke. That’s how to name your boat.” Whether the topic is boats, local parks, wolf trees, art, or Greek mythology, Hartsock has, “my gaze trained / on earth’s colors as they shift, / ready for invention.” The poet’s attention to nature leads the reader to new associations and even new ways of being in this world.

Hartsock’s poems take sweeping journeys through the woods, as “you see something and think of something else.” The poems’ lines make sharp observations about having children, managing a chronic health condition, and traversing both regular days and other countries. “It’s all a little Sisyphean,” Hartsock writes.

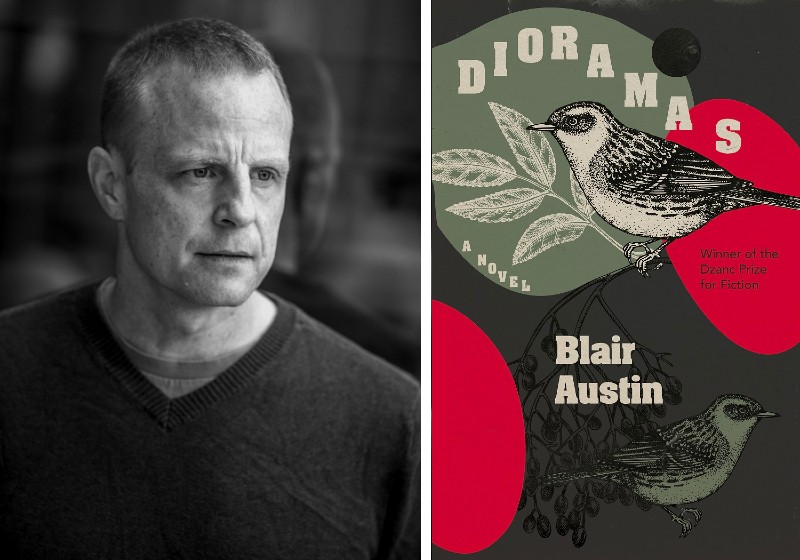

Lifelike Living: Blair Austin's inventive new book, "Dioramas," defies easy categorization

Blair Austin's Dioramas, which won the Dzanc Books Prize for Fiction, is described by the publisher as “part essay, part prose poem, part travel narrative.”

The author—an Ann Arbor native and University of Michigan MFA alum—describes dioramas to “view” through the eyes of the main character, Wiggins, whose stream-of-consciousness narration means that the reader must piece his world together as the book progresses.

Austin creates a semblance of beauty in the slow-growing shock of what is contained in the dioramas' preserved scenes.

Wiggins, a lecturer, is a scholar of dioramas and builds them, too, even in retirement. He studies the works of experts Michaux and Goll, both of whom made dioramas and contributed their theories about the art form to the field. Regarding Michaux, Wiggins reveals:

EMU professor Christine Hume faces “Everything I Never Wanted to Know” in her new book

“Do I even know one woman who hasn’t been subjected to male violence? Do you? Why doesn’t that admission stop us in our tracks?” asks EMU professor Christine Hume in her new essay collection, Everything I Never Wanted to Know.

Hume in turn does just that—she stops in her tracks to examine the violence and the imperfect structures meant to address it. She takes a critical lens to the ways that women’s bodies have been controlled through expressing productive outrage and through creating a mapping of this issue in our community. Her persistent questioning illuminates the injustices by compelling the reader to consider a response.

Take the National Sex Offender Registry: “Not a single man who has harassed or assaulted me or anyone I know is on that official list. How many men is that? How many men not on the registry does it take to make that registry itself an offense? How many men are we talking?” Hume accentuates the failings of a system that is supposed to contribute to safety. She goes on to scrutinize the laws that prevent offenders from living near a school or passing out Halloween candy, the design of the water tower in Ypsilanti, and a sexual assault case at Eastern Michigan University.

The essay “Icy Girls, Frigid Bitches, Frozen Dolls” looks at the implications of the once-popular Frozen Charlotte dolls in conjunction with a health issue that the author endures. Dolls in general are of interest, as Hume wonders, “What draws me to the doll is the vague but persistent sense of having lost my true and best self. A feeling of having once been more free, disciplined, attentive, athletic, daring, intelligent, and attractive.” The doll becomes a reflection of oneself:

Follow the Reindeer: Hanna Pylväinen's novel tracks missionaries and herders living on the Scandinavian tundra in 1851

How do you know when an action is a mistake or a choice?

This distinction is the question and crux of many turning points in The End of Drum-Time by U-M alum Hanna Pylväinen.

As character Risten Tomma reflects on her decision to marry Mikkol:

But was that all it was, then? You said a thing and then it all changed, you lived with another man now, someone else came into your lávvu and slept with you across the fire from your parents. There would be a new dog, and even their dogs would have to learn to get along.

Some changes are anticlimactic, while other changes are catastrophic.

The sweeping, well-paced novel is set in 1851 in the Scandinavian tundra with missionaries and reindeer herders both vying for their ways of life. Another one of the main characters, Willa, the daughter of the pastor Lars Levi Laestadius, faces numerous life-altering decisions over the course of the book. Early on "she was a kettle left at a gentle boil, and with her heat she did nothing more than make coffee or tea.” Yet, when she starts encountering Ivvár Rasti on her walks, a stronger wave begins to roil in her for him, despite the fact that he calls her “a good little báhpa nieida, good little church-girl.”

Willa steps deeper and deeper into an irreversible series of events in which:

Ice Capades & Identity: Caroline Huntoon’s “Skating on Mars” follows a nonbinary middle schooler trying to find their place in the world

In the new middle-grade novel Skating on Mars by Ypsilanti writer and educator Caroline Huntoon, Mars is a nonbinary figure skater who is not only navigating how to be who they are but also grieving their father and experiencing the tumult of middle school friendships.

One of Mars’ challenges is to figure out how to express themselves in different aspects of their life, from revealing their preferred name and pronouns to their mom and sister to dealing with critical peers. Even though skating has always been a refuge for them, one of their coaches pushes them to bring their own style to their skating program. After demonstrating, Dmitri clarifies his request, which Mars questions:

“See, that’s not you,” Dmitri says.

“What?” I ask.

“It was the same steps, but not what you did before. And not what you should do in your own program.”

“Okay…” I’m still not sure what he expects from me.

“You have to find yourself. And the rest will come.”

“Yeah,” I say, my voice flat and low. In my head, I’m screaming, JUST TELL ME WHAT TO DO! And somewhere else altogether, I feel this horrible uncertainty about what Dmitri is telling me to do. Find myself? I’m not lost. That’s not the problem. Not really.

This issue is one for which Mars must live their way into an answer. The book chronicles their journey in first-person narration by Mars, including their perspective on their sport, friends’ betrayals, a first crush, and emotional processing.

Mars’ competitive nature sets the scene for a showdown with another skater and for pushing the gender boundaries on the ice. Whether they can manage the pressure, shift their family and friend’s understanding of who they are, and continue doing what they love become ongoing questions through the book. One thing is clear: Mars cannot chart their own path solely by themself.

AADL’s Downtown Library is hosting Huntoon for a reading, Q&A, and signing Thursday, June 15, at 2 pm.

I caught up with Huntoon for an interview.

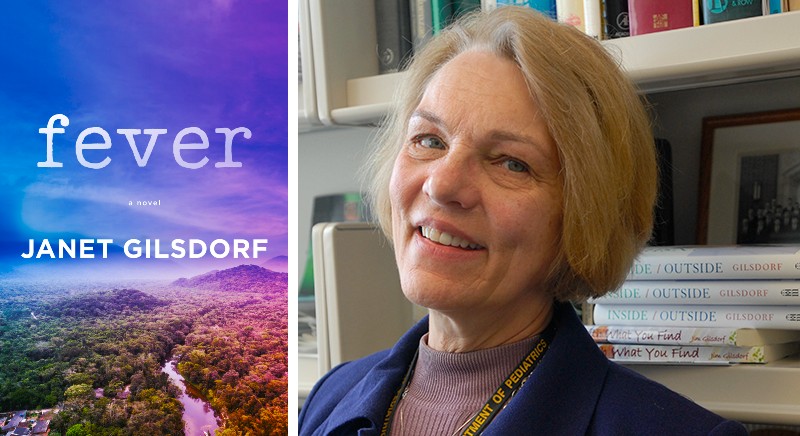

Dr. Janet Gilsdorf's novel "Fever" charts a mysterious illness and a researcher's race to discover the bacteria causing it

On a getaway with a colleague to visit family in Brazil, Dr. Sidonie Royal instead finds herself in a race to save children falling ill with a mysterious disease—and she experiences grief when they do not make it. Janet Gilsdorf's novel Fever tracks Sid’s subsequent research attempts back in Michigan to find out what is causing the deaths.

As a professor emerita of epidemiology and pediatrics at the University of Michigan, Gilsdorf is the right person to write a novel on this topic. Her work involves studying pathogenic factors, molecular genetics, and the epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae, a bacterium that causes invasive and respiratory infections in children and adults. It is this bacterium that Sid, the character in her novel, is trying to understand.

Many hurdles appear along the way for Sid. One problem consists of her belligerent lab mate, Eliot, who always seems ready with criticism. At one point, he informs Sid:

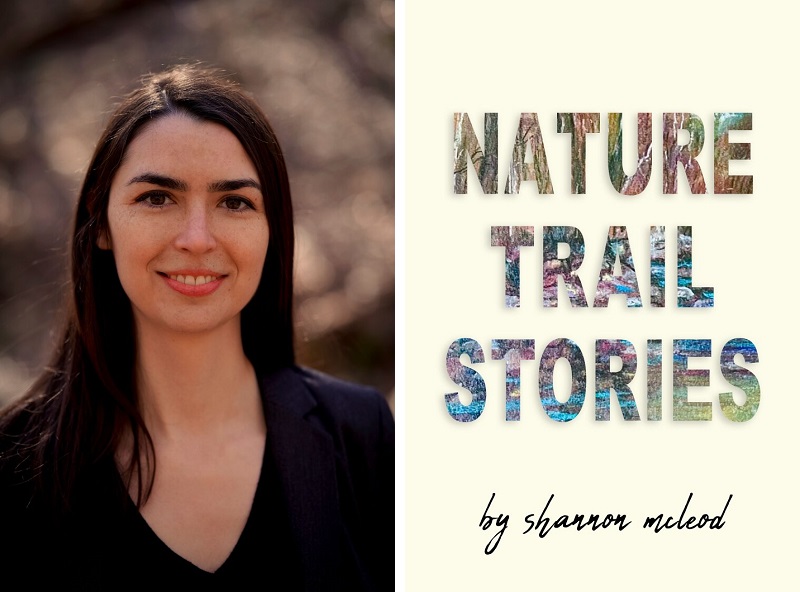

Shannon McLeod’s Short Story Collection “Nature Trail Stories” Provides Natural Spaces for People to Reflect and Integrate Their Past and Present Selves

Via sharp observations and attempts at connection, the characters in Shannon McLeod’s Nature Trail Stories offer insights on their surroundings and the people around them. As one woman reflects, “Any place can be scenic, depending upon the scenes in your head.” This mindset could be expanded to all the short stories in the collection, as they reveal the world through the characters’ varied outlooks, from an art gallery employee awaiting the next person to walk in to a woman coping with heartbreak.

In the same story from which the above quote originated, titled “Human Song,” the narrator and their boyfriend receive advice to go see the snails and sing to them to lure them out of their shells. At the beach:

I sing George Michael, then Spice Girls, then the Beatles.

“If they’re not coming out for Ringo, there’s nothing that’ll do it,” says Caleb. I’ve begun to feel this way about him, too. That nothing I can possibly do will bring him back to me.

Maybe the snails are more accessible than fellow humans. Nature becomes an antidote to the failings of relationships and to the desire for a bond.

The loneliness and longing that envelop these characters even as they engage with other people—friends, strangers, coworkers, family members, and significant others—thread throughout the collection and are almost inextricable from the dialogue and settings. The story, “After Leaving,” dives into the grim, though in this case necessary, moments following a breakup in which memories flash through the narrator’s mind wherever she goes. While seeking something for dinner, she observes that:

Downtown, the trees lining the streets are turning orange. There’s a sweet scent of decay in the air. I’ve always liked autumn best. He used to say it’s because I’m a melancholy woman. The same reason I find sad songs the most beautiful.

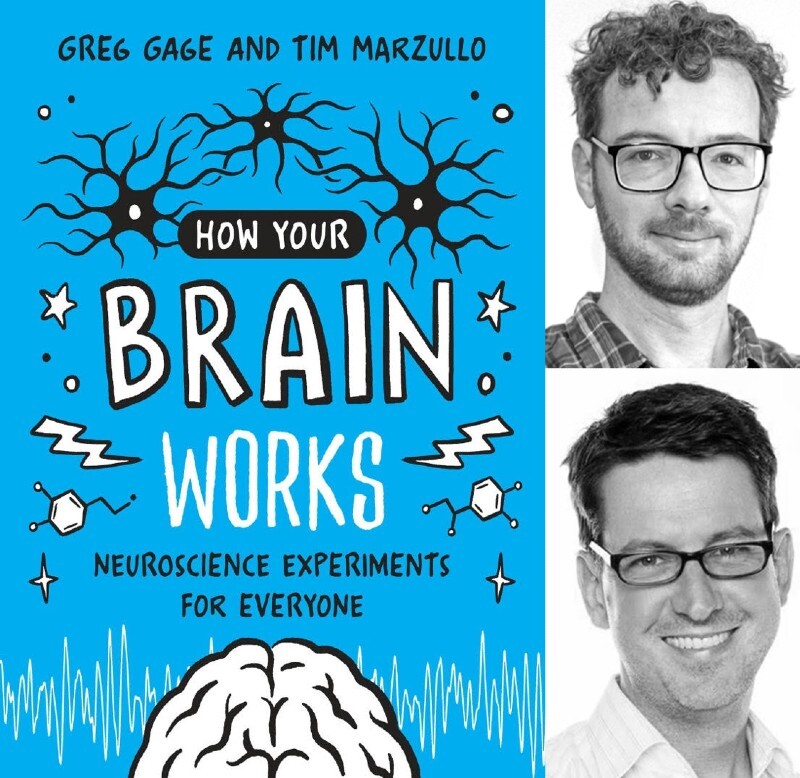

BACKYARD BRAINS' GREG GAGE AND TIM MARZULLO HELP PEOPLE EXPLORE NEUROSCIENCE IN THEIR NEW BOOK, "How Your Brain Works"

Have you ever wondered how sleep can improve memory? Or considered how your eyes perceive color? It turns out that you do not have to be a degreed scientist or even work in a lab to find out!

These questions all pertain to neuroscience, and it is possible to research them yourself by conducting the experiments in neuroscientists Greg Gage and Tim Marzullo’s new book, How Your Brain Works. Gage and Marzullo, the founders of Backyard Brains in Ann Arbor, make neuroscience available to everyone via more than 45 at-home tests outlined in their manual. The chapters keep the reader on the edge of their seat with the questions that the authors ask and the methods through which they answer them. As the two neuroscientists write, “Scientific discoveries can happen anywhere.” Plus, it is not only science – Gage and Marzullo offer humor alongside the science via illustrative drawings.

Neuroscience has long been an expensive endeavor, but tools that appeared in the early 2000s changed the landscape and brought neuroscience out of institutions and into anyone’s hands, Gage and Marzullo write. The premise of How Your Brain Works hinges on these technologies:

Stephanie Heit's New Hybrid Memoir Poem "Psych Murders" Examines Shock Treatment, The Aftermath, and How Time and Memory Move in Unexpected Ways

What do you do when the brain “acts more colander than container?”

Poet Stephanie Heit tests out an answer: “Strengthen your faith in electricity.” Her hybrid memoir poem, Psych Murders, reports on the decision to experience and recover from electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) as a treatment for bipolar disorder. Psych Murders contains a number of sections, often titled with questions such as “What brings you pleasure?” and “Are you safe?”

This journey with shock therapy and other attempted remedies takes the poet to a point where:

…you forget

How to swim.

Forget

your tokens.

Lose any sense

of direction.

This path also later reaches a place where, “Hope became a location.” The poet expresses some bitterness that, “I thought they’d figure out the code. No lack of rigor. But my body didn’t respond the way the data predicted.” Still, the side effects like memory loss and frustrations do not fully define the process for Heit. Instead, Heit concludes with the poem, “Testament,” which consists of a series of “I am” statements that embrace all parts of her identity.

Shortly after the start of the book, the Murderer appears, often described in third person, but always menacing and forming his own character, as the poet observes, “…I’m not alone. I have Murderer stalking my every move.” In a distressful twist in the poem, “The Murderer: Primetime,” he gets a chance to speak and shares his goal to reach her because he states of the poet that, “She haunts me—the one who slow danced in my grip. I’ll wait.” Despite his persistence, the Murderer’s interest in suicide nevertheless does not come to fruition, a victory for the poet and us readers.

Instead, Heit describes learning to live with the circumstances. The poem, “Chronic,” shows a begrudging acceptance that:

Chronic sounds like forever. Persistent forever. With a twang to the way the “ic” sticks in the throat. Almost guttural. Starts out ok. Chron, like chronological, that domino effect, out of control falling because gravity exists. But the ending turns. I am stuck with Chronic the rest of my life. Better than Terminal unless it refers to airports. Though at least with Terminal there is beginning, middle, end. Chronic is middle with no way out.

The poet shows us how, on the one hand, Chronic comes with its downsides, but on the other hand, Chronic means being alive.

Heit is a queer disabled poet, dancer, teacher, and codirector of Turtle Disco, a somatic writing space, based in Ypsilanti. We spoke to Heit about her writing, teaching, latest book, and next project.

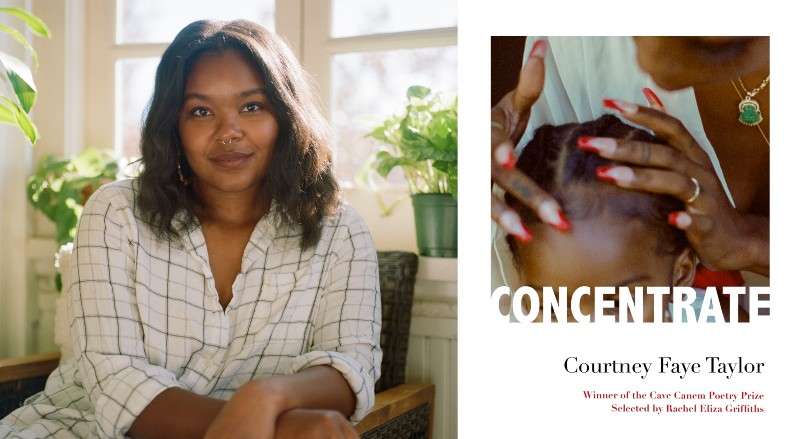

Courtney Faye Taylor explores racial injustices and the killing of Latasha Harlins in her debut poetry collection

Poetry becomes both memorial and voice in Courtney Faye Taylor's first book, Concentrate, winner of the Cave Canem Poetry Prize. The University of Michigan alum's poems honor, research, bristle, and circle back to the life and killing of Latasha Harlins, a Black girl gunned down by a Korean store owner, Soon Ja Du, in Los Angeles.

“In any black sentence, you’d love nothing more than to had made no mistake.” The opening prose poem that ends with this sentence mourns and fortifies Black womanhood. As Aunt Notrie says in the next poem, “The Talk,” it “Ain’t about trying, it’s about doing.” These lines do not let injustices lie but instead, “The poet wades into an uneasy ocean of interrogations that do not permit her any distance from what she has witnessed her entire life,” writes Rachel Eliza Griffiths in the introduction.

Some of the poems revisit history, like March 16, 1991, when Harlins lost her life. The poet starts another prose poem to outline how:

A timeline details a seriousness of events. As a diagram of occurrence, a timeline’s chief objective is to show how passed happenings caution and contaminate our contemporary sense of momentum. A professor may author timelines to teach what precedes and what follows genocide. On the overhead, Rwanda is a centipede with its head in Belgium and tail on stage of the ’05 Oscars.

The past remains with us as warning and blemish, and Taylor writes, “So I’m drawing a line.”

Other poems fashioned like Yelp reviews make stark the differences in treatment and standards among people. One of them gives two stars for “BLACK OWNED BUT HOURS WRONG ONLINE.” Such an offense garners a bolded complaint and strong consequence that “I will find a Korean store.” The loss of business for incorrect hours reinforces inequity and harshness.

Eventually, the poet goes to Los Angeles and visits the site of Harlin’s murder, “But there are no signs of murder, memorial, or resistance when I arrive. The ground is like any ground. Normalcy devastates. Stillness lies to me about history.” Taylor’s poems teach us that what is not visible is still present.

Early on, Aunt Notrie defines the word "concentrate" as “A strong, hard focus.” Taylor takes on that focus to scrutinize history through the poems. Later, Concentrate is a call to action, as in “Concentrate. We have decisions to make. Fire is that decision to make.” The word “we” leaves no one out. It is all of us who have responsibility.

Taylor is a writer and visual artist who earned her MFA from the University of Michigan, where she won a Hopwood Prize in Poetry. We spoke about Taylor's time in Ann Arbor, her poetry, and Concentrate.